Section 2. Emergency Services Available to Pilots

6-2-1. Radar Service for VFR Aircraft in Difficulty

- Radar equipped ATC facilities can provide radar assistance and navigation service (vectors) to VFR aircraft in difficulty when the pilot can talk with the controller, and the aircraft is within radar coverage. Pilots should clearly understand that authorization to proceed in accordance with such radar navigational assistance does not constitute authorization for the pilot to violate CFRs. In effect, assistance is provided on the basis that navigational guidance information is advisory in nature, and the responsibility for flying the aircraft safely remains with the pilot.

- Experience has shown that many pilots who are not qualified for instrument flight cannot maintain control of their aircraft when they encounter clouds or other reduced visibility conditions. In many cases, the controller will not know whether flight into instrument conditions will result from ATC instructions. To avoid possible hazards resulting from being vectored into IFR conditions, a pilot in difficulty should keep the controller advised of the current weather conditions being encountered and the weather along the course ahead and observe the following:

- If a course of action is available which will permit flight and a safe landing in VFR weather conditions, noninstrument rated pilots should choose the VFR condition rather than requesting a vector or approach that will take them into IFR weather conditions; or

- If continued flight in VFR conditions is not possible, the noninstrument rated pilot should so advise the controller and indicating the lack of an instrument rating, declare a distress condition; or

- If the pilot is instrument rated and current, and the aircraft is instrument equipped, the pilot should so indicate by requesting an IFR flight clearance. Assistance will then be provided on the basis that the aircraft can operate safely in IFR weather conditions.

6-2-2. Transponder Emergency Operation

- When a distress or urgency condition is encountered, the pilot of an aircraft with a coded radar beacon transponder, who desires to alert a ground radar facility, should squawk Mode 3/A, Code 7700/Emergency and Mode C altitude reporting and then immediately establish communications with the ATC facility.

- Radar facilities are equipped so that Code 7700 normally triggers an alarm or special indicator at all control positions. Pilots should understand that they might not be within a radar coverage area. Therefore, they should continue squawking Code 7700 and establish radio communications as soon as possible.

6-2-3. Intercept and Escort

- The concept of airborne intercept and escort is based on the Search and Rescue (SAR) aircraft establishing visual and/or electronic contact with an aircraft in difficulty, providing in‐flight assistance, and escorting it to a safe landing. If bailout, crash landing or ditching becomes necessary, SAR operations can be conducted without delay. For most incidents, particularly those occurring at night and/or during instrument flight conditions, the availability of intercept and escort services will depend on the proximity of SAR units with suitable aircraft on alert for immediate dispatch. In limited circumstances, other aircraft flying in the vicinity of an aircraft in difficulty can provide these services.

- If specifically requested by a pilot in difficulty or if a distress condition is declared, SAR coordinators will take steps to intercept and escort an aircraft. Steps may be initiated for intercept and escort if an urgency condition is declared and unusual circumstances make such action advisable.

- It is the pilot's prerogative to refuse intercept and escort services. Escort services will normally be provided to the nearest adequate airport. Should the pilot receiving escort services continue onto another location after reaching a safe airport, or decide not to divert to the nearest safe airport, the escort aircraft is not obligated to continue and further escort is discretionary. The decision will depend on the circumstances of the individual incident.

6-2-4. Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT)

- General.

- ELTs are required for most General Aviation airplanes.

- ELTs of various types were developed as a means of locating downed aircraft. These electronic, battery operated transmitters operate on one of three frequencies. These operating frequencies are 121.5 MHz, 243.0 MHz, and the newer 406 MHz. ELTs operating on 121.5 MHz and 243.0 MHz are analog devices. The newer 406 MHz ELT is a digital transmitter that can be encoded with the owner's contact information or aircraft data. The latest 406 MHz ELT models can also be encoded with the aircraft's position data which can help SAR forces locate the aircraft much more quickly after a crash. The 406 MHz ELTs also transmits a stronger signal when activated than the older 121.5 MHz ELTs.

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) requires 406 MHz ELTs be registered with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as outlined in the ELTs documentation. The FAA's 406 MHz ELT Technical Standard Order (TSO) TSO-C126 also requires that each 406 MHz ELT be registered with NOAA. The reason is NOAA maintains the owner registration database for U.S. registered 406 MHz alerting devices, which includes ELTs. NOAA also operates the United States' portion of the Cospas-Sarsat satellite distress alerting system designed to detect activated 406 MHz ELTs and other distress alerting devices.

- As of 2009, the Cospas-Sarsat system terminated monitoring and reception of the 121.5 MHz and 243.0 MHz frequencies. What this means for pilots is that those aircraft with only 121.5 MHz or 243.0 MHz ELTs onboard will have to depend upon either a nearby air traffic control facility receiving the alert signal or an overflying aircraft monitoring 121.5 MHz or 243.0 MHz detecting the alert and advising ATC.

- In the event that a properly registered 406 MHz ELT activates, the Cospas-Sarsat satellite system can decode the owner's information and provide that data to the appropriate search and rescue (SAR) center. In the United States, NOAA provides the alert data to the appropriate U.S. Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (RCC) or U.S. Coast Guard Rescue Coordination Center. That RCC can then telephone or contact the owner to verify the status of the aircraft. If the aircraft is safely secured in a hangar, a costly ground or airborne search is avoided. In the case of an inadvertent 406 MHz ELT activation, the owner can deactivate the 406 MHz ELT. If the 406 MHz ELT equipped aircraft is being flown, the RCC can quickly activate a search. 406 MHz ELTs permit the Cospas-Sarsat satellite system to narrow the search area to a more confined area compared to that of a 121.5 MHz or 243.0 MHz ELT. 406 MHz ELTs also include a low-power 121.5 MHz homing transmitter to aid searchers in finding the aircraft in the terminal search phase.

- Each analog ELT emits a distinctive downward swept audio tone on 121.5 MHz and 243.0 MHz.

- If “armed” and when subject to crash-generated forces, ELTs are designed to automatically activate and continuously emit their respective signals, analog or digital. The transmitters will operate continuously for at least 48 hours over a wide temperature range. A properly installed, maintained, and functioning ELT can expedite search and rescue operations and save lives if it survives the crash and is activated.

- Pilots and their passengers should know how to activate the aircraft's ELT if manual activation is required. They should also be able to verify the aircraft's ELT is functioning and transmitting an alert after a crash or manual activation.

