ENR 4.1: Navigation Aids - En Route

1. Nondirectional Radio Beacon (NDB)

1.1 A low or medium frequency radio beacon transmits nondirectional signals whereby the pilot of an aircraft properly equipped can determine bearings and “home” on the station. These facilities normally operate in a frequency band of 190 to 535 kilohertz (kHz), according to ICAO Annex 10 the frequency range for NDBs is between 190 and 1750 kHz, and transmit a continuous carrier with either 400 or 1020 hertz (Hz) modulation. All radio beacons except the compass locators transmit a continuous three-letter identification in code except during voice transmissions.

1.2 When a radio beacon is used in conjunction with the Instrument Landing System markers, it is called a Compass Locator.

1.3 Voice transmissions are made on radio beacons unless the letter “W” (without voice) is included in the class designator (HW).

1.4 Radio beacons are subject to disturbances that may result in erroneous bearing information. Such disturbances result from such factors as lightning, precipitation, static, etc. At night radio beacons are vulnerable to interference from distant stations. Nearly all disturbances which affect the aircraft's Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) bearing also affect the facility's identification. Noisy identification usually occurs when the ADF needle is erratic; voice, music, or erroneous identification will usually be heard when a steady false bearing is being displayed. Since ADF receivers do not have a “FLAG” to warn the pilot when erroneous bearing information is being displayed, the pilot should continuously monitor the NDB's identification.

2. VHF Omni-directional Range (VOR)

2.1 VORs operate within the 108.0 - 117.95 MHz frequency band and have a power output necessary to provide coverage within their assigned operational service volume. They are subject to line-of-sight restrictions, and range varies proportionally to the altitude of the receiving equipment.

2.2 Most VORs are equipped for voice transmission on the VOR frequency. VORs without voice capability are indicated by the letter “W” (without voice) included in the class designator (VORW).

2.3 The effectiveness of the VOR depends upon proper use and adjustment of both ground and airborne equipment.

2.3.1 Accuracy. The accuracy of course alignment of the VOR is excellent, being generally plus or minus 1 degree.

2.3.2 Roughness. On some VORs, minor course roughness may be observed, evidenced by course needle or brief flag alarm activity (some receivers are more subject to these irregularities than others). At a few stations, usually in mountainous terrain, the pilot may occasionally observe a brief course needle oscillation, similar to the indication of “approaching station.” Pilots flying over unfamiliar routes are cautioned to be on the alert of these vagaries, and, in particular, to use the “to-from” indicator to determine positive station passage.

2.3.2.1 Certain propeller RPM settings or helicopter rotor speeds can cause the VOR Course Deviation Indicator (CDI) to fluctuate as much as plus or minus six degrees. Slight changes to the RPM setting will normally smooth out this roughness. Pilots are urged to check for this modulation phenomenon prior to reporting a VOR station or aircraft equipment for unsatisfactory operation.

2.4 The only positive method of identifying a VOR is by its Morse Code identification or by the recorded automatic voice identification which is always indicated by use of the word “VOR” following the range's name. Reliance on determining the identification of an omnirange should never be placed on listening to voice transmissions by the FSS (or approach control facility) involved. Many FSS remotely operate several omniranges which have different names from each other and, in some cases, none have the name of the “parent” FSS. During periods of maintenance the facility may radiate a T-E-S-T code (- ● ●●● -) or the code may be removed. Some VOR equipment decodes the identifier and displays it to the pilot for verification to charts, while other equipment simply displays the expected identifier from a database to aid in verification to the audio tones. You should be familiar with your equipment and use it appropriately. If your equipment automatically decodes the identifier, it is not necessary to listen to the audio identification.

2.5 Voice identification has been added to numerous VORs. The transmission consists of a voice announcement; i.e., “AIRVILLE VOR,” alternating with the usual Morse Code identification.

2.6 The VOR Minimum Operational Network (MON). As flight procedures and route structure based on VORs are gradually being replaced with Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) procedures, the FAA is removing selected VORs from service. PBN procedures are primarily enabled by GPS and its augmentation systems, collectively referred to as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). Aircraft that carry DME/DME equipment can also use RNAV which provides a backup to continue flying PBN during a GNSS disruption. For those aircraft that do not carry DME/DME, the FAA is retaining a limited network of VORs, called the VOR MON, to provide a basic conventional navigation service for operators to use if GNSS becomes unavailable. During a GNSS disruption, the MON will enable aircraft to navigate through the affected area or to a safe landing at a MON airport without reliance on GNSS. Navigation using the MON will not be as efficient as the new PBN route structure, but use of the MON will provide nearly continuous VOR signal coverage at 5,000 feet AGL across the NAS, outside of the Western U.S. Mountainous Area (WUSMA).

The VOR MON has been retained principally for IFR aircraft that are not equipped with DME/DME avionics. However, VFR aircraft may use the MON as desired. Aircraft equipped with DME/DME navigation systems would, in most cases, use DME/DME to continue flight using RNAV to their destination. However, these aircraft may, of course, use the MON.

2.6.1 Distance to a MON airport. The VOR MON will ensure that regardless of an aircraft's position in the contiguous United States (CONUS), a MON airport (equipped with legacy ILS or VOR approaches) will be within 100 nautical miles. These airports are referred to as “MON airports” and will have an ILS approach or a VOR approach if an ILS is not available. VORs to support these approaches will be retained in the VOR MON. MON airports are charted on low-altitude en route charts and are contained in the Chart Supplement U.S. and other appropriate publications.

2.6.2 Navigating to an airport. The VOR MON will retain sufficient VORs to ensure that pilots will have nearly continuous signal reception of a VOR when flying at 5,000 feet AGL. The service volume of VORs will be increased to provide service at 5,000feet above the VOR. If the pilot encounters a GPS outage, the pilot will be able to proceed via VOR-to-VOR navigation at 5,000 feet above the VOR, either through the GPS outage area or to a safe landing at a MON airport or another suitable airport, as appropriate. Nearly all VORs inside of the WUSMA and outside the CONUS are being retained. In these areas, pilots use the existing (Victor and Jet) route structure and VORs to proceed through a GPS outage or to a landing.

2.6.3 Using the VOR MON.

2.6.3.1 In the case of a planned GPS outage (for example, one that is in a published NOTAM), pilots may plan to fly through the outage using the MON as appropriate and as cleared by ATC. Similarly, aircraft not equipped with GPS may plan to fly and land using the MON, as appropriate and as cleared by ATC.

2. Aircraft not equipped with GPS may be limited to a visual approach at the planned destination.

2.6.3.2 In the case of an unscheduled GPS outage, pilots and ATC will need to coordinate the best outcome for all aircraft. It is possible that a GPS outage could be disruptive, causing high workload and demand for ATC service. Generally, the VOR MON concept will enable pilots to navigate through the GPS outage or land at a MON airport or at another airport that may have an appropriate approach or may be in visual conditions.

a) The VOR MON is a reversionary service provided by the FAA for use by aircraft that are unable to continue RNAV during a GPS disruption. The FAA has not mandated that preflight or inflight planning include provisions for GPS- or WAAS-equipped aircraft to carry sufficient fuel to proceed to a MON airport in case of an unforeseen GPS outage. Specifically, flying to a MON airport as a filed alternate will not be explicitly required. Of course, consideration for the possibility of a GPS outage is prudent during flight planning as is maintaining proficiency with VOR navigation.

b) Also, in case of a GPS outage, pilots may coordinate with ATC and elect to continue through the outage or land. The VOR MON is designed to ensure that an aircraft is within 100 NM of an airport, but pilots may decide to proceed to any appropriate airport where a landing can be made, as coordinated with ATC. WAAS users flying under Part 91 are not required to carry VOR avionics. These users do not have the ability or requirement to use the VOR MON. Prudent flight planning, by these WAAS-only aircraft, should consider the possibility of a GPS outage.

3. VOR Receiver Check

3.1 Periodic VOR receiver calibration is most important. If a receiver's Automatic Gain Control or modulation circuit deteriorates, it is possible for it to display acceptable accuracy and sensitivity close into the VOR or VOT and display out-of-tolerance readings when located at greater distances where weaker signal areas exist. The likelihood of this deterioration varies between receivers, and is generally considered a function of time. The best assurance of having an accurate receiver is periodic calibration. Yearly intervals are recommended at which time an authorized repair facility should recalibrate the receiver to the manufacturer's specifications.

3.2 14 CFR Section 91.171 provides for certain VOR equipment accuracy checks prior to flight under IFR. To comply with this requirement and to ensure satisfactory operation of the airborne system, the FAA has provided pilots with the following means of checking VOR receiver accuracy:

3.2.1 FAA VOR test facility (VOT) or a radiated test signal from an appropriately rated radio repair station.

3.2.2 Certified airborne checkpoints and airways.

3.2.3 Certified check points on the airport surface.

3.2.4 If an airborne checkpoint is not available, select an established VOR airway. Select a prominent ground point, preferably more than 20 NM from the VOR ground facility and maneuver the aircraft directly over the point at reasonably low altitude above terrain and obstructions.

