No Fowl Play: How Wildlife Strike Mitigation Helps Ensure Safe Skies

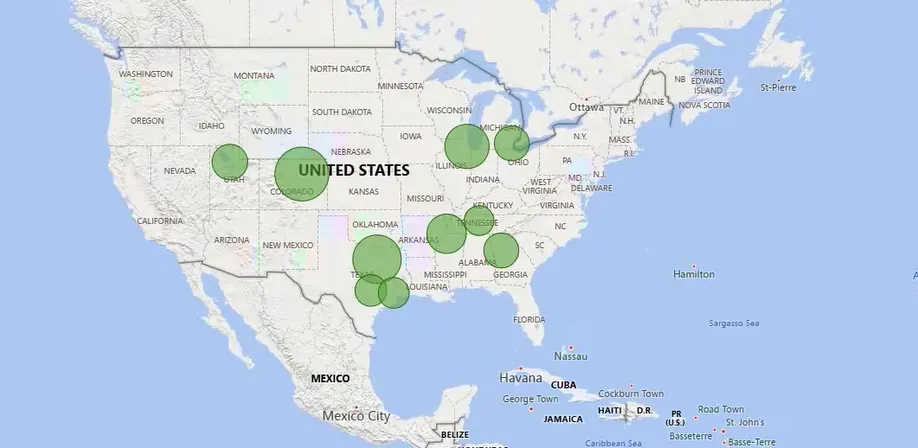

If a picture is worth a thousand words, the National Wildlife Strike Database can tell an important and compelling safety story.

Visual depictions of wildlife strikes from the database support trend analysis that informs FAA guidance for mitigating them, which helps keep the flying public safe and wildlife out of harm’s way.

“Whatever happens out in the field, we can see the trends here in the strike database,” said John Weller, the chief biologist in the FAA’s airports organization. “While it may be a different species elsewhere, we know what species groups are the most hazardous to planes. We know when they create the greatest risk, what time of day, what phase of flight, their migratory patterns, behavior and attractants.”

With more than three decades of expertise in this area, the United States has long been a global leader.

“Every country that I’ve talked to uses the U.S. strike database as their gold standard,” Weller said.

The modern approach to addressing wildlife strikes began in the 1990s when the FAA and U.S. Department of Agriculture partnered to systematically analyze and publish all strike data and co-authored the first manual for wildlife hazard management at airports. The comprehensive strike report and manual established the agencies as leaders in wildlife hazard management and were used at airports throughout North America, Europe, Africa and South America.

Avian Allies in Aviation

Domestically, the FAA and USDA established a National Wildlife Strike Database in 1994 to centralize their data collection. Since then, it has received more than 300,000 strike submissions including 22,372 in 2024.

Strike reporting is voluntary and relies on the airport operators, pilots, air traffic controllers, airline mechanics, biologists and other airport grounds personnel to provide the incident details. USDA scientists analyze and filter the data to identify trends, which helps the FAA and airports identify hazardous species and effective mitigation strategies.

The FAA has issued approximately $400 million in Airport Improvement Program (AIP) grants for mitigation projects including upgraded airfield perimeter fencing, wildlife hazard assessments and plans, pyrotechnic launchers, infrared cameras and even canine patrol programs.

Mitigation Strategies: A High-Flying Success

All of this work has yielded positive results.

The average body mass of reported bird strikes decreased by 64 percent between 2000 to 2024. Strikes that cause damage have also decreased, from 6 percent of all strikes in 1996 to 3.7 percent in 2024.

“The data shows that strikes may happen every day, but damaging strikes remain rare events because of the research, analysis and mitigation strategies we implement and recommend, both domestically and internationally,” Weller said.

More innovative mitigations are on the horizon. The use of long-range systems such as remote automated surveillance systems (e.g., avian radars and infrared/electro-optical systems) which extend out to 5 miles, allow for real-time detection and monitoring of animals on and near airports. The Foreign Object Debris (FOD) radars provide a secondary monitoring benefit for wildlife on the ground.

Unmanned Aerial Systems (better known as drones) continue to be a significant tool, on and near airport environments. They are effective in areas with difficult access (e.g., large bodies of water, rough terrain, etc.) and can fly predetermined routes to detect, disperse and monitor hazardous wildlife.

FAA’s International Influence

Foreign aviation regulators often turn to the FAA for advice. Last year, the Kenyan government asked the FAA to provide a multi-day wildlife hazard management workshop that brought together experts and stakeholders from nine countries.

The FAA’s Wildlife Hazard Mitigation program team delivered presentations on topics including developing a wildlife hazard management program, detecting and monitoring wildlife, and dealing with unique/protected species. The goal is to ensure that the level of safety worldwide is as universal and fundamental as air travel itself.

Weller also was asked to lead the team that’s updating the International Civil Aviation Organization bird strike manual, which is a guide for regulators worldwide.

“While our focus is domestic, it’s experiences like this and sharing our findings that help make a difference in aviation safety all around the world,” Weller said. “That’s why we share what we do. It’s for the benefit of everybody.”