- Because of the large number of 121.5 MHz ELT false alerts and the lack of a quick means of verifying the actual status of an activated 121.5 MHz or 243.0 MHz analog ELT through an owner registration database, U.S. SAR forces do not respond as quickly to initial 121.5/243.0 MHz ELT alerts as the SAR forces do to 406 MHz ELT alerts. Compared to the almost instantaneous detection of a 406 MHz ELT, SAR forces' normal practice is to wait for confirmation of an overdue aircraft or similar notification. In some cases, this confirmation process can take hours. SAR forces can initiate a response to 406 MHz alerts in minutes compared to the potential delay of hours for a 121.5/243.0 MHz ELT. Therefore, due to the obvious advantages of 406 MHz beacons and the significant disadvantages to the older 121.5/243.0 MHz beacons, and considering that the International Cospas-Sarsat Program stopped the monitoring of 121.5/243.0 MHz by satellites on February 1, 2009, all aircraft owners/operators are highly encouraged by both NOAA and the FAA to consider making the switch to a digital 406 MHz ELT beacon. Further, for non-aircraft owner pilots, check the ELT installed in the aircraft you are flying, and as appropriate, obtain a personal locator beacon transmitting on 406 MHz.

- Testing.

- ELTs should be tested in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, preferably in a shielded or screened room or specially designed test container to prevent the broadcast of signals which could trigger a false alert.

- When this cannot be done, aircraft operational testing is authorized as follows:

- Analog 121.5/243 MHz ELTs should only be tested during the first 5 minutes after any hour. If operational tests must be made outside of this period, they should be coordinated with the nearest FAA Control Tower. Tests should be no longer than three audible sweeps. If the antenna is removable, a dummy load should be substituted during test procedures.

- Digital 406 MHz ELTs should only be tested in accordance with the unit's manufacturer's instructions.

- Airborne tests are not authorized.

- False Alarms.

- Caution should be exercised to prevent the inadvertent activation of ELTs in the air or while they are being handled on the ground. Accidental or unauthorized activation will generate an emergency signal that cannot be distinguished from the real thing, leading to expensive and frustrating searches. A false ELT signal could also interfere with genuine emergency transmissions and hinder or prevent the timely location of crash sites. Frequent false alarms could also result in complacency and decrease the vigorous reaction that must be attached to all ELT signals.

- Numerous cases of inadvertent activation have occurred as a result of aerobatics, hard landings, movement by ground crews and aircraft maintenance. These false alarms can be minimized by monitoring 121.5 MHz and/or 243.0 MHz as follows:

- In flight when a receiver is available.

- Before engine shut down at the end of each flight.

- When the ELT is handled during installation or maintenance.

- When maintenance is being performed near the ELT.

- When a ground crew moves the aircraft.

- If an ELT signal is heard, turn off the aircraft's ELT to determine if it is transmitting. If it has been activated, maintenance might be required before the unit is returned to the “ARMED” position. You should contact the nearest Air Traffic facility and notify it of the inadvertent activation.

- Inflight Monitoring and Reporting.

- Pilots are encouraged to monitor 121.5 MHz and/or 243.0 MHz while inflight to assist in identifying possible emergency ELT transmissions. On receiving a signal, report the following information to the nearest air traffic facility:

- Your position at the time the signal was first heard.

- Your position at the time the signal was last heard.

- Your position at maximum signal strength.

- Your flight altitudes and frequency on which the emergency signal was heard: 121.5 MHz or 243.0 MHz. If possible, positions should be given relative to a navigation aid. If the aircraft has homing equipment, provide the bearing to the emergency signal with each reported position.

- Pilots are encouraged to monitor 121.5 MHz and/or 243.0 MHz while inflight to assist in identifying possible emergency ELT transmissions. On receiving a signal, report the following information to the nearest air traffic facility:

6-2-5. FAA K-9 Explosives Detection Team Program

- The FAA's Office of Civil Aviation Security Operations manages the FAA K-9 Explosives Detection Team Program which was established in 1972. Through a unique agreement with law enforcement agencies and airport authorities, the FAA has strategically placed FAA-certified K-9 teams (a team is one handler and one dog) at airports throughout the country. If a bomb threat is received while an aircraft is in flight, the aircraft can be directed to an airport with this capability. The FAA provides initial and refresher training for all handlers, provides single purpose explosive detector dogs, and requires that each team is annually evaluated in five areas for FAA certification: aircraft (widebody and narrowbody), vehicles, terminal, freight (cargo), and luggage. If you desire this service, notify your company or an FAA air traffic control facility.

- The following list shows the locations of current FAA K-9 teams:

TBL 6-2-1

FAA Sponsored Explosives Detection Dog/Handler Team LocationsAirport Symbol

Location

ATL

Atlanta, Georgia

BHM

Birmingham, Alabama

BOS

Boston, Massachusetts

BUF

Buffalo, New York

CLT

Charlotte, North Carolina

ORD

Chicago, Illinois

CVG

Cincinnati, Ohio

DFW

Dallas, Texas

DEN

Denver, Colorado

DTW

Detroit, Michigan

IAH

Houston, Texas

JAX

Jacksonville, Florida

MCI

Kansas City, Missouri

LAX

Los Angeles, California

MEM

Memphis, Tennessee

Airport Symbol

Location

MIA

Miami, Florida

MKE

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

MSY

New Orleans, Louisiana

MCO

Orlando, Florida

PHX

Phoenix, Arizona

PIT

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

PDX

Portland, Oregon

SLC

Salt Lake City, Utah

SFO

San Francisco, California

SJU

San Juan, Puerto Rico

SEA

Seattle, Washington

STL

St. Louis, Missouri

TUS

Tucson, Arizona

TUL

Tulsa, Oklahoma

- If due to weather or other considerations an aircraft with a suspected hidden explosive problem were to land or intended to land at an airport other than those listed in b above, it is recommended that they call the FAA's Washington Operations Center (telephone 202-267-3333, if appropriate) or have an air traffic facility with which you can communicate contact the above center requesting assistance.

6-2-6. Search and Rescue

- General. SAR is a lifesaving service provided through the combined efforts of the federal agencies signatory to the National SAR Plan, and the agencies responsible for SAR within each state. Operational resources are provided by the U.S. Coast Guard, DoD components, the Civil Air Patrol, the Coast Guard Auxiliary, state, county and local law enforcement and other public safety agencies, and private volunteer organizations. Services include search for missing aircraft, survival aid, rescue, and emergency medical help for the occupants after an accident site is located.

- National Search and Rescue Plan. By federal interagency agreement, the National Search and Rescue Plan provides for the effective use of all available facilities in all types of SAR missions. These facilities include aircraft, vessels, pararescue and ground rescue teams, and emergency radio fixing. Under the plan, the U.S. Coast Guard is responsible for the coordination of SAR in the Maritime Region, and the USAF is responsible in the Inland Region. To carry out these responsibilities, the Coast Guard and the Air Force have established Rescue Coordination Centers (RCCs) to direct SAR activities within their regions. For aircraft emergencies, distress, and urgency, information normally will be passed to the appropriate RCC through an ARTCC or FSS.

- Coast Guard Rescue Coordination Centers. (See TBL 6-2-2.)

TBL 6-2-2

Coast Guard Rescue Coordination CentersCoast Guard Rescue Coordination Centers

Alameda, CA

510-437-3701Miami, FL

305-415-6800Boston, MA

617-223-8555

New Orleans, LA

504-589-6225Cleveland, OH

216-902-6117Portsmouth, VA

757-398-6390Honolulu, HI

808-541-2500Seattle, WA

206-220-7001Juneau, AK

907-463-2000San Juan, PR

787-289-2042 - Air Force Rescue Coordination Centers. (See TBL 6-2-3 and TBL 6-2-4.)