3.3 The FAA VOT transmits a test signal which provides a convenient means to determine the operational status and accuracy of a VOR receiver while on the ground where a VOT is located. The airborne use of VOT is permitted; however, its use is strictly limited to those areas/altitudes specifically authorized in the Chart Supplement or appropriate supplement. To use the VOT service, tune in the VOT frequency on your VOR receiver. With the CDI centered, the omni-bearing selector should read 0° with the to/from indicator showing “from,” or the omni-bearing selector should read 180° with the to/from indicator showing “to.” Should the VOR receiver operate a Radio Magnetic Indicator (RMI), it will indicate 180° on any OBS setting. Two means of identification are used. One is a series of dots, and the other is a continuous tone. Information concerning an individual test signal can be obtained from the local FSS.

3.4 A radiated VOR test signal from an appropriately rated radio repair station serves the same purpose as an FAA VOR signal and the check is made in much the same manner as a VOT with the following differences:

3.4.1 The frequency normally approved by the FCC is 108.0 MHz.

3.4.2 Repair stations are not permitted to radiate the VOR test signal continuously, consequently the owner/operator must make arrangements with the repair station to have the test signal transmitted. This service is not provided by all radio repair stations. The aircraft owner or operator must determine which repair station in the local area provides this service. A representative of the repair station must make an entry into the aircraft logbook or other permanent record certifying to the radial accuracy and the date of transmission. The owner/operator or representative of the repair station may accomplish the necessary checks in the aircraft and make a logbook entry stating the results. It is necessary to verify which test radial is being transmitted and whether you should get a “to” or “from” indication.

3.5 Airborne and ground check points consist of certified radials that should be received at specific points on the airport surface, or over specific landmarks while airborne in the immediate vicinity of the airport.

3.5.1 Should an error in excess of plus or minus 4 degrees be indicated through use of a ground check, or plus or minus 6 degrees using the airborne check, IFR flight must not be attempted without first correcting the source of the error.

3.5.2 Locations of airborne check points, ground check points and VOTs are published in the Chart Supplement.

3.5.3 If a dual system VOR (units independent of each other except for the antenna) is installed in the aircraft, one system may be checked against the other. Turn both systems to the same VOR ground facility and note the indicated bearing to that station. The maximum permissible variations between the two indicated bearings is 4 degrees.

4. Distance Measuring Equipment (DME)

4.1 In the operation of DME, paired pulses at a specific spacing are sent out from the aircraft (this is the interrogation) and are received at the ground station. The ground station (transponder) then transmits paired pulses back to the aircraft at the same pulse spacing but on a different frequency. The time required for the round trip of this signal exchange is measured in the airborne DME unit and is translated into distance (nautical miles (NM)) from the aircraft to the ground station.

4.2 Operating on the line-of-sight principle, DME furnishes distance information with a very high degree of accuracy. Reliable signals may be received at distances up to 199 NM at line-of-sight altitude with an accuracy of better than 1/2 mile or 3% of the distance, whichever is greater. Distance information received from DME equipment is SLANT RANGE distance and not actual horizontal distance.

4.3 Operating frequency range of a DME according to ICAO Annex 10 is from 960 MHz to 1215 MHz. Aircraft equipped with TACAN equipment will receive distance information from a VORTAC automatically, while aircraft equipped with VOR must have a separate DME airborne unit.

4.4 VOR/DME, VORTAC, ILS/DME, and LOC/DME navigation facilities established by the FAA provide course and distance information from collocated components under a frequency pairing plan. Aircraft receiving equipment which provides for automatic DME selection assures reception of azimuth and distance information from a common source whenever designated VOR/DME, VORTAC, ILS/DME, and LOC/DME are selected.

4.5 Due to the limited number of available frequencies, assignment of paired frequencies is required for certain military noncollocated VOR and TACAN facilities which serve the same area but which may be separated by distances up to a few miles.

4.6 VOR/DME, VORTAC, ILS/DME, and LOC/DME facilities are identified by synchronized identifications which are transmitted on a time share basis. The VOR or localizer portion of the facility is identified by a coded tone modulated at 1020 Hz or by a combination of code and voice. The TACAN or DME is identified by a coded tone modulated at 1350 Hz. The DME or TACAN coded identification is transmitted one time for each three or four times that the VOR or localizer coded identification is transmitted. When either the VOR or the DME is inoperative, it is important to recognize which identifier is retained for the operative facility. A signal coded identification with a repetition interval of approximately 30 seconds indicates that the DME is operative.

4.7 Aircraft equipment which provides for automatic DME selection assures reception of azimuth and distance information from a common source whenever designated VOR/DME, VORTAC, and ILS/DME navigation facilities are selected. Pilots are cautioned to disregard any distance displays from automatically selected DME equipment when VOR or ILS facilities, which do not have the DME feature installed, are being used for position determination.

5. Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN)

5.1 For reasons peculiar to military or naval operations (unusual siting conditions, the pitching and rolling of a naval vessel, etc.) the civil VOR/DME system of air navigation was considered unsuitable for military or naval use. A new navigational system, Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN), was therefore developed by the military and naval forces to more readily lend itself to military and naval requirements. As a result, the FAA has integrated TACAN facilities with the civil VOR/DME program. Although the theoretical, or technical principles of operation of TACAN equipment are quite different from those of VOR/DME facilities, the end result, as far as the navigating pilot is concerned, is the same. These integrated facilities are called VORTACs.

5.2 TACAN ground equipment consists of either a fixed or mobile transmitting unit. The airborne unit in conjunction with the ground unit reduces the transmitted signal to a visual presentation of both azimuth and distance information. TACAN is a pulse system and operates in the UHF band of frequencies. Its use requires TACAN airborne equipment and does not operate through conventional VOR equipment.

5.3 A VORTAC is a facility consisting of two components, VOR and TACAN, which provides three individual services: VOR azimuth, TACAN azimuth, and TACAN distance (DME) at one site. Although consisting of more than one component, incorporating more than one operating frequency, and using more than one antenna system, a VORTAC is considered to be a unified navigational aid. Both components of a VORTAC are envisioned as operating simultaneously and providing the three services at all times.

5.4 Transmitted signals of VOR and TACAN are each identified by three-letter code transmission and are interlocked so that pilots using VOR azimuth and TACAN distance can be assured that both signals being received are definitely from the same ground station. The frequency channels of the VOR and the TACAN at each VORTAC facility are “paired” in accordance with a national plan to simplify airborne operation.

6. Instrument Landing System (ILS)

6.1 General

6.1.1 The ILS is designed to provide an approach path for exact alignment and descent of an aircraft on final approach to a runway.

6.1.2 The basic components of an ILS are the localizer, glide slope, and Outer Marker (OM) and, when installed for use with Category II or Category III instrument approach procedures, an Inner Marker (IM).

6.1.3 The system may be divided functionally into three parts:

6.1.3.1 Guidance information: localizer, glide slope.

6.1.3.2 Range information: marker beacon, DME.

6.1.3.3 Visual information: approach lights, touchdown and centerline lights, runway lights.

6.1.4 The following means may be used to substitute for the OM:

6.1.4.1 Compass locator; or

6.1.4.2 Precision Approach Radar (PAR); or

6.1.4.3 Airport Surveillance Radar (ASR); or

6.1.4.4 Distance Measuring Equipment (DME), Very High Frequency Omni-directional Range (VOR), or Nondirectional beacon fixes authorized in the Standard Instrument Approach Procedure; or

6.1.4.5 A suitable RNAV system with Global Positioning System (GPS), capable of fix identification on a Standard Instrument Approach Procedure.

6.1.5 Where a complete ILS system is installed on each end of a runway (i.e., the approach end of runway 4 and the approach end of runway 22), the ILS systems are not in service simultaneously.

6.2 Localizer

6.2.1 The localizer transmitter, operates on one of 40 ILS channels within the frequency range of 108.10 MHz to 111.95 MHz. Signals provide the pilot with course guidance to the runway centerline.

6.2.2 The approach course of the localizer is called the front course and is used with other functional parts; e.g., glide slope, marker beacons, etc. The localizer signal is transmitted at the far end of the runway. It is adjusted for a course width (full scale fly-left to a full scale fly-right) of 700 feet at the runway threshold.

6.2.3 The course line along the extended centerline of a runway, in the opposite direction to the front course, is called the back course.

6.2.4 Identification is in Morse Code and consists of a three-letter identifier preceded by the letter I (●●) transmitted on the localizer frequency.

