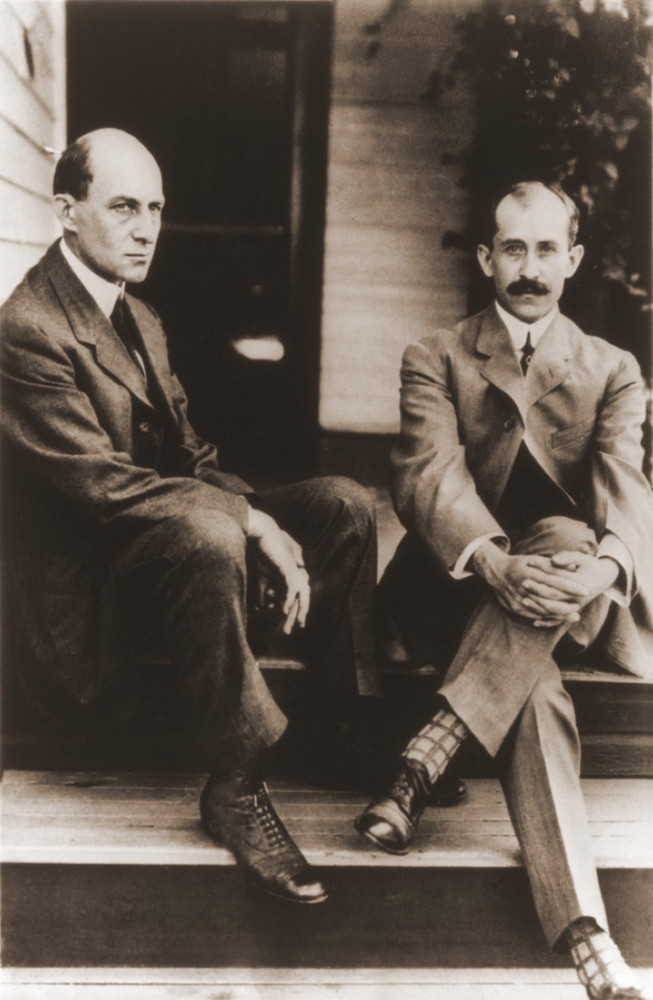

A Legacy of Greatness

How the Wright Brothers Transformed Our World

At the dawn of the 20th century, the scientific community and broader public believed with near certainty that the human flight barrier was real. Indeed, on Christmas Eve 1897 The Washington Post, a newspaper now owned by the owner of a rocket company, declared, “It is a fact that man can’t fly.”

The prior year, however, in Dayton, Ohio, a childhood interest in the possibilities of flight that began with a toy helicopter was reawakened in Wilbur Wright. The 29-year-old bicycle mechanic was reading about the flight experiments of German glider enthusiast Otto Lilienthal and shared what he learned with his brother and business partner Orville, 25. It lit a spark in their minds. In a little over seven years, the brothers, who lacked high school diplomas, were to upend the realm of possibility.

Here are some highlights of their epic quest to invent, build and fly the world’s first airplane.

They Hit the Books

Wilbur wrote the Smithsonian Institution on May 30, 1899, requesting materials on “the problem of mechanical and human flight,” stating, “I am an enthusiast, but not a crank in the sense that I have some pet theories as to the proper construction of a flying machine.” The brothers devoured books and pamphlets the Smithsonian sent them, including the writings of Samuel Pierpont Langley, the Institution’s secretary, who would mount a well-funded effort to achieve flight with his “Great Aerodrome,” and Octave Chanute, a civil engineer who conducted pathbreaking glider experiments and came to serve the brothers as a valued advisor.

They Solved Essential Problems

The brothers created a three-axis control system, which enabled the pilot to steer the aircraft and maintain its equilibrium. To achieve accurate measurements of the “lift” and “drag” of a wing’s surface they designed and built a small-scale wind tunnel that tested 38 wing surfaces, setting the “balances” or “airfoils” of different shaped hacksaw blades at angles from 0 to 45 degrees in winds up to 27 miles per hour. With little literature to rely on, they designed the aircraft’s propellers. And to improve the controllability of their flyer, Orville came up with the idea of making the rear rudder movable, with Wilbur proposing to simplify the pilot’s job by connecting control of the rudder with those of the wing warping.

Thank the Weather Bureau for Kitty Hawk

The brothers recognized that a location with sufficient wind of about 15 miles per hour was necessary to conduct flight experiments. Octave Chanute suggested the coasts of South Carolina or Georgia. After receiving U.S. Weather Bureau records about prevailing winds around the country, they selected Kitty Hawk, a remote spot on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. In September 1900 they brought to Kitty Hawk their first flight vehicle, a glider whose parts were valued at $15.

Bird Watching Was More than a Hobby

Wilbur was convinced there was much to learn from the flight of birds, and at Kitty Hawk carefully studied the movements of eagles, snow-white gannets, hawks, pigeons and turkey vultures. He applied these observations to the “wing warping” that enabled the Wright Flyer to bank and turn.

It Was a Coin Flip into History

Wilbur won a coin flip to pilot the Wright Flyer on their first powered flight attempt from Kill Devil Hills (four miles south of Kitty Hawk) on Dec. 14, 1903. Because Wilbur pulled too hard on the rudder, the Flyer surged upward at a steep angle, and he brought it down abruptly. Following minor repairs, Orville got the honor of piloting the Flyer into history the icy cold morning of Dec. 17.

A Beekeeping Journal Got the Real Scoop

The first newspaper articles about the Wright Brothers’ flight were secondhand accounts and largely inaccurate. The first complete account of the Wright Brother’s accomplishments, focusing on their subsequent flights at Huffman Prairie near their home in Dayton, appeared in the Jan. 1,1905, issue of Gleanings in Bee Culture. The author was Amos Root, a curious beekeeper from Medina, Ohio who befriended the brothers.

How Tragedy Struck

On Sept. 17, 1908, Orville piloted a demonstration of a new version of the Wright Flyer for the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia. A broken propeller blade caused the airplane to lose control, resulting in a crash that killed passenger Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge. Selfridge was aviation’s first casualty. Orville was also seriously injured with a broken left femur, several broken ribs, and a damaged hip.

He Buzzed Lady Liberty

Wilbur’s last flights occurred in late September and early October 1909 with large crowds in lower Manhattan cheering his trips around New York Harbor and the Hudson River and circling the Statue of Liberty. Perched beneath his wing was a red canoe in the event of an emergency water landing. Fortunately, no miracle on the Hudson was required.

It took a While for the Wright Flyer to Find a Home

The Wright Brothers had a long-running dispute with the Smithsonian Institution, which had asserted Langley’s “Great Aerodrome” was the “first man-carrying flying machine capable of sustained flight.” After the Smithsonian’s leader Charles Walcott turned down the Wright Brothers’ offer to house the 1903 Flyer, Orville sent the airplane on loan to London’s Science Museum in 1928. Twenty years later, this national treasure finally returned to U.S. soil and was placed in the Smithsonian, shortly after Orville, the last surviving Wright Brother, passed away.

Sources: David McCullough, “The Wright Brothers”

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Wright Brothers Gallery