TBL 6-2-3

Air Force Rescue Coordination Center

48 Contiguous StatesAir Force Rescue Coordination Center

Tyndall AFB, Florida

Phone

Commercial

850-283-5955

WATS

800-851-3051

DSN

523-5955

TBL 6-2-4

Air Command Rescue Coordination Center

AlaskaAlaskan Air Command Rescue

Coordination CenterElmendorf AFB, Alaska

Phone

Commercial

907-428-7230

800-420-7230

(outside Anchorage)DSN

317-551-7230

- Joint Rescue Coordination Center. (See TBL 6-2-5.)

TBL 6-2-5

Joint Rescue Coordination Center

HawaiiHonolulu Joint Rescue Coordination Center

HQ 14th CG District

HonoluluPhone

Commercial

808-541-2500

DSN

448-0301

- Emergency and Overdue Aircraft.

- ARTCCs and FSSs will alert the SAR system when information is received from any source that an aircraft is in difficulty, overdue, or missing.

- Radar facilities providing radar flight following or advisories consider the loss of radar and radios, without service termination notice, to be a possible emergency. Pilots receiving VFR services from radar facilities should be aware that SAR may be initiated under these circumstances.

- A filed flight plan is the most timely and effective indicator that an aircraft is overdue.Flight plan information is invaluable to SAR forces for search planning and executing search efforts.

- Prior to departure on every flight, local or otherwise, someone at the departure point should be advised of your destination and route of flight if other than direct. Search efforts are often wasted and rescue is often delayed because of pilots who thoughtlessly takeoff without telling anyone where they are going. File a flight plan for your safety.

- According to the National Search and Rescue Plan, “The life expectancy of an injured survivor decreases as much as 80 percent during the first 24 hours, while the chances of survival of uninjured survivors rapidly diminishes after the first 3 days.”

- An Air Force Review of 325 SAR missions conducted during a 23-month period revealed that “Time works against people who experience a distress but are not on a flight plan, since 36 hours normally pass before family concern initiates an (alert).”

- ARTCCs and FSSs will alert the SAR system when information is received from any source that an aircraft is in difficulty, overdue, or missing.

- VFR Search and Rescue Protection.

- To receive this valuable protection, file a VFR or DVFR Flight Plan with an FAA FSS. For maximum protection, file only to the point of first intended landing, and refile for each leg to final destination. When a lengthy flight plan is filed, with several stops en route and an ETE to final destination, a mishap could occur on any leg, and unless other information is received, it is probable that no one would start looking for you until 30 minutes after your ETA at your final destination.

- If you land at a location other than the intended destination, report the landing to the nearest FAA FSS and advise them of your original destination.

- If you land en route and are delayed more than 30 minutes, report this information to the nearest FSS and give them your original destination.

- If your ETE changes by 30 minutes or more, report a new ETA to the nearest FSS and give them your original destination. Remember that if you fail to respond within one‐half hour after your ETA at final destination, a search will be started to locate you.

- It is important that you close your flight plan IMMEDIATELY AFTER ARRIVAL AT YOUR FINAL DESTINATION WITH THE FSS DESIGNATED WHEN YOUR FLIGHT PLAN WAS FILED. The pilot is responsible for closure of a VFR or DVFR flight plan; they are not closed automatically. This will prevent needless search efforts.

- The rapidity of rescue on land or water will depend on how accurately your position may be determined. If a flight plan has been followed and your position is on course, rescue will be expedited.

- Survival Equipment.

- For flight over uninhabited land areas, it is wise to take and know how to use survival equipment for the type of climate and terrain.

- If a forced landing occurs at sea, chances for survival are governed by the degree of crew proficiency in emergency procedures and by the availability and effectiveness of water survival equipment.