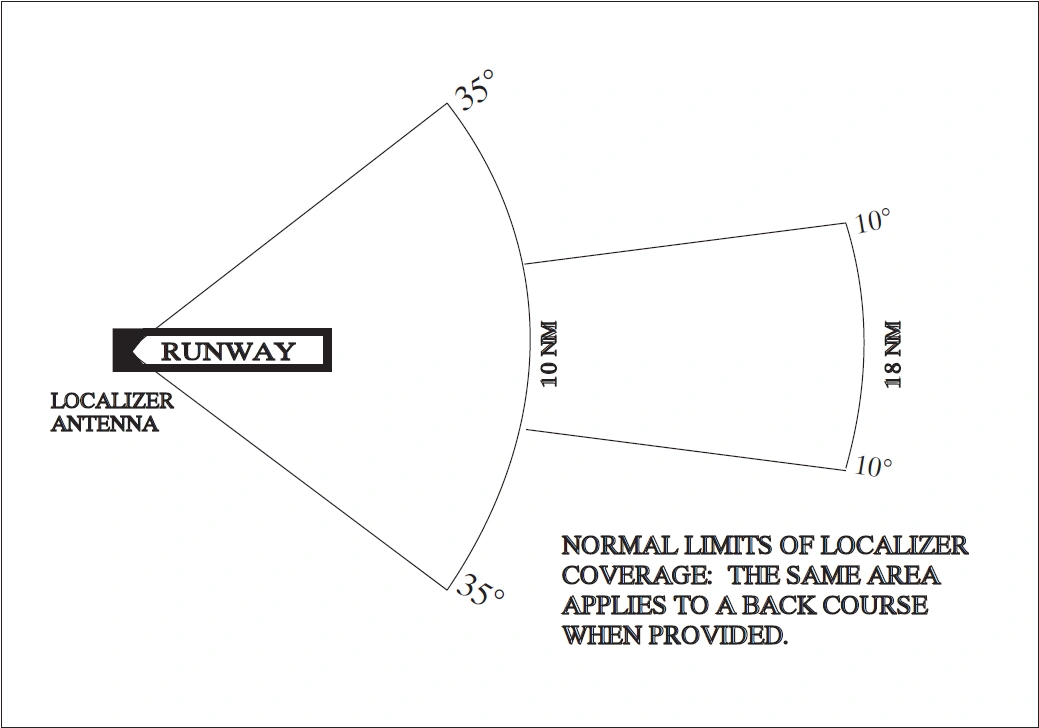

6.2.5 The localizer provides course guidance throughout the descent path to the runway threshold from a distance of 18 NM from the antenna between an altitude of 1,000 feet above the highest terrain along the course line and 4,500 feet above the elevation of the antenna site. Proper off-course indications are provided throughout the following angular areas of the operational service volume:

6.2.5.1 To 10° either side of the course along a radius of 18 NM from the antenna.

6.2.5.2 From 10° to 35°either side of the course along a radius of 10 NM. (See FIG ENR 4.1-1.)

6.2.6 Unreliable signals may be received outside of these areas. ATC may clear aircraft on procedures beyond the service volume when the controller initiates the action or when the pilot requests, and radar monitoring is provided.

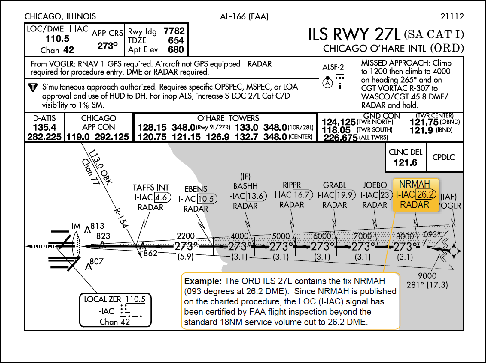

6.2.7 The areas described in paragraph 6.2.5 and depicted in FIG ENR 4.1-1 represent a Standard Service Volume (SSV) localizer. All charted procedures with localizer coverage beyond the 18 NM SSV have been through the approval process for Expanded Service Volume (ESV), and have been validated by flight inspection. (See FIG ENR 4.1-2.)

Limits of Localizer Coverage

ILS Expanded Service Volume

6.3 Localizer-Type Directional Aid

6.3.1 The localizer-type directional aid (LDA) is of comparable use and accuracy to a localizer but is not part of a complete ILS. The LDA course usually provides a more precise approach course than the similar Simplified Directional Facility (SDF) installation, which may have a course width of 6 degrees or 12 degrees.

6.3.2 The LDA is not aligned with the runway. Straight-in minimums may be published where alignment does not exceed 30 degrees between the course and runway. Circling minimums only are published where this alignment exceeds 30 degrees.

6.3.3 A very limited number of LDA approaches also incorporate a glideslope. These are annotated in the plan view of the instrument approach chart with a note, “LDA/Glideslope.” These procedures fall under a newly defined category of approaches called Approach with Vertical Guidance (APV) described in ENR 1.5, Paragraph 12., Instrument Approach Procedure Charts, subparagraph 12.1.7.2, Approach with Vertical Guidance (APV). LDA minima for with and without glideslope is provided and annotated on the minima lines of the approach chart as S-LDA/GS and S-LDA. Because the final approach course is not aligned with the runway centerline, additional maneuvering will be required compared to an ILS approach.

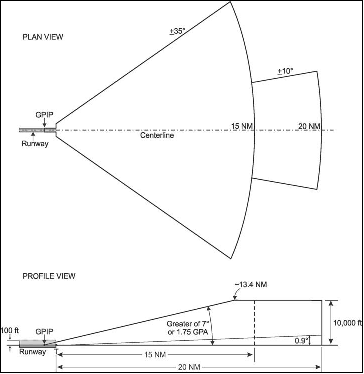

6.4 Glide Slope/Glide Path

6.4.1 The UHF glide slope transmitter, operating on one of the 40 ILS channels within the frequency range 329.15 MHz, to 335.00 MHz radiates its signals in the direction of the localizer front course.

6.4.2 The glide slope transmitter is located between 750 and 1,250 feet from the approach end of the runway (down the runway) and offset 250-600 feet from the runway centerline. It transmits a glide path beam 1.4 degrees wide (vertically).

6.4.3 The glide path projection angle is normally adjusted to 3 degrees above horizontal so that it intersects the middle marker at about 200 feet and the outer marker at about 1,400 feet above the runway elevation. The glide slope is normally usable to the distance of 10 NM. However, at some locations, the glide slope has been certified for an extended service volume which exceeds 10 NM.

6.4.4 Pilots must be alert when approaching glidepath interception. False courses and reverse sensing will occur at angles considerably greater than the published path.

6.4.5 Make every effort to remain on the indicated glide path. Exercise caution: avoid flying below the glide path to assure obstacle/terrain clearance is maintained.

6.4.6 A glide slope facility provides descent information for navigation down to the lowest authorized decision height (DH) specified in the approved ILS approach procedure. The glidepath may not be suitable for navigation below the lowest authorized DH and any reference to glidepath indications below that height must be supplemented by visual reference to the runway environment. Glide slopes with no published DH are usable to runway threshold.

6.4.7 The published glide slope threshold crossing height (TCH) DOES NOT represent the height of the actual glide slope on course indication above the runway threshold. It is used as a reference for planning purposes which represents the height above the runway threshold that an aircraft's glide slope antenna should be, if that aircraft remains on a trajectory formed by the four-mile-to-middle marker glidepath segment.

6.4.8 Pilots must be aware of the vertical height between the aircraft's glide slope antenna and the main gear in the landing configuration and, at the DH, plan to adjust the descent angle accordingly if the published TCH indicates the wheel crossing height over the runway threshold may be satisfactory. Tests indicate a comfortable wheel crossing height is approximately 20 to 30 feet, depending on the type of aircraft.

6.5 Distance Measuring Equipment (DME)

6.5.1 When installed with an ILS and specified in the approach procedure, DME may be used:

6.5.1.1 In lieu of the outer marker.

6.5.1.2 As a back course final approach fix.

6.5.1.3 To establish other fixes on the localizer course.

6.5.2 In some cases, DME from a separate facility may be used within Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) limitations:

6.5.2.1 To provide ARC initial approach segments.

6.5.2.2 As a final approach fix for back course approaches.

6.5.2.3 As a substitute for the outer marker.

6.6 Marker Beacon

6.6.1 ILS marker beacons have a rated power output of 3 watts or less and an antenna array designed to produce an elliptical pattern with dimensions, at 1,000 feet above the antenna, of approximately 2,400 feet in width and 4,200 feet in length. Airborne marker beacon receivers with a selective sensitivity feature should always be operated in the “low” sensitivity position for proper reception of ILS marker beacons.

