McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61

Photo copyright Sam Chui - used with permission

Fine Air Flight 101, N27UA

Miami, Florida

August 7, 1997

Fine Airlines Services, Inc., (Fine Air) Flight 101, a McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61 was a cargo flight, scheduled from Miami, Florida to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on August 7, 1997. During takeoff from runway 27R at Miami International Airport, after becoming airborne, the airplane pitched up sharply, reaching an altitude of approximately 600 feet. Witnesses stated that the airplane achieved a nose up attitude of approximately 70 degrees before apparently stalling and then crashing. The three flight crew members and one security guard on board were killed, and a motorist was killed on the ground. The airplane was destroyed by impact and a post-crash fire.

The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable cause of the accident was an incorrect loading of cargo that resulted in an aft airplane center of gravity, and a correspondingly incorrect stabilizer trim setting, precipitating an extreme pitch-up at rotation. The improper loading was the direct result of (1) the failure of Fine Air to exercise operational control over the cargo loading process; and (2) the failure of Aeromar (the cargo loader) to load the airplane as specified by Fine Air. Investigators also concluded that factors contributing to the accident were the failure of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to adequately monitor Fine Air’s operational control responsibilities for cargo loading, and the failure of the FAA to ensure that known cargo related deficiencies were corrected at Fine Air.

History of Flight

Photo copyright Alan Rossmore - used with permission

Fine Air Flight 101, a McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61, was a scheduled cargo flight from Miami International Airport (MIA), Miami, Florida, to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The flight had originally been scheduled for a 0915 Eastern Standard Time (EST) departure with a different airplane. However, the intended airplane was delayed en route, so the accident airplane was scheduled as a replacement. The accident airplane N27UA arrived at MIA at approximately 0930 and was parked at the Fine Air ramp.

Flight 101 was scheduled to carry cargo for Aeromar C por A (Aeromar), a Dominican Republic corporation operating out of Miami. The first cargo pallet was loaded onto the accident airplane shortly before 1000, and the crew was notified to arrive for a 1200 departure. Following crew arrival, and a preflight inspection performed by the flight engineer, the crew started engines, and requested taxi clearance at approximately 1230. The airplane was cleared to taxi to runway 27R, and during the one-minute taxi, the crew performed control checks. At 1234:31, the flight was cleared for takeoff, and the airplane began its takeoff roll at 1235. The investigation determined, via the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), that the first officer was flying the airplane.

Photo copyright Aad Rehorst - used with permission

During takeoff rotation, the CVR recorded the captain saying, "easy, easy, easy easy," in response to what the investigators later concluded was a more rapid than normal rotation, resulting from the airplane's extreme aft loading, and an incorrect stabilizer trim setting. Seven seconds later, following liftoff, the first officer called, "gear up," followed almost immediately by, "what's going on?" Within one second the sound of the stabilizer trim in motion was recorded, rapidly followed by the sound of the stick shaker (stall warning). Over the next seven seconds, the stabilizer trim was used multiple times, as recorded on the CVR, in what the investigators concluded were attempts to trim the airplane nose down and help correct an increasing pitch attitude. The stick shaker briefly stopped approximately 14 seconds after the "gear up" call, but was reinitiated 5.8 seconds later, and continued until impact.

A Fine Air captain who witnessed the accident stated that takeoff rotation was "not smooth," and that after the airplane became airborne, it attained an extreme pitch attitude, making it possible to see the tops of the wings and fuselage. An MIA tower controller stated that after rotation the airplane pitched up to approximately 70 degrees before the nose dropped. He stated that the airplane crashed in a tail first attitude with the right wing slightly low.

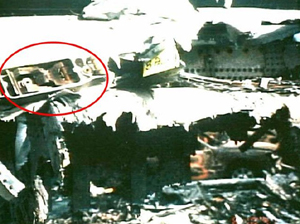

The airplane crashed at 1236:25.4, approximately 30 seconds after lifting off. The airplane crashed about 3000 feet west of the departure end of runway 27R. Wreckage extended roughly along the extended runway centerline for 575 feet beyond the initial point of impact. The four people on board the airplane, and one person on the ground were killed. The airplane was destroyed by impact and post-crash fire.

Photo copyright Aad Rehorst - used with permission

Fine Air and Aeromar

On November 10, 1992, Fine Airline Services, Inc. (Fine Air) received FAA authorization to operate under 14 CFR part 119.21 as a supplemental cargo carrier, and further to operate under 14 CFR part 121. The company was incorporated in 1989 to provide cargo services between the United States and the Central America and Caribbean regions. At the time of the accident, Fine Air had a "wet lease" agreement with Aeromar, a freight forwarding company. Aeromar was established in 1968, and had offices in Miami, and Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

In May 1997, Fine Air and Aeromar signed a "wet lease" agreement, under which Fine Air agreed to carry Aeromar's freight. Aeromar agreed to "provide fuel, loading and unloading at all stops, landing fees, duties, permits, over flight, taxes, parking fees.... ground handling and all other flight related expenses." The agreement further specified that Fine Air would maintain operational control of the aircraft at all times, and Fine Air would utilize their own flight crewmembers. Training and airplane maintenance would be conducted under Fine Air; and servicing of the aircraft would be done under the supervision of Fine Air employees. Aircraft dispatch functions were also to be performed by Fine Air personnel.