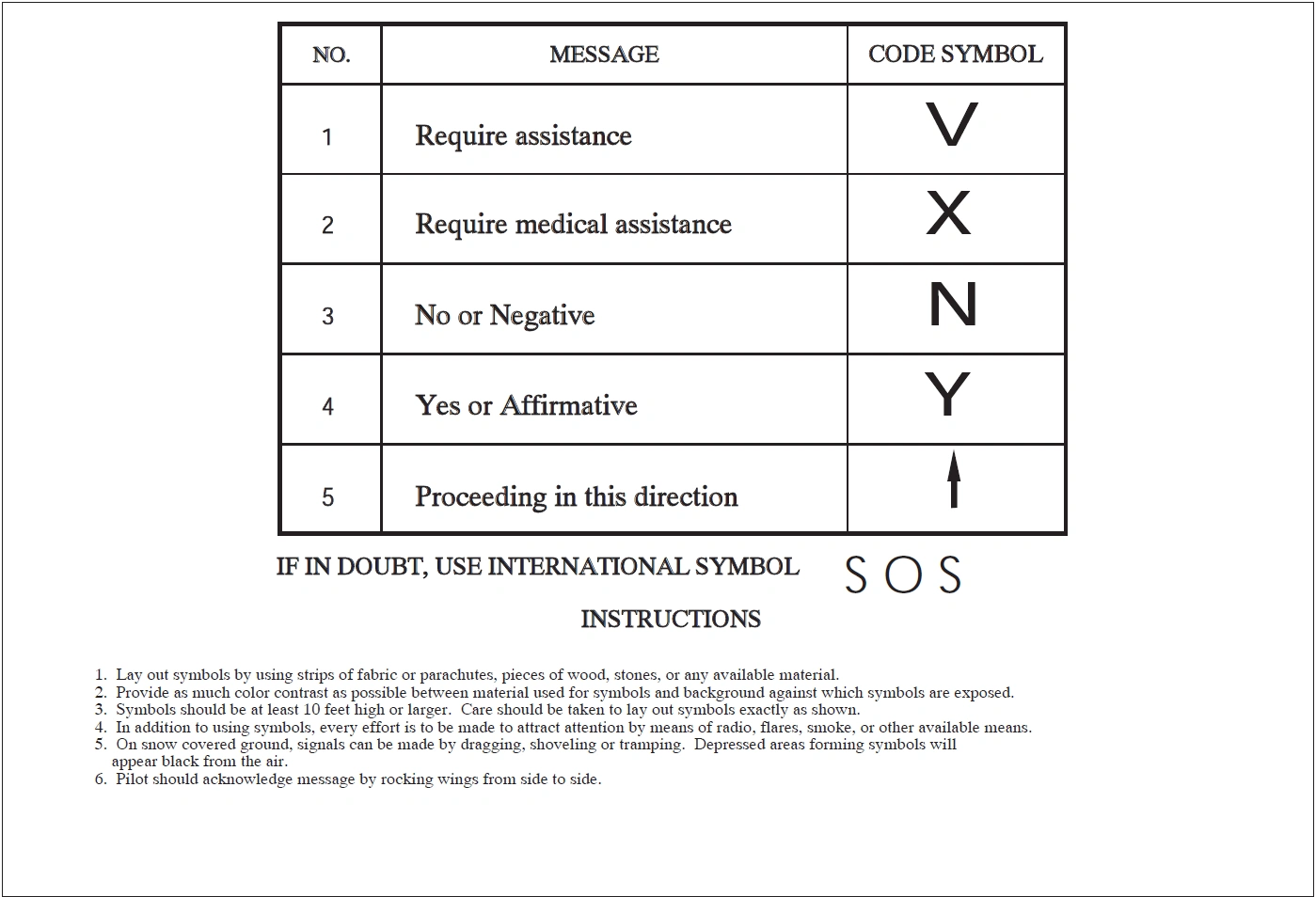

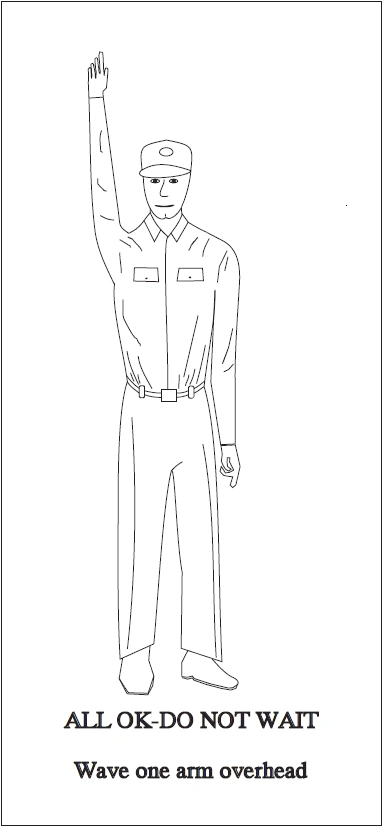

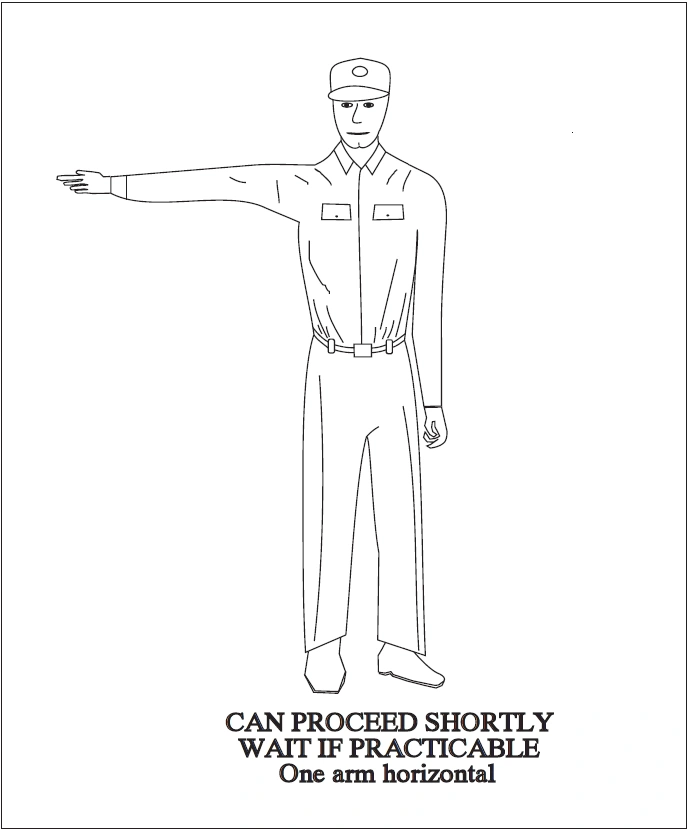

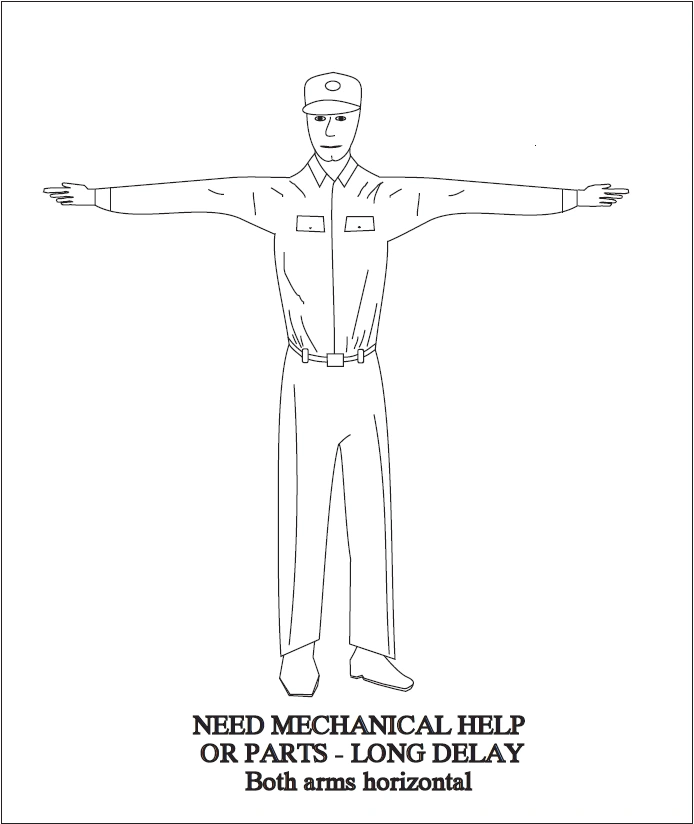

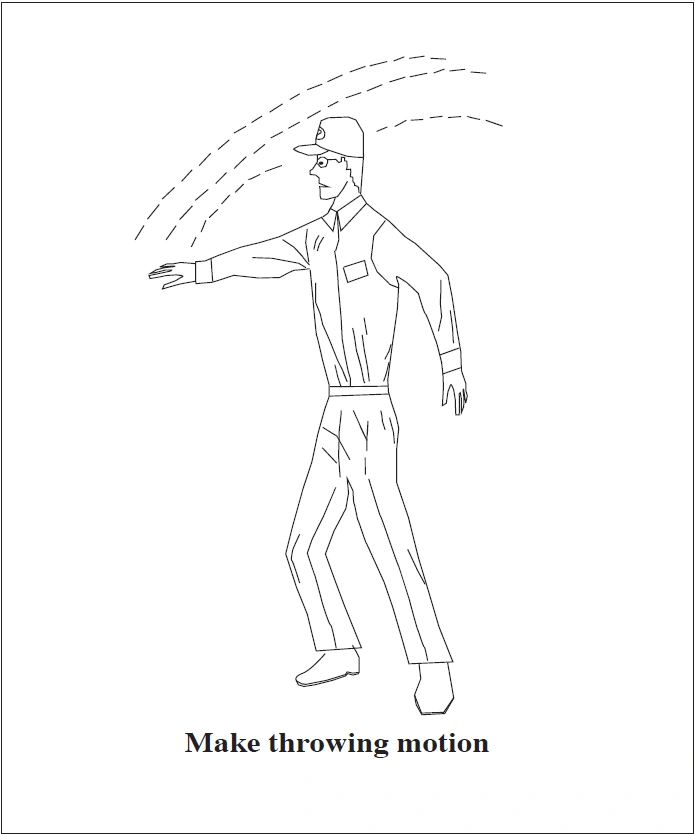

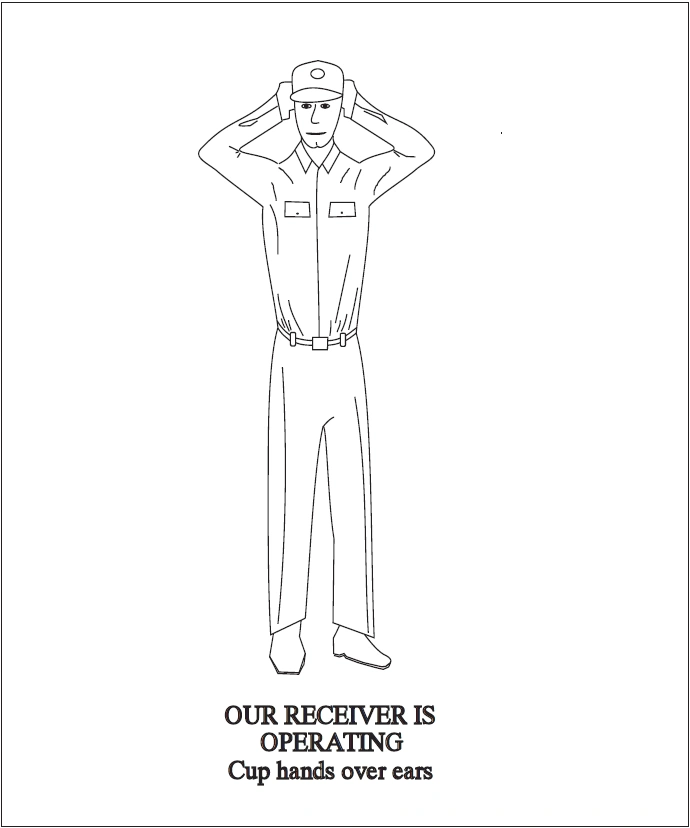

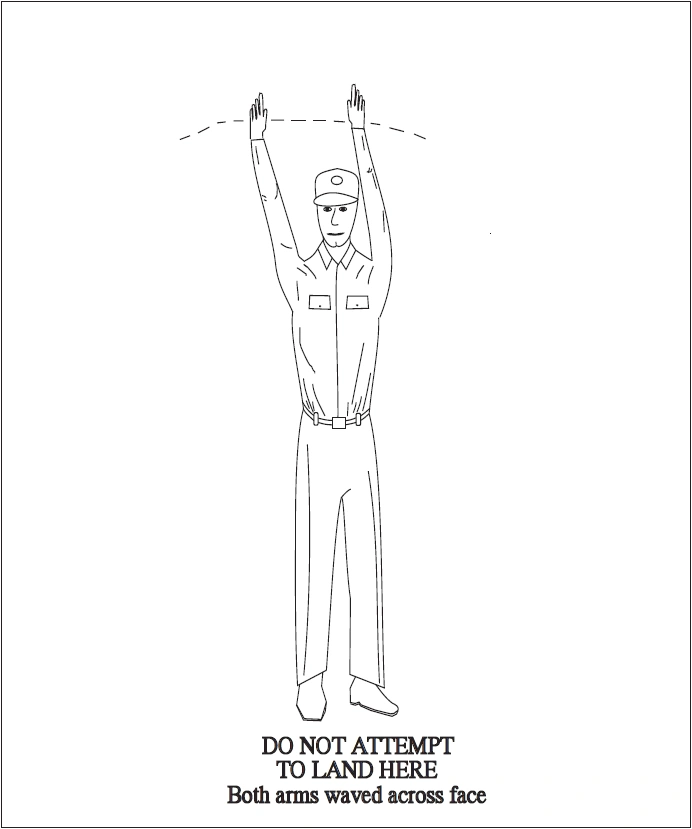

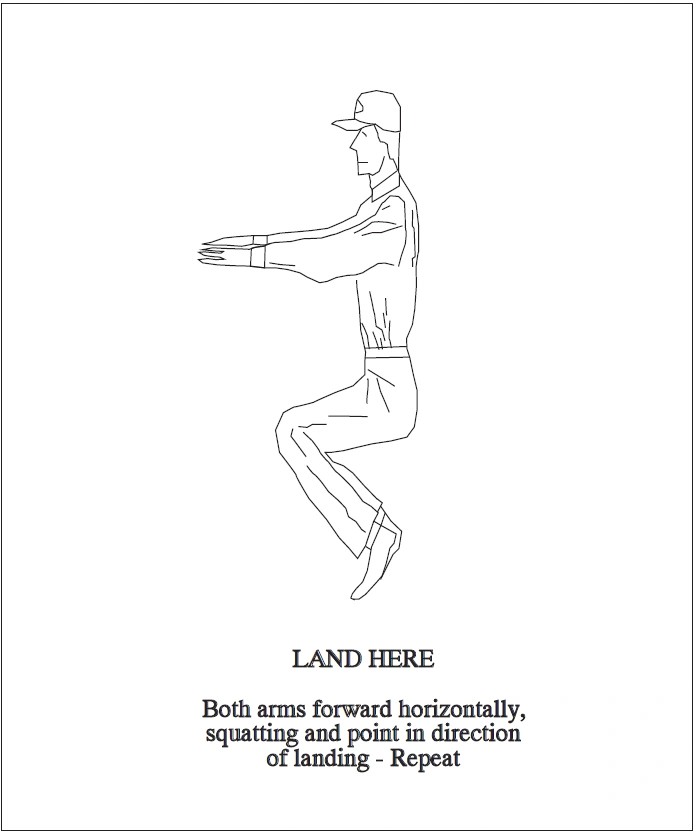

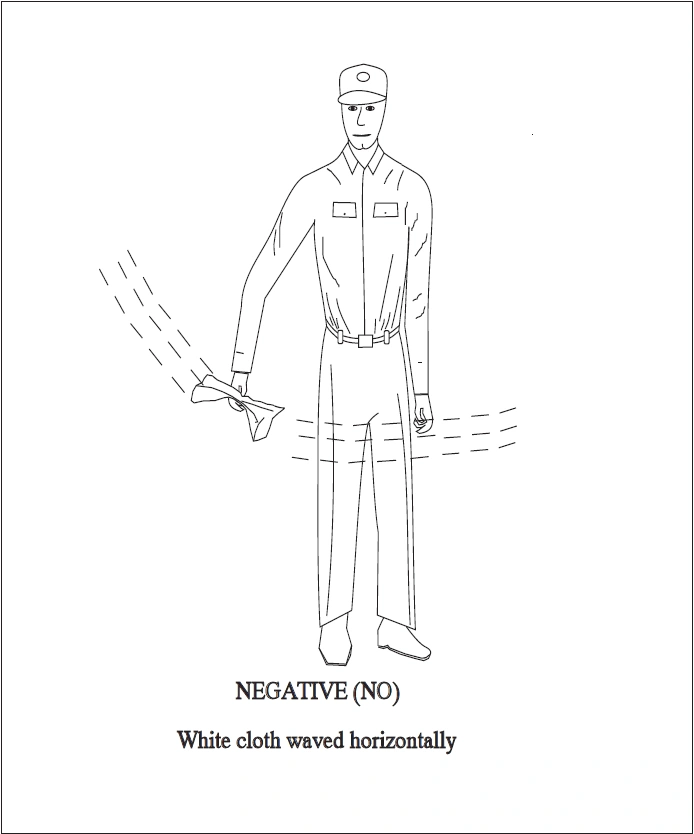

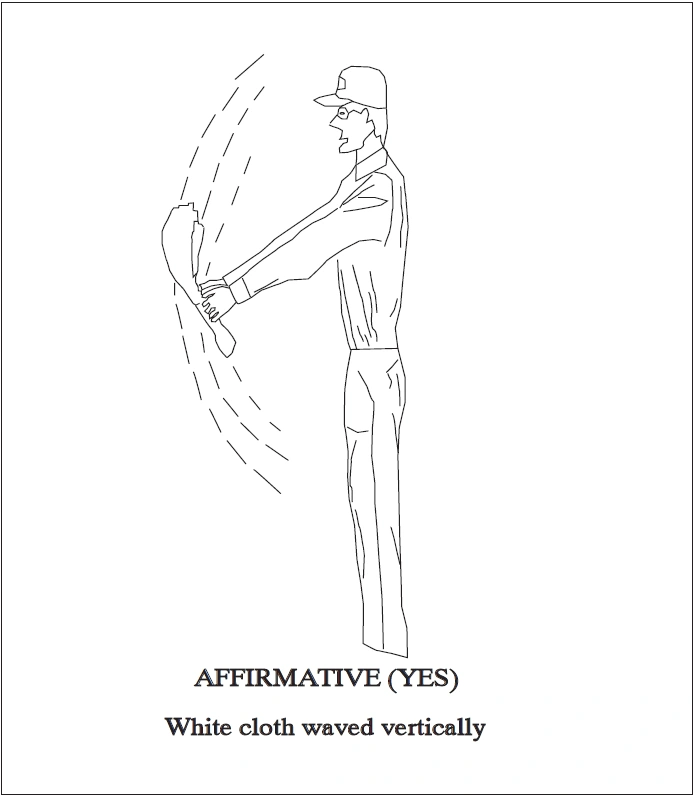

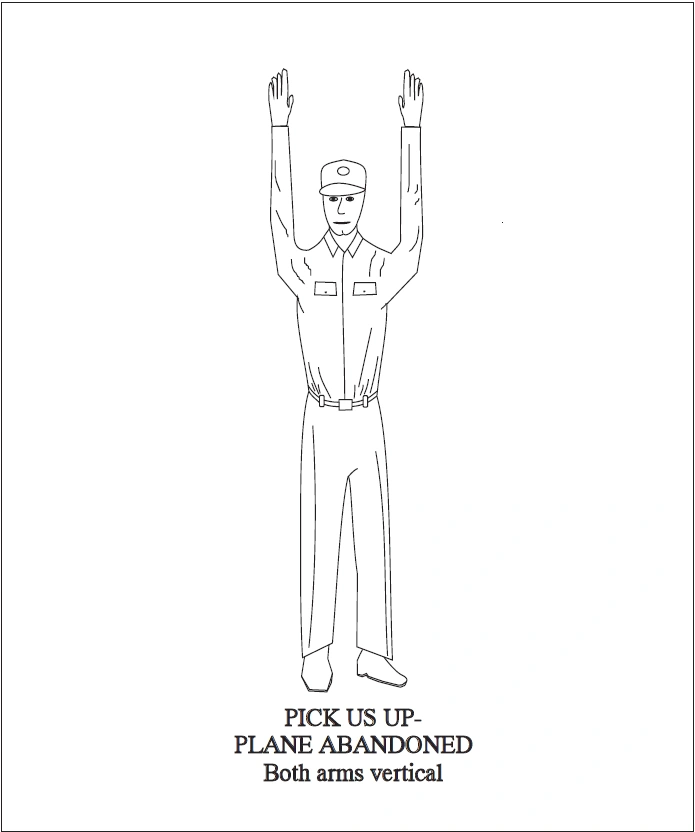

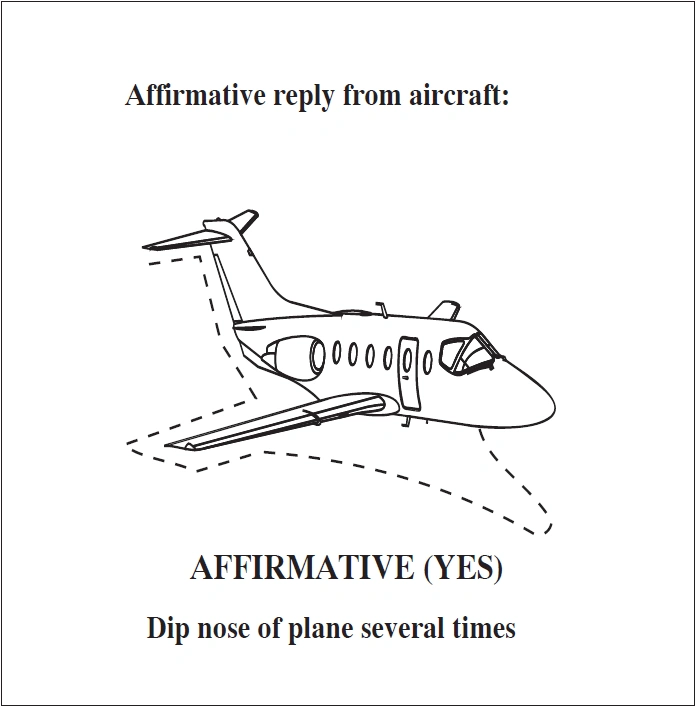

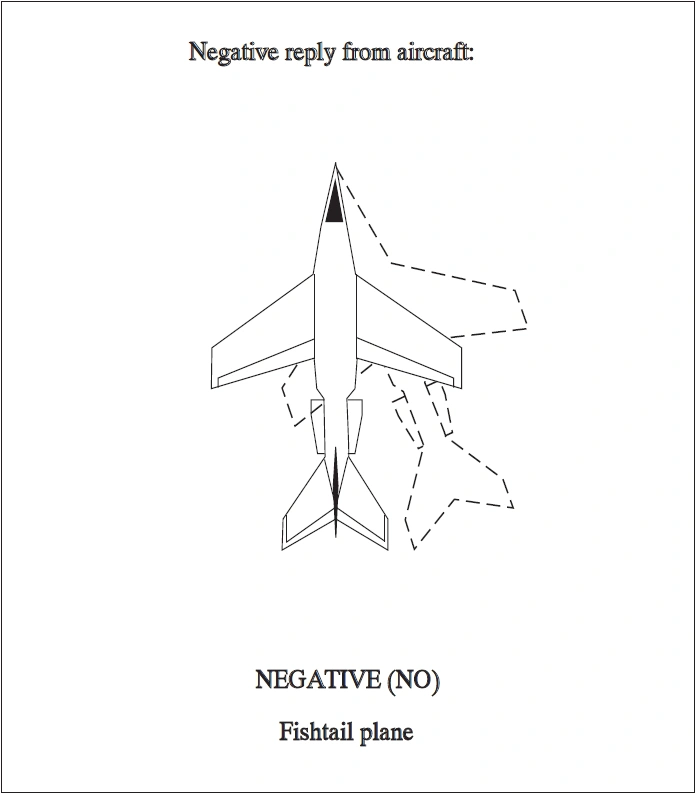

- Body Signal Illustrations.