6.6.2 ILS systems may have an associated OM. An MM is no longer required. Locations with a Category II ILS also have an Inner Marker (IM). Due to advances in both ground navigation equipment and airborne avionics, as well as the numerous means that may be used as a substitute for a marker beacon, the current requirements for the use of marker beacons are:

6.6.2.1 An OM or suitable substitute identifies the Final Approach Fix (FAF) for nonprecision approach (NPA) operations (for example, localizer only); and

6.6.2.2 The MM indicates a position approximately 3,500 feet from the landing threshold. This is also the position where an aircraft on the glide path will be at an altitude of approximately 200 feet above the elevation of the touchdown zone. A MM is no longer operationally required. There are some MMs still in use, but there are no MMs being installed at new ILS sites by the FAA; and

6.6.2.3 An IM, where installed, indicates the point at which an aircraft is at decision height on the glide path during a Category II ILS approach. An IM is only required for CAT II operations that do not have a published radio altitude (RA) minimum.

6.6.3 A back course marker, normally indicates the ILS back course final approach fix where approach descent is commenced.

TBL ENR 4.1-1 Marker Passage Indications

|

Marker |

Code |

Light |

|

OM |

− −×− |

BLUE |

|

MM |

● ×− ● − |

AMBER |

|

IM |

● ● ● ● |

WHITE |

|

BC |

● ● ● ● |

WHITE |

7. Compass Locator

7.1 Compass locator transmitters are often situated at the middle and outer marker sites. The transmitters have a power of less than 25 watts, a range of at least 15 miles, and operate between 190 and 535 kHz. At some locations, higher-powered radio beacons, up to 400 watts, are used as outer marker compass locators.

7.2 Compass locators transmit two-letter identification groups. The outer locator transmits the first two letters of the localizer identification group, and the middle locator transmits the last two letters of the localizer identification group.

8. ILS Frequency

8.1 The frequency pairs in TBL ENR 4.1-2 are allocated for ILS.

TBL ENR 4.1-2 Frequency Pairs Allocated for ILS

|

Localizer MHz |

Glide Slope |

|

108.10 |

334.70 |

|

108.15 |

334.55 |

|

108.3 |

334.10 |

|

108.35 |

333.95 |

|

108.5 |

329.90 |

|

108.55 |

329.75 |

|

108.7 |

330.50 |

|

108.75 |

330.35 |

|

108.9 |

329.30 |

|

108.95 |

329.15 |

|

109.1 |

331.40 |

|

109.15 |

331.25 |

|

109.3 |

332.00 |

|

109.35 |

331.85 |

|

109.50 |

332.60 |

|

109.55 |

332.45 |

|

109.70 |

333.20 |

|

109.75 |

333.05 |

|

109.90 |

333.80 |

|

109.95 |

333.65 |

|

Localizer MHz |

Glide Slope |

|

110.1 |

334.40 |

|

110.15 |

334.25 |

|

110.3 |

335.00 |

|

110.35 |

334.85 |

|

110.5 |

329.60 |

|

110.55 |

329.45 |

|

110.70 |

330.20 |

|

110.75 |

330.05 |

|

110.90 |

330.80 |

|

110.95 |

330.65 |

|

111.10 |

331.70 |

|

111.15 |

331.55 |

|

111.30 |

332.30 |

|

111.35 |

332.15 |

|

111.50 |

332.9 |

|

111.55 |

332.75 |

|

111.70 |

333.5 |

|

111.75 |

333.35 |

|

111.90 |

331.1 |

|

111.95 |

330.95 |

9. ILS Minimums

9.1 The lowest authorized ILS minimums, with all required ground and airborne systems components operative, are:

9.1.1 Category I. Decision Height (DH) 200 feet and Runway Visual Range (RVR) 2,400 feet (with touchdown zone and centerline lighting, RVR 1,800 feet), or (with Autopilot or FD or HUD, RVR 1,800 feet);

9.1.2 Special Authorization Category I. DH 150 feet and Runway Visual Range (RVR) 1,400 feet, HUD to DH;

9.1.3 Category II. DH 100 feet and RVR 1,200 feet (with autoland or HUD to touchdown and noted on authorization, RVR 1,000 feet);

9.1.4 Special Authorization Category II with Reduced Lighting. DH 100 feet and RVR 1,200 feet with autoland or HUD to touchdown and noted on authorization, (touchdown zone, centerline lighting and ALSF-2 are not required);

9.1.5 Category IIIa. No DH or DH below 100 feet and RVR not less than 700 feet;

9.1.6 Category IIIb. No DH or DH below 50 feet and RVR less than 700 feet but not less than 150 feet; and

9.1.7 Category IIIc. No DH and no RVR limitation.

10. Inoperative ILS Components

10.1 Inoperative Localizer. When the localizer fails, an ILS approach is not authorized.

10.2 Inoperative Glide Slope. When the glide slope fails, the ILS reverts to a nonprecision localizer approach.

11. ILS Course and Glideslope Distortion

11.1 All pilots should be aware that ILS installations are subject to signal interference by surface vehicles and aircraft (either on the ground or airborne). ILS CRITICAL AREAS are established near each localizer and glide slope antenna. Pilots should be aware of the level of critical area protection they can expect in various weather conditions and understand that signal disturbances may occur as a result of normal airport operations irrespective of the official weather observation.

11.2 ATC is not always required to issue control instructions to avoid interfering operations within ILS critical areas at controlled airports during the hours the Airport Traffic Control Tower (ATCT) is in operation. ATC responsibilities vary depending on the official weather observation and are described as follows:

11.2.1 Weather Conditions. Official weather observation indicates a ceiling of 800 feet or higher and visibility 2 miles or greater, no localizer or glideslope critical area protection is provided by ATC unless specifically requested by the flight crew.

11.2.2 Weather Conditions. Official weather observation indicates a ceiling of less than 800 feet or visibility less than 2 miles.

11.2.2.1 Holding. Aircraft holding below 5,000 feet between the outer marker and the airport may cause localizer signal variations for aircraft conducting the ILS approach. Accordingly, such holding will not be authorized by ATC.

11.2.2.2 Localizer Critical Area. When an arriving aircraft is inside the outer marker (OM) or the fix used in lieu of the OM, vehicles and aircraft will not be authorized in or over the precision approach critical area except:

a) A preceding arriving aircraft on the same or another runway may pass over or through the localizer critical area, and;

b) A preceding departing aircraft or missed approach on the same or another runway may pass through or over the localizer critical area.

11.2.2.3 Glide Slope Critical Area. ATC will not authorize vehicles or aircraft operations in or over the glideslope critical area when an arriving aircraft is inside the outer marker (OM), or the fix used in lieu of the OM, unless the arriving aircraft has reported the runway in sight and is circling or side-stepping to land on another runway.

11.2.3 Weather Conditions. Official weather observation indicates a ceiling less than 200 feet or runway visual range (RVR) less than 2000 feet.

11.2.3.1 Localizer Critical Area. In addition to the critical area protection described in 11.2.2 above, when an arriving aircraft is inside the middle marker (MM), or in the absence of a MM, ½ mile final, ATC will not authorize:

a) A preceding arriving aircraft on the same or another runway to pass over or through the localizer critical area, or;

b) A preceding departing aircraft or missed approach on the same or another runway to pass through or over the localizer critical area.

11.3 In order to ensure that pilot and controller expectations match with respect to critical area protection for a given approach and landing operation, a flight crew should advise the tower any time it intends to conduct any autoland operation or use an SA CAT I, any CAT II, or any CAT III line of minima anytime the official weather observation is at or above a ceiling of 800 feet and 2 miles visibility. If ATC is unable to protect the critical area, they will advise the flight crew.

11.4 Pilots are cautioned that even when the critical areas are considered to be protected, unless the official weather observation including controller observations indicates a ceiling less than 200 feet or RVR less than 2000 feet, ATC may still authorize a preceding arriving, departing, or missed approach aircraft to pass through or over the localizer critical area and that this may cause signal disturbances that could result in an undesired aircraft state during the final stages of the approach, landing, and rollout.

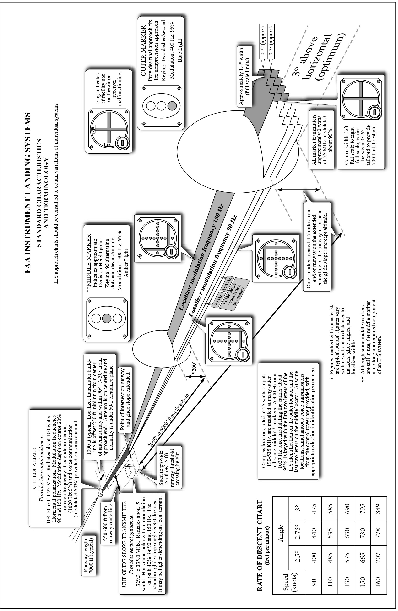

11.5 Pilots are cautioned that vehicular traffic not subject to ATC may cause momentary deviation to ILS course or glide slope signals. Also, critical areas are not protected at uncontrolled airports or at airports with an operating control tower when weather or visibility conditions are above those requiring protective measures. Aircraft conducting coupled or autoland operations should be especially alert in monitoring automatic flight control systems and be prepared to intervene as necessary. (See FIG ENR 4.1-3.)