In October 1997, in a letter to Fine Air, the FAA characterized the "wet lease" agreements as transportation agreements, perhaps even charter agreements, but reiterated that since Fine Air intended to operate under 14 CFR part 121, no aspect of operational control could be negotiated away from Fine Air. The letter further stated that " the loading of cargo as it relates to weight and balance requirements, cargo restraint requirements and hazardous materials requirements, is an aspect of operational control and must be under the control of, and be the responsibility of, Fine Air Services, Inc."

Results of inspections, one conducted by the Department of Defense, and another by the FAA, noted a number of discrepancies in Fine Air's operations. Most notably, as related to this accident, the FAA found discrepancies with regard to weight and balance procedures. The inspection determined that Fine Air had "no standards and schedules for the calibration of commercial scales used to determine cargo weights at Miami" and "loading schedules instructions...do not include instruction for calculation of weight and balance." The FAA inspection team also determined that Fine Air manuals did not "include procedures for weighing aircraft required by 14 CFR Part 121.135(b)(20)."

– From NTSB Accident Report

View Larger

Cargo Loading

For normal operations, actual loading of cargo was performed and supervised by Aeromar personnel. At the time of the accident, for operations conducted at Miami, Fine Air personnel did not actively, or regularly, participate in supervision of cargo loading. Fine Air did perform the weight and balance calculations associated with a given flight, and transmitted the loading information to Aeromar, but did not verify that the airplane was loaded in accordance with the transmitted loading instructions. Per Fine Air operational procedures, the flight engineer was responsible to verify the loading and weight and balance of the airplane, and to verify that at least three pallet locks were engaged in an occupied position. During the investigation, a Fine Air representative acknowledged however, that it would be considered unusual for a flight engineer to perform this inspection during routine operations in Miami. This was considered an action more related to "outstation" operation, at locations other than Miami.

Aeromar loading personnel did not receive any classroom training, but rather were trained by participating in actual aircraft loading. Investigators concluded that this was an effective method of training relative to the physical loading of the airplane but concluded that the significance of effects that cargo loading, and distribution could have on airplane center of gravity, and consequently on airplane handling characteristics, were not understood by loading personnel. Flight 101 had originally been scheduled for another airplane. The intended airplane, N30UA was delayed en route, and would not arrive in time for its scheduled departure as flight 101. Aeromar therefore requested another airplane. Fine Air substituted the accident airplane, N27UA, and rescheduled the departure. This change of airplanes required a series of significant paperwork changes to accommodate the different airplane. Original loading documents for N30UA had stated a cargo weight of 87, 923 pounds, an airplane Center of Gravity (CG) of 30 percent of Mean Aerodynamic Chord (MAC), and a corresponding takeoff trim setting of 2.4 units airplane nose up (ANU). Pallet positions 2 and 17 were scheduled to be empty. To accommodate the weight limitations for N27UA, the replacement airplane, which was slightly heavier than N30UA, weight and balance calculations were redone, and the pallet loading sequence was modified to provide a takeoff CG of 30 percent for the replacement airplane. The modified pallet loading sequence required moving the pallet in position 13 to position 17 and leaving position 13 vacant. Additionally, 1000 pounds of weight needed to be removed from position 10. Fine Air stated that the redefined load sheet was faxed to Aeromar, but the investigation could find no evidence that the Aeromar security guard, who was responsible for the cargo, picked up, or was aware of, the revised paperwork. As a result, investigators determined that the replacement airplane, N27UA, was originally loaded per the instructions intended for N30UA.

Photo copyright Steven Fox - used with permission

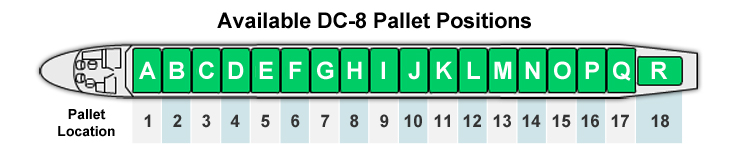

The accident airplane was equipped with a cargo handling system intended to accommodate eighteen 88 by 125-inch pallets. Palletized cargo was loaded through the cargo door in the front of the fuselage via a hydraulic lift and conveyor system to move pallets into the airplane. Once inside the cargo door, the pallets move on a "ball mat," which is a floor mounted device containing roller balls that allow the cargo to be rotated in any direction. Aft of the ball mat, a pallet retention system (floor locks) was installed to provide restraint for palletized cargo.