- If you are forced down and are able to attract the attention of the pilot of a rescue airplane, the body signals illustrated on these pages can be used to transmit messages to the pilot circling over your location.

- Stand in the open when you make the signals.

- Be sure the background, as seen from the air, is not confusing.

- Go through the motions slowly and repeat each signal until you are positive that the pilot understands you.

- Observance of Downed Aircraft.

- Determine if crash is marked with a yellow cross; if so, the crash has already been reported and identified.

- If possible, determine type and number of aircraft and whether there is evidence of survivors.

- Fix the position of the crash as accurately as possible with reference to a navigational aid. If possible, provide geographic or physical description of the area to aid ground search parties.

- Transmit the information to the nearest FAA or other appropriate radio facility.

- If circumstances permit, orbit the scene to guide in other assisting units until their arrival or until you are relieved by another aircraft.

- Immediately after landing, make a complete report to the nearest FAA facility, or Air Force or Coast Guard Rescue Coordination Center. The report can be made by a long distance collect telephone call.

FIG 6-2-1

Ground-Air Visual Code for Use by Survivors

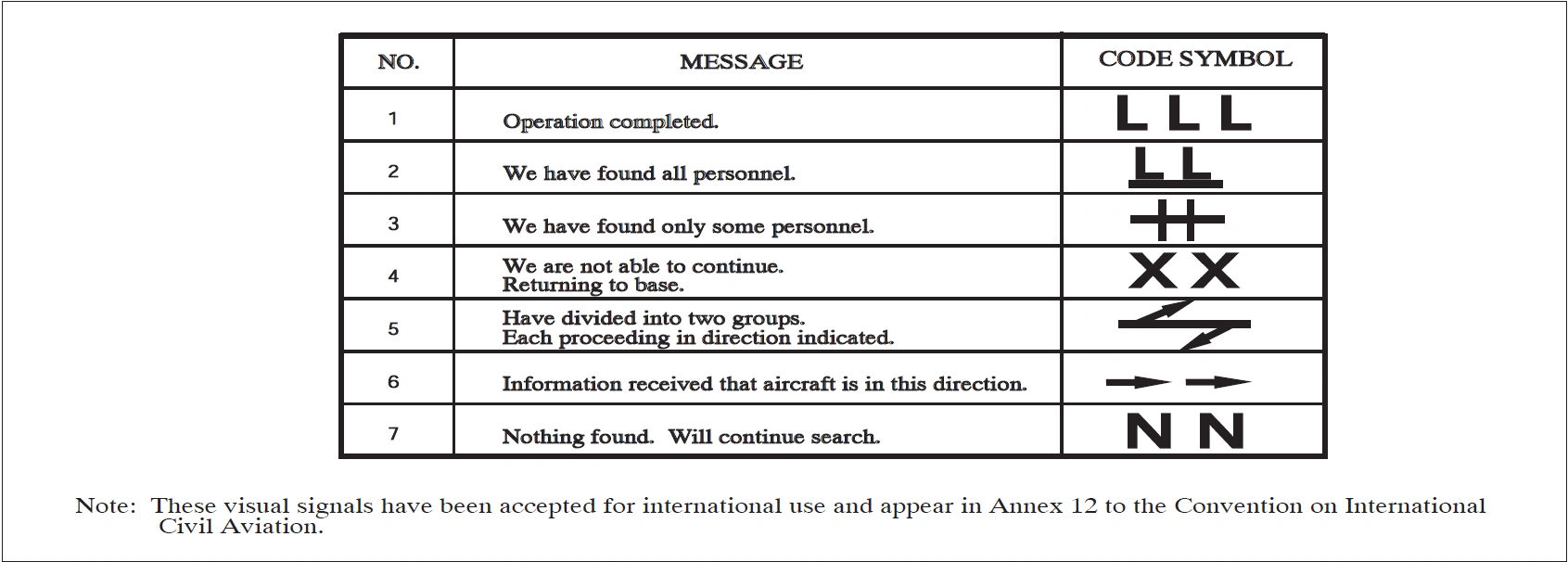

FIG 6-2-2

Ground-Air Visual Code for use by Ground Search Parties

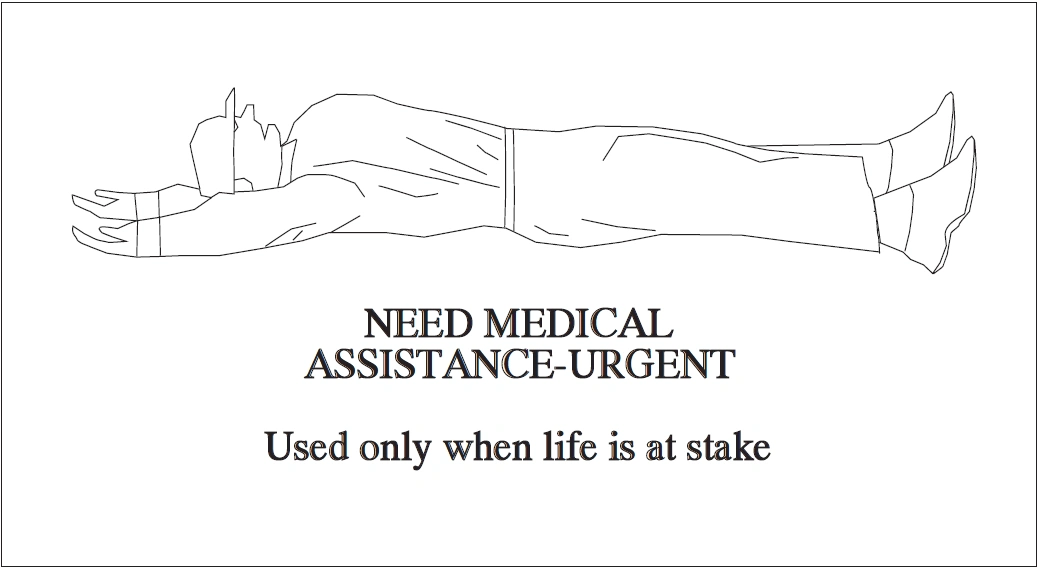

FIG 6-2-3

Urgent Medical Assistance

FIG 6-2-4

All OK

FIG 6-2-5

Short Delay

FIG 6-2-6

Long Delay

FIG 6-2-7

Drop Message

FIG 6-2-8

Receiver Operates

FIG 6-2-9

Do Not Land Here

FIG 6-2-10

Land Here

FIG 6-2-11

Negative (Ground)