FAA Instrument Landing Systems

12. Continuous Power Facilities

12.1 In order to ensure that a basic ATC system remains in operation despite an area wide or catastrophic commercial power failure, key equipment and certain airports have been designated to provide a network of facilities whose operational capability can be utilized independent of any commercial power supply.

12.2 In addition to those facilities comprising the basic ATC system, the following approach and lighting aids have been included in this program for a selected runway:

12.2.1 ILS (Localizer, Glide Slope, Compass Locator, Inner, Middle and Outer Markers).

12.2.2 Wind Measuring Capability.

12.2.3 Approach Light System (ALS) or Short ALS (SALS).

12.2.4 Ceiling Measuring Capability.

12.2.5 Touchdown Zone Lighting (TDZL).

12.2.6 Centerline Lighting (CL).

12.2.7 Runway Visual Range (RVR).

12.2.8 High Intensity Runway Lighting (HIRL).

12.2.9 Taxiway Lighting.

12.2.10 Apron Light (Perimeter Only).

TBL ENR 4.1-3 Continuous Power Airports

|

Airport/Ident |

Runway No. |

|

Albuquerque (ABQ) |

08 |

|

Andrews AFB (ADW) |

1L |

|

Atlanta (ATL) |

9R |

|

Baltimore (BWI) |

10 |

|

Bismarck (BIS) |

31 |

|

Boise (BOI) |

10R |

|

Boston (BOS) |

4R |

|

Charlotte (CLT) |

36L |

|

Chicago (ORD) |

14R |

|

Cincinnati (CVG) |

36 |

|

Cleveland (CLE) |

5R |

|

Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW) |

17L |

|

Denver (DEN) |

35R |

|

Des Moines (DSM) |

30R |

|

Detroit (DTW) |

3L |

|

El Paso (ELP) |

22 |

|

Great Falls (GTF) |

03 |

|

Houston (IAH) |

08 |

|

Indianapolis (IND) |

4L |

|

Jacksonville (JAX) |

07 |

|

Kansas City (MCI) |

19 |

|

Los Angeles (LAX) |

24R |

|

Memphis (MEM) |

36L |

|

Airport/Ident |

Runway No. |

|

Miami (MIA) |

9L |

|

Milwaukee (MKE) |

01 |

|

Minneapolis (MSP) |

29L |

|

Nashville (BNA) |

2L |

|

Newark (EWR) |

4R |

|

New Orleans (MSY) |

10 |

|

New York (JFK) |

4R |

|

New York (LGA) |

22 |

|

Oklahoma City (OKC) |

35R |

|

Omaha (OMA) |

14 |

|

Ontario, California (ONT) |

26R |

|

Philadelphia (PHL) |

9R |

|

Phoenix (PHX) |

08R |

|

Pittsburgh (PIT) |

10L |

|

Reno (RNO) |

16 |

|

Salt Lake City (SLC) |

34L |

|

San Antonio (SAT) |

12R |

|

San Diego (SAN) |

09 |

|

San Francisco (SFO) |

28R |

|

Seattle (SEA) |

16R |

|

St. Louis (STL) |

24 |

|

Tampa (TPA) |

36L |

|

Tulsa (TUL) |

35R |

|

Washington (DCA) |

36 |

|

Washington (IAD) |

1R |

|

Wichita (ICT) |

01 |

12.3 The above have been designated “Continuous Power Airports,” and have independent back up capability for the equipment installed.

13. Simplified Directional Facility (SDF)

13.1 The SDF provides a final approach course similar to that of the ILS localizer. It does not provide glide slope information. A clear understanding of the ILS localizer and the additional factors listed below completely describe the operational characteristics and use of the SDF.

13.2 The SDF transmits signals within the range of 108.10 to 111.95 MHz.

13.3 The approach techniques and procedures used in an SDF instrument approach are essentially the same as those employed in executing a standard no-glide-slope localizer approach except the SDF course may not be aligned with the runway and the course may be wider, resulting in less precision.

13.4 Usable off-course indications are limited to 35 degrees either side of the course centerline. Instrument indications received beyond 35 degrees should be disregarded.

13.5 The SDF antenna may be offset from the runway centerline. Because of this, the angle of convergence between the final approach course and the runway bearing should be determined by reference to the instrument approach procedure chart. This angle is generally not more than 3 degrees. However, it should be noted that inasmuch as the approach course originates at the antenna site, an approach which is continued beyond the runway threshold will lead the aircraft to the SDF offset position rather than along the runway centerline.

13.6 The SDF signal is fixed at either 6 degrees or 12 degrees as necessary to provide maximum “fly ability” and optimum course quality.

13.7 Identification consists of a three-letter identifier transmitted in Morse Code on the SDF frequency. The appropriate instrument approach chart will indicate the identifier used at a particular airport.

14. LORAN

15. Inertial Reference Unit (IRU), Inertial Navigation System (INS), and Attitude Heading Reference System (AHRS)

15.1 IRUs are self-contained systems comprised of gyros and accelerometers that provide aircraft attitude (pitch, roll, and heading), position, and velocity information in response to signals resulting from inertial effects on system components. Once aligned with a known position, IRUs continuously calculate position and velocity. IRU position accuracy decays with time. This degradation is known as “drift.”

15.2 INSs combine the components of an IRU with an internal navigation computer. By programming a series of waypoints, these systems will navigate along a predetermined track.

15.3 AHRSs are electronic devices that provide attitude information to aircraft systems such as weather radar and autopilot, but do not directly compute position information.

15.4 Aircraft equipped with slaved compass systems may be susceptible to heading errors caused by exposure to magnetic field disturbances (flux fields) found in materials that are commonly located on the surface or buried under taxiways and ramps. These materials generate a magnetic flux field that can be sensed by the aircraft's compass system flux detector or “gate”, which can cause the aircraft's system to align with the material's magnetic field rather than the earth's natural magnetic field. The system's erroneous heading may not self-correct. Prior to take off pilots should be aware that a heading misalignment may have occurred during taxi. Pilots are encouraged to follow the manufacturer's or other appropriate procedures to correct possible heading misalignment before take off is commenced.

16. Global Positioning System (GPS)

16.1 System Overview

16.1.1 System Description. The Global Positioning System is a space-based radio navigation system used to determine precise position anywhere in the world. The 24 satellite constellation is designed to ensure at least five satellites are always visible to a user worldwide. A minimum of four satellites is necessary for receivers to establish an accurate three-dimensional position. The receiver uses data from satellites above the mask angle (the lowest angle above the horizon at which a receiver can use a satellite). The Department of Defense (DOD) is responsible for operating the GPS satellite constellation and monitors the GPS satellites to ensure proper operation. Each satellite's orbital parameters (ephemeris data) are sent to each satellite for broadcast as part of the data message embedded in the GPS signal. The GPS coordinate system is the Cartesian earth-centered, earth-fixed coordinates as specified in the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS-84).

16.1.2 System Availability and Reliability

16.1.2.1 The status of GPS satellites is broadcast as part of the data message transmitted by the GPS satellites. GPS status information is also available by means of the U.S. Coast Guard navigation information service: (703) 313-5907, Internet: http://www.navcen.uscg.gov/. Additionally, satellite status is available through the Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) system.

16.1.2.2 GNSS operational status depends on the type of equipment being used. For GPS-only equipment TSO-C129 or TSO-C196(), the operational status of non-precision approach capability for flight planning purposes is provided through a prediction program that is embedded in the receiver or provided separately.

16.1.3 Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (RAIM). RAIM is the capability of a GPS receiver to perform integrity monitoring on itself by ensuring available satellite signals meet the integrity requirements for a given phase of flight. Without RAIM, the pilot has no assurance of the GPS position integrity. RAIM provides immediate feedback to the pilot. This fault detection is critical for performance-based navigation (PBN)(see ENR 1.16, Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) and Area Navigation (RNAV), for an introduction to PBN), because delays of up to two hours can occur before an erroneous satellite transmission is detected and corrected by the satellite control segment.

16.1.3.1 In order for RAIM to determine if a satellite is providing corrupted information, at least one satellite, in addition to those required for navigation, must be in view for the receiver to perform the RAIM function. RAIM requires a minimum of 5 satellites, or 4 satellites and barometric altimeter input (baro-aiding), to detect an integrity anomaly. Baro-aiding is a method of augmenting the GPS integrity solution by using a non-satellite input source in lieu of the fifth satellite. Some GPS receivers also have a RAIM capability, called fault detection and exclusion (FDE), that excludes a failed satellite from the position solution; GPS receivers capable of FDE require 6 satellites or 5 satellites with baro-aiding. This allows the GPS receiver to isolate the corrupt satellite signal, remove it from the position solution, and still provide an integrity-assured position. To ensure that baro-aiding is available, enter the current altimeter setting into the receiver as described in the operating manual. Do not use the GPS derived altitude due to the large GPS vertical errors that will make the integrity monitoring function invalid.

16.1.3.2 There are generally two types of RAIM fault messages. The first type of message indicates that there are not enough satellites available to provide RAIM integrity monitoring. The GPS navigation solution may be acceptable, but the integrity of the solution cannot be determined. The second type indicates that the RAIM integrity monitor has detected a potential error and that there is an inconsistency in the navigation solution for the given phase of flight. Without RAIM capability, the pilot has no assurance of the accuracy of the GPS position.

16.1.4 Selective Availability. Selective Availability (SA) is a method by which the accuracy of GPS is intentionally degraded. This feature was designed to deny hostile use of precise GPS positioning data. SA was discontinued on May 1, 2000, but many GPS receivers are designed to assume that SA is still active. New receivers may take advantage of the discontinuance of SA based on the performance values in ICAO Annex 10.

16.2 Operational Use of GPS. U.S. civil operators may use approved GPS equipment in oceanic airspace, certain remote areas, the National Airspace System and other States as authorized (please consult the applicable Aeronautical Information Publication). Equipage other than GPS may be required for the desired operation. GPS navigation is used for both Visual Flight Rules (VFR) and Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) operations.

16.2.1 VFR Operations

16.2.1.1 GPS navigation has become an asset to VFR pilots by providing increased navigational capabilities and enhanced situational awareness. Although GPS has provided many benefits to the VFR pilot, care must be exercised to ensure that system capabilities are not exceeded. VFR pilots should integrate GPS navigation with electronic navigation (when possible), as well as pilotage and dead reckoning.

16.2.1.2 GPS receivers used for VFR navigation vary from fully integrated IFR/VFR installation used to support VFR operations to hand-held devices. Pilots must understand the limitations of the receivers prior to using in flight to avoid misusing navigation information. (See TBL ENR 4.1-5.) Most receivers are not intuitive. The pilot must learn the various keystrokes, knob functions, and displays that are used in the operation of the receiver. Some manufacturers provide computer-based tutorials or simulations of their receivers that pilots can use to become familiar with operating the equipment.

16.2.1.3 When using GPS for VFR operations, RAIM capability, database currency, and antenna location are critical areas of concern.

a) RAIM Capability. VFR GPS panel mount receivers and hand-held units have no RAIM alerting capability. This prevents the pilot from being alerted to the loss of the required number of satellites in view, or the detection of a position error. Pilots should use a systematic cross-check with other navigation techniques to verify position. Be suspicious of the GPS position if a disagreement exists between the two positions.

b) Database Currency. Check the currency of the database. Databases must be updated for IFR operations and should be updated for all other operations. However, there is no requirement for databases to be updated for VFR navigation. It is not recommended to use a moving map with an outdated database in and around critical airspace. Pilots using an outdated database should verify waypoints using current aeronautical products; for example, Chart Supplement, Sectional Chart, or En Route Chart.

c) Antenna Location. The antenna location for GPS receivers used for IFR and VFR operations may differ. VFR antennae are typically placed for convenience more than performance, while IFR installations ensure a clear view is provided with the satellites. Antennae not providing a clear view have a greater opportunity to lose the satellite navigational signal. This is especially true in the case of hand-held GPS receivers. Typically, suction cups are used to place the GPS antennas on the inside of cockpit windows. While this method has great utility, the antenna location is limited to the cockpit or cabin which rarely provides a clear view of all available satellites. Consequently, signal losses may occur due to aircraft structure blocking satellite signals, causing a loss of navigation capability. These losses, coupled with a lack of RAIM capability, could present erroneous position and navigation information with no warning to the pilot. While the use of a hand-held GPS for VFR operations is not limited by regulation, modification of the aircraft, such as installing a panel- or yoke-mounted holder, is governed by 14 CFR Part 43. Consult with your mechanic to ensure compliance with the regulation and safe installation.

16.2.1.4 Do not solely rely on GPS for VFR navigation. No design standard of accuracy or integrity is used for a VFR GPS receiver. VFR GPS receivers should be used in conjunction with other forms of navigation during VFR operations to ensure a correct route of flight is maintained. Minimize head-down time in the aircraft by being familiar with your GPS receiver's operation and by keeping eyes outside scanning for traffic, terrain, and obstacles.

16.2.1.5 VFR Waypoints

a) VFR waypoints provide VFR pilots with a supplementary tool to assist with position awareness while navigating visually in aircraft equipped with area navigation receivers. VFR waypoints should be used as a tool to supplement current navigation procedures. The uses of VFR waypoints include providing navigational aids for pilots unfamiliar with an area, waypoint definition of existing reporting points, enhanced navigation in and around Class B and Class C airspace, enhanced navigation around Special Use Airspace, and entry points for commonly flown mountain passes. VFR pilots should rely on appropriate and current aeronautical charts published specifically for visual navigation. If operating in a terminal area, pilots should take advantage of the Terminal Area Chart available for that area, if published. The use of VFR waypoints does not relieve the pilot of any responsibility to comply with the operational requirements of 14 CFR Part 91.

b) VFR waypoint names (for computer entry and flight plans) consist of five letters beginning with the letters “VP” and are retrievable from navigation databases. The VFR waypoint names are not intended to be pronounceable, and they are not for use in ATC communications. On VFR charts, stand-alone VFR waypoints will be portrayed using the same four-point star symbol used for IFR waypoints. VFR waypoints collocated with visual check-points on the chart will be identified by small magenta flag symbols. VFR waypoints collocated with visual check-points will be pronounceable based on the name of the visual check-point and may be used for ATC communications. Each VFR waypoint name will appear in parentheses adjacent to the geographic location on the chart. Latitude/longitude data for all established VFR waypoints is accessible through in FAA Order JO 7350.9, Location Identifiers.

c) VFR waypoints may not be used on IFR flight plans. VFR waypoints are not recognized by the IFR system and will be rejected for IFR routing purposes.

d) Pilots may use the five-letter identifier as a waypoint in the route of flight section on a VFR flight plan. Pilots may use the VFR waypoints only when operating under VFR conditions. The point may represent an intended course change or describe the planned route of flight. This VFR filing would be similar to how a VOR would be used in a route of flight.

e) VFR waypoints intended for use during flight should be loaded into the receiver while on the ground. Once airborne, pilots should avoid programming routes or VFR waypoint chains into their receivers.

f) Pilots should be vigilant to see and avoid other traffic when near VFR waypoints. With the increased use of GPS navigation and accuracy, expect increased traffic near VFR waypoints. Regardless of the class of airspace, monitor the available ATC frequency for traffic information on other aircraft operating in the vicinity. See ENR 1.16, paragraph NO TAG# VFR in Congested Areas, for more information.

g) Mountain pass entry points are marked for convenience to assist pilots with flight planning and visual navigation. Do not attempt to fly a mountain pass directly from VFR waypoint to VFR waypoint—they do not create a path through the mountain pass. Alternative routes are always available. It is the pilot in command's responsibility to choose a suitable route for the intended flight and known conditions.

16.2.2 IFR Use of GPS

16.2.2.1 General Requirements. Authorization to conduct any GPS operation under IFR requires:

a) GPS navigation equipment used for IFR operations must be approved in accordance with the requirements specified in Technical Standard Order (TSO) TSO-C129(), TSO-C196(), TSO-C145(), or TSO-C146(), and the installation must be done in accordance with Advisory Circular AC 20-138(), Airworthiness Approval of Positioning and Navigation Systems. Equipment approved in accordance with TSO-C115a does not meet the requirements of TSO-C129. Visual flight rules (VFR) and hand-held GPS systems are not authorized for IFR navigation, instrument approaches, or as a principal instrument flight reference.

b) Aircraft using un-augmented GPS (TSO-C129() or TSO-C196()) for navigation under IFR must be equipped with an alternate approved and operational means of navigation suitable for navigating the proposed route of flight. (Examples of alternate navigation equipment include VOR or DME/DME/IRU capability). Active monitoring of alternative navigation equipment is not required when RAIM is available for integrity monitoring. Active monitoring of an alternate means of navigation is required when the GPS RAIM capability is lost.

c) Procedures must be established for use in the event that the loss of RAIM capability is predicted to occur. In situations where RAIM is predicted to be unavailable, the flight must rely on other approved navigation equipment, re-route to where RAIM is available, delay departure, or cancel the flight.

d) The GPS operation must be conducted in accordance with the FAA-approved aircraft flight manual (AFM) or flight manual supplement. Flight crew members must be thoroughly familiar with the particular GPS equipment installed in the aircraft, the receiver operation manual, and the AFM or flight manual supplement. Operation, receiver presentation and capabilities of GPS equipment vary. Due to these differences, operation of GPS receivers of different brands, or even models of the same brand, under IFR should not be attempted without thorough operational knowledge. Most receivers have a built-in simulator mode, which allows the pilot to become familiar with operation prior to attempting operation in the aircraft.

e) Aircraft navigating by IFR-approved GPS are considered to be performance-based navigation (PBN) aircraft and have special equipment suffixes. File the appropriate equipment suffix in accordance with Appendix 1, TBL 1-2, on the ATC flight plan. If GPS avionics become inoperative, the pilot should advise ATC and amend the equipment suffix.

f) Prior to any GPS IFR operation, the pilot must review appropriate NOTAMs and aeronautical information. (See GPS NOTAMs/Aeronautical Information).