FIG 6-2-12

Affirmative (Ground)

FIG 6-2-13

Pick Us Up

FIG 6-2-14

Affirmative (Aircraft)

FIG 6-2-15

Negative (Aircraft)

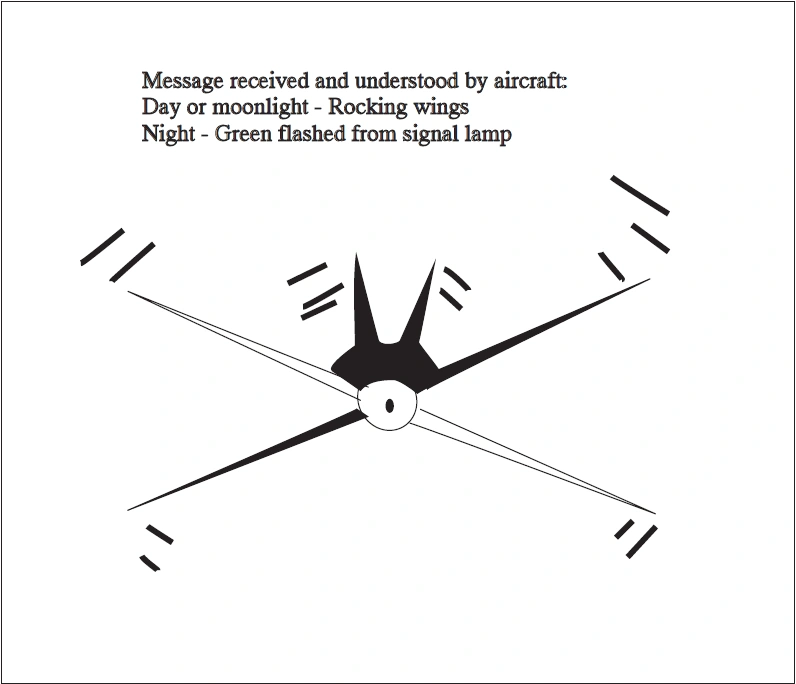

FIG 6-2-16

Message received and understood (Aircraft)

FIG 6-2-17

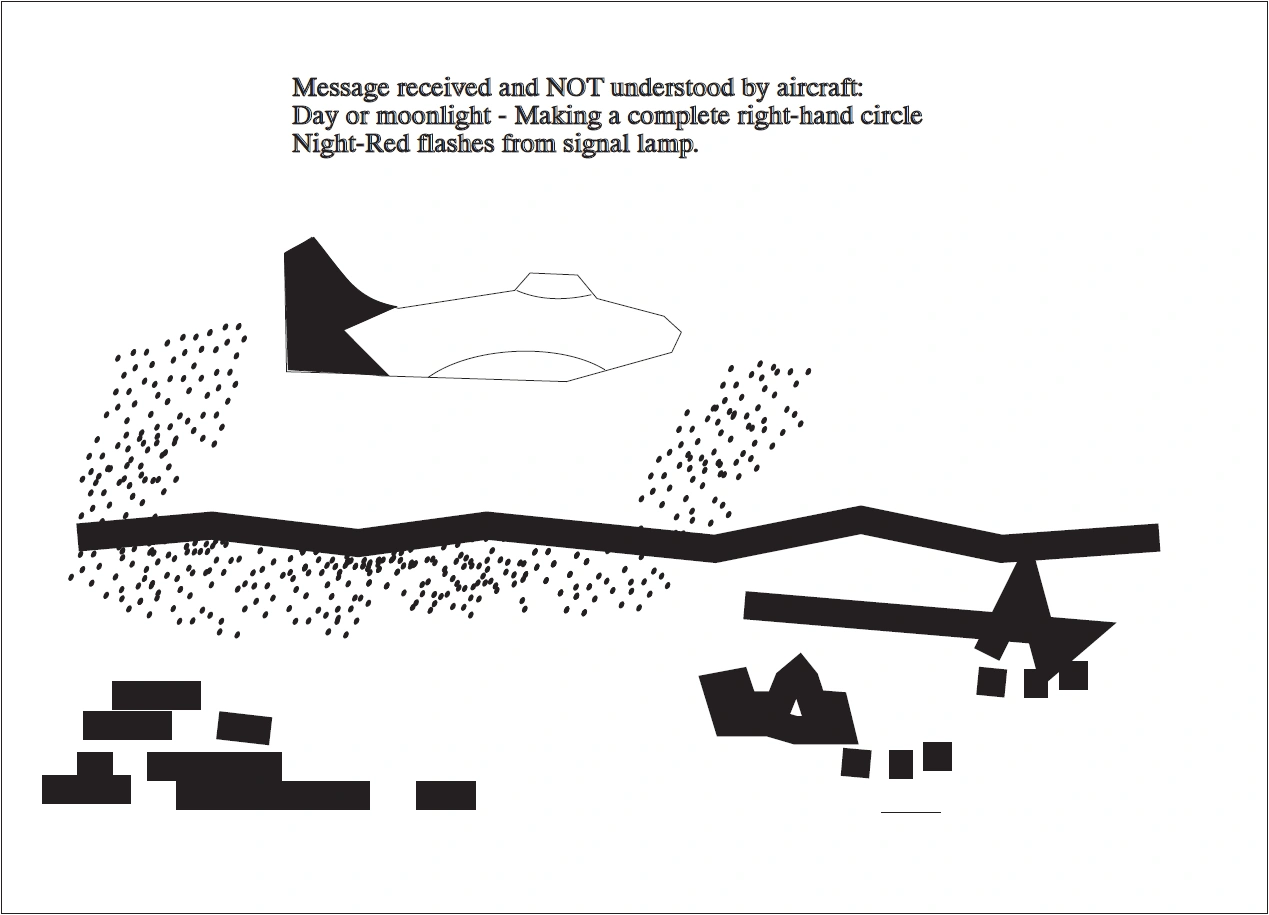

Message received and NOT understood (Aircraft)