16.2.2.2 Database Requirements. The onboard navigation data must be current and appropriate for the region of intended operation and should include the navigation aids, waypoints, and relevant coded terminal airspace procedures for the departure, arrival, and alternate airfields.

a) Further database guidance for terminal and en route requirements may be found in AC 90-100, U.S. Terminal and En Route Area Navigation (RNAV) Operations.

b) Further database guidance on Required Navigation Performance (RNP) instrument approach operations, RNP terminal, and RNP en route requirements may be found in AC 90-105, Approval Guidance for RNP Operations and Barometric Vertical Navigation in the U.S. National Airspace System.

c) All approach procedures to be flown must be retrievable from the current airborne navigation database supplied by the equipment manufacturer or other FAA-approved source. The system must be able to retrieve the procedure by name from the aircraft navigation database, not just as a manually entered series of waypoints. Manual entry of waypoints using latitude/longitude or place/bearing is not permitted for approach procedures.

d) Prior to using a procedure or waypoint retrieved from the airborne navigation database, the pilot should verify the validity of the database. This verification should include the following preflight and inflight steps:

1) Preflight:

(a) Determine the date of database issuance, and verify that the date/time of proposed use is before the expiration date/time.

(b) Verify that the database provider has not published a notice limiting the use of the specific waypoint or procedure.

2) Inflight:

(a) Determine that the waypoints and transition names coincide with names found on the procedure chart. Do not use waypoints which do not exactly match the spelling shown on published procedure charts.

(b) Determine that the waypoints are logical in location, in the correct order, and their orientation to each other is as found on the procedure chart, both laterally and vertically.

(c) If the cursory check of procedure logic or individual waypoint location, specified in [b] above, indicates a potential error, do not use the retrieved procedure or waypoint until a verification of latitude and longitude, waypoint type, and altitude constraints indicate full conformity with the published data.

e) Air carrier and commercial operators must meet the appropriate provisions of their approved operations specifications.

1) During domestic operations for commerce or for hire, operators must have a second navigation system capable of reversion or contingency operations.

2) Operators must have two independent navigation systems appropriate to the route to be flown, or one system that is suitable and a second, independent backup system that allows the operator to proceed safely to a suitable airport and complete an instrument approach, and the aircraft must have sufficient fuel (reference 14 CFR 121.349, 125.203, 129.17, and 135.165). These rules ensure the safety of the operation by preventing a single point of failure.

3) The requirements for a second system apply to the entire set of equipment needed to achieve the navigation capability, not just the individual components of the system such as the radio navigation receiver. For example, to use two RNAV systems (e.g., GPS and DME/DME/IRU) to comply with the requirements, the aircraft must be equipped with two independent radio navigation receivers and two independent navigation computers (e.g., flight management systems (FMS)). Alternatively, to comply with the requirements using a single RNAV system with an installed and operable VOR capability, the VOR capability must be independent of the FMS.

4) Due to low risk of disruption or manipulation of GPS signals beyond 50 NM offshore, FAA differentiates between extended and non‐extended overwater operations. To satisfy the requirement for two independent navigation systems:

(a) For all extended over‐water operations (defined in 14 CFR Part 1 as greater than 50 NM from the nearest shoreline), operators may consider dual GPS-based systems to meet the “independent” criteria stipulated by regulation, e.g., §121.349, §135.165.

(b) For all “non‐extended overwater” operations, if the primary navigation system is GPS‐based, the second system must be independent of GPS (for example, VOR or DME/DME/IRU). This allows continued navigation in case of failure of the GPS or WAAS services. Recognizing that GPS interference and test events resulting in the loss of GPS services have become more common, the FAA requires operators conducting IFR operations under 14 CFR 121.349, 125.203, 129.17, and 135.65 to retain a non‐GPS navigation capability, for example either DME/DME, IRU, or VOR for en route and terminal operations, and VOR and ILS for final approach. Since this system is to be used as a reversionary capability, single equipage is sufficient.

16.2.3 Oceanic, Domestic, En Route, and Terminal Area Operations

16.2.3.1 Conduct GPS IFR operations in oceanic areas only when approved avionics systems are installed. TSO-C196 users and TSO-C129 GPS users authorized for Class A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, or C2 operations may use GPS in place of another approved means of long-range navigation, such as dual INS. (See TBL ENR 4.1-4 and TBL ENR 4.1-5.) Aircraft with a single installation GPS, meeting the above specifications, are authorized to operate on short oceanic routes requiring one means of long-range navigation (reference AC 20-138, Appendix 1).

16.2.3.2 Conduct GPS domestic, en route, and terminal IFR operations only when approved avionics systems are installed. Pilots may use GPS via TSO-C129 authorized for Class A1, B1, B3, C1, or C3 operations GPS via TSO-C196; or GPS/WAAS with either TSO-C145 or TSO-C146. When using TSO-C129 or TSO-C196 receivers, the avionics necessary to receive all of the ground-based facilities appropriate for the route to the destination airport and any required alternate airport must be installed and operational. Ground-based facilities necessary for these routes must be operational.

a) GPS en route IFR operations may be conducted in Alaska outside the operational service volume of ground-based navigation aids when a TSO-C145 or TSO-C146 GPS/wide area augmentation system (WAAS) system is installed and operating. WAAS is the U.S. version of a satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS).

1) In Alaska, aircraft may operate on GNSS Q-routes with GPS (TSO-C129 or TSO-C196) equipment while the aircraft remains in Air Traffic Control (ATC) radar surveillance or with GPS/WAAS (TSO-C145 or TSO-C146) which does not require ATC radar surveillance.

2) In Alaska, aircraft may only operate on GNSS T-routes with GPS/WAAS (TSO-C145 or TSO-C146) equipment.

b) Ground-based navigation equipment is not required to be installed and operating for en route IFR operations when using GPS/WAAS navigation systems. All operators should ensure that an alternate means of navigation is available in the unlikely event the GPS/WAAS navigation system becomes inoperative.

c) Q-routes and T-routes outside Alaska. Q-routes require system performance currently met by GPS, GPS/WAAS, or DME/DME/IRU RNAV systems that satisfy the criteria discussed in AC 90-100, U.S. Terminal and En Route Area Navigation (RNAV) Operations. T-routes require GPS or GPS/WAAS equipment.

16.2.3.3 GPS IFR approach/departure operations can be conducted when approved avionics systems are installed and the following requirements are met:

a) The aircraft is TSO-C145 or TSO-C146 or TSO-C196 or TSO-C129 in Class A1, B1, B3, C1, or C3; and

b) The approach/departure must be retrievable from the current airborne navigation database in the navigation computer. The system must be able to retrieve the procedure by name from the aircraft navigation database. Manual entry of waypoints using latitude/longitude or place/bearing is not permitted for approach procedures.

c) The authorization to fly instrument approaches/departures with GPS is limited to U.S. airspace.

d) The use of GPS in any other airspace must be expressly authorized by the FAA Administrator.

e) GPS instrument approach/departure operations outside the U.S. must be authorized by the appropriate sovereign authority.

16.2.4 Departures and Instrument Departure Procedures (DPs)

The GPS receiver must be set to terminal (±1 NM) CDI sensitivity and the navigation routes contained in the database in order to fly published IFR charted departures and DPs. Terminal RAIM should be automatically provided by the receiver. (Terminal RAIM for departure may not be available unless the waypoints are part of the active flight plan rather than proceeding direct to the first destination.) Certain segments of a DP may require some manual intervention by the pilot, especially when radar vectored to a course or required to intercept a specific course to a waypoint. The database may not contain all of the transitions or departures from all runways and some GPS receivers do not contain DPs in the database. It is necessary that helicopter procedures be flown at 70 knots or less since helicopter departure procedures and missed approaches use a 20:1 obstacle clearance surface (OCS), which is double the fixed-wing OCS, and turning areas are based on this speed as well.

16.2.5 GPS Instrument Approach Procedures

16.2.5.1 GPS overlay approaches are designated non-precision instrument approach procedures that pilots are authorized to fly using GPS avionics. Localizer (LOC), localizer type directional aid (LDA), and simplified directional facility (SDF) procedures are not authorized. Overlay procedures are identified by the “name of the procedure” and “or GPS” (e.g., VOR/DME or GPS RWY 15) in the title. Authorized procedures must be retrievable from a current onboard navigation database. The navigation database may also enhance position orientation by displaying a map containing information on conventional NAVAID approaches. This approach information should not be confused with a GPS overlay approach (see the receiver operating manual, AFM, or AFM Supplement for details on how to identify these approaches in the navigation database).

16.2.5.2 Stand-alone approach procedures specifically designed for GPS systems have replaced many of the original overlay approaches. All approaches that contain “GPS” in the title (e.g., “VOR or GPS RWY 24,” “GPS RWY 24,” or “RNAV (GPS) RWY 24”) can be flown using GPS. GPS-equipped aircraft do not need underlying ground-based NAVAIDs or associated aircraft avionics to fly the approach. Monitoring the underlying approach with ground-based NAVAIDs is suggested when able. Existing overlay approaches may be requested using the GPS title; for example, the VOR or GPS RWY 24 may be requested as “GPS RWY 24.” Some GPS procedures have a Terminal Arrival Area (TAA) with an underlining RNAV approach.

16.2.5.3 For flight planning purposes, TSO-C129 and TSO-C196-equipped users (GPS users) whose navigation systems have fault detection and exclusion (FDE) capability, who perform a preflight RAIM prediction for the apprach integrity at the airport where the RNAV (GPS) approach will be flown, and have proper knowledge and any required training and/or approval to conduct a GPS-based IAP, may file based on a GPS-based IAP at either the destination or the alternate airport, but not at both locations. At the alternate airport, pilots may plan for:

a) Lateral navigation (LNAV) or circling minimum descent altitude (MDA);

b) LNAV/vertical navigation (LNAV/VNAV) DA, if equipped with and using approved barometric vertical navigation (baro-VNAV) equipment;

c) RNP 0.3 DA on an RNAV (RNP) IAP, if they are specifically authorized users using approved baro-VNAV equipment and the pilot has verified required navigation performance (RNP) availability through an approved prediction program.

16.2.5.4 If the above conditions cannot be met, any required alternate airport must have an approved instrument approach procedure other than GPS-based that is anticipated to be operational and available at the estimated time of arrival, and which the aircraft is equipped to fly.

16.2.5.5 Procedures for Accomplishing GPS Approaches

a) An RNAV (GPS) procedure may be associated with a Terminal Arrival Area (TAA). The basic design of the RNAV procedure is the “T” design or a modification of the “T” (See ENR 1.5, Paragraph 12.4, Terminal Arrival Area (TAA), for complete information).

b) Pilots cleared by ATC for an RNAV (GPS) approach should fly the full approach from an Initial Approach Waypoint (IAWP) or feeder fix. Randomly joining an approach at an intermediate fix does not assure terrain clearance.

c) When an approach has been loaded in the navigation system, GPS receivers will give an “arm” annunciation 30 NM straight line distance from the airport/heliport reference point. Pilots should arm the approach mode at this time if not already armed (some receivers arm automatically). Without arming, the receiver will not change from en route CDI and RAIM sensitivity of ±5 NM either side of centerline to ±1 NM terminal sensitivity. Where the IAWP is inside this 30 mile point, a CDI sensitivity change will occur once the approach mode is armed and the aircraft is inside 30 NM. Where the IAWP is beyond 30 NM from the airport/heliport reference point and the approach is armed, the CDI sensitivity will not change until the aircraft is within 30 miles of the airport/heliport reference point. Feeder route obstacle clearance is predicated on the receiver being in terminal (±1 NM) CDI sensitivity and RAIM within 30 NM of the airport/heliport reference point; therefore, the receiver should always be armed (if required) not later than the 30 NM annunciation.

d) The pilot must be aware of what bank angle/turn rate the particular receiver uses to compute turn anticipation, and whether wind and airspeed are included in the receiver's calculations. This information should be in the receiver operating manual. Over or under banking the turn onto the final approach course may significantly delay getting on course and may result in high descent rates to achieve the next segment altitude.

e) When within 2 NM of the Final Approach Waypoint (FAWP) with the approach mode armed, the approach mode will switch to active, which results in RAIM and CDI changing to approach sensitivity. Beginning 2 NM prior to the FAWP, the full scale CDI sensitivity will smoothly change from ±1 NM to ±0.3 NM at the FAWP. As sensitivity changes from ±1 NM to ±0.3 NM approaching the FAWP, with the CDI not centered, the corresponding increase in CDI displacement may give the impression that the aircraft is moving further away from the intended course even though it is on an acceptable intercept heading. Referencing the digital track displacement information (cross track error), if it is available in the approach mode, may help the pilot remain position oriented in this situation. Being established on the final approach course prior to the beginning of the sensitivity change at 2 NM will help prevent problems in interpreting the CDI display during ramp down. Therefore, requesting or accepting vectors which will cause the aircraft to intercept the final approach course within 2 NM of the FAWP is not recommended.

f) When receiving vectors to final, most receiver operating manuals suggest placing the receiver in the non-sequencing mode on the FAWP and manually setting the course. This provides an extended final approach course in cases where the aircraft is vectored onto the final approach course outside of any existing segment which is aligned with the runway. Assigned altitudes must be maintained until established on a published segment of the approach. Required altitudes at waypoints outside the FAWP or stepdown fixes must be considered. Calculating the distance to the FAWP may be required in order to descend at the proper location.

g) Overriding an automatically selected sensitivity during an approach will cancel the approach mode annunciation. If the approach mode is not armed by 2 NM prior to the FAWP, the approach mode will not become active at 2 NM prior to the FAWP, and the equipment will flag. In these conditions, the RAIM and CDI sensitivity will not ramp down, and the pilot should not descend to MDA, but fly to the MAWP and execute a missed approach. The approach active annunciator and/or the receiver should be checked to ensure the approach mode is active prior to the FAWP.

h) Do not attempt to fly an approach unless the procedure in the onboard database is current and identified as “GPS” on the approach chart. The navigation database may contain information about non-overlay approach procedures that enhances position orientation generally by providing a map, while flying these approaches using conventional NAVAIDs. This approach information should not be confused with a GPS overlay approach (see the receiver operating manual, AFM, or AFM Supplement for details on how to identify these procedures in the navigation database). Flying point to point on the approach does not assure compliance with the published approach procedure. The proper RAIM sensitivity will not be available and the CDI sensitivity will not automatically change to ±0.3 NM. Manually setting CDI sensitivity does not automatically change the RAIM sensitivity on some receivers. Some existing non-precision approach procedures cannot be coded for use with GPS and will not be available as overlays.

i) Pilots should pay particular attention to the exact operation of their GPS receivers for performing holding patterns and in the case of overlay approaches, operations such as procedure turns. These procedures may require manual intervention by the pilot to stop the sequencing of waypoints by the receiver and to resume automatic GPS navigation sequencing once the maneuver is complete. The same waypoint may appear in the route of flight more than once consecutively (for example, IAWP, FAWP, MAHWP on a procedure turn). Care must be exercised to ensure that the receiver is sequenced to the appropriate waypoint for the segment of the procedure being flown, especially if one or more fly-overs are skipped (for example, FAWP rather than IAWP if the procedure turn is not flown). The pilot may have to sequence past one or more fly-overs of the same waypoint in order to start GPS automatic sequencing at the proper place in the sequence of waypoints.

j) Incorrect inputs into the GPS receiver are especially critical during approaches. In some cases, an incorrect entry can cause the receiver to leave the approach mode.

k) A fix on an overlay approach identified by a DME fix will not be in the waypoint sequence on the GPS receiver unless there is a published name assigned to it. When a name is assigned, the along track distance (ATD) to the waypoint may be zero rather than the DME stated on the approach chart. The pilot should be alert for this on any overlay procedure where the original approach used DME.

l) If a visual descent point (VDP) is published, it will not be included in the sequence of waypoints. Pilots are expected to use normal piloting techniques for beginning the visual descent, such as ATD.

m) Unnamed stepdown fixes in the final approach segment may or may not be coded in the waypoint sequence of the aircraft's navigation database and must be identified using ATD. Stepdown fixes in the final approach segment of RNAV (GPS) approaches are being named, in addition to being identified by ATD. However, GPS avionics may or may not accommodate waypoints between the FAF and MAP. Pilots must know the capabilities of their GPS equipment and continue to identify stepdown fixes using ATD when necessary.

16.2.5.6 Missed Approach