The cargo floor was configured with five guide tracks, with encased roller bearings to ease movement of cargo pallets forward or aft of the main cargo door. Retractable pallet locks, referred to as "bear traps" were installed at 89-inch intervals along the guide tracks. Each of the 85 pallet locks included a folding lock mechanism, allowing pallets to move over them, and were comprised of both a forward, and aft pawl, in order to restrain cargo both forward and aft of the locking mechanism. When raised, and locked in position, the locks engage the edges of adjoining cargo pallets and provide both longitudinal and vertical restraint. Additional rails were installed along the cabin walls to prevent cargo contacting the sidewalls of the airplane fuselage. The loading system was designed such that pallets 1 through 17 were to be loaded with the 88-inch dimension longitudinal to the fuselage, and pallet 18, since it would be installed in the tapering portion of the aft fuselage would be rotated 90 degrees such that the 125-inch dimension was longitudinal. A video illustrating the functioning of the cargo locks is available below:

On the accident flight, the cargo was cut denim material that was delivered to the Aeromar warehouse by a freight transfer agent. Shipping documents indicated that the cargo weighed 89,719 pounds. The cargo was weighed after arriving at the Aeromar warehouse, and again after having been palletized. The initial weighing confirmed the weight listed on the shipping documents, and the second weighing listed the weight as 88923 pounds.

According to the accident report, about 39000 pounds of cargo arrived in rectangular polyethylene wrapped containers known as "big paks," and the remaining approximately 51000 pounds was contained in boxes. All of the cargo was loaded onto pallets, in preparation for loading onto the accident airplane. Four big paks were arranged onto a pallet, and two more were stacked on top of these. The pallets themselves were large, flat metal sheets, resembling a "cookie sheet." This entire arrangement was then wrapped in black plastic, and secured to the pallet with netting, which was roped to the corners of the pallet. The boxed cargo had also been loaded onto pallets at the Aeromar warehouse.

Photo copyright Marlo Plate - used with permission

In information conveyed to the investigators, it was stated that the cargo weight did not include the weight of each metal pallet, covering, or netting. Because of this oversight, the weight of the payload was incorrect by as much as 4,400 lbs.

The cargo loading process involved five "loaders," a loading supervisor, and a security guard. A Fine Air supervisor was also present, but was driving a forklift, and not functioning in a supervisory capacity. The Aeromar loading supervisor told investigators that he was responsible for managing the loading process and ensuring that all pallet locks were in place when the loading was complete. The security guard was responsible to mark the pallets with their assigned position, and to tell the loaders where to position each pallet. The security guard had the weight and balance information as computed for the flight, although investigators determined that he may not have picked up revised loading instructions transmitted to Aeromar when the load was recalculated for the replacement airplane. Pallets were individually identified by letter, "A" through "P," in this case, and then identified by number for their position on the airplane. For example, pallet "A" was identified to be placed in position 18, the most aft location.

Photo copyright Steve Fox - used with permission

A pallet was loaded into position 18 (the aft end of the cargo compartment), and position 17 was left vacant. The pallet locks were placed up in front of position 17, and pallets were loaded forward of that position. The loading supervisor told investigators that as subsequent pallets were loaded, the pallet locks could not be extended. This was the result of cargo extending beyond the edges of the pallets, preventing the pallets from fitting snugly against each other, and interfering with the pallet locks. An examination by the loading supervisor determined that pallets locks were not engaged on pallet positions 3 through 10. Three pallets were removed and following a conversation between the Aeromar loading supervisor and the Fine Air supervisor; the Fine Air supervisor told the loaders to move everything aft such that the vacant position 17 was occupied. He also told them to turn pallet 4 around. Investigators determined that, based on statements from the Fine Air supervisor, he had intended that pallet 4 be rotated 180 degrees, enabling engagement of the pallet locks, but his order was misinterpreted, and the pallet was only rotated 90 degrees. This pallet, which now occupied all of position 5, and part of position 4, was then tied down and secured with snap rings, and the locks were engaged at the forward end of the pallet.

View Larger

Following the loading of the cargo, investigators determined, based on statements from the Fine Air supervisor that pallet positions 1 and 3 were occupied, and the locks were engaged. Pallet position 2 was empty. The pallet in position 4 was rotated 90 degrees from its intended position, and all other positions aft of pallet 4 were occupied, including position 17, which was specified in loading instructions to be empty. Thus, the final loading did not reflect either of the planned loads for N30UA or N27UA.

Following the accident, investigators found "considerable evidence" that few of the cargo locks were engaged. Sixty cargo locks (of the 85 installed) were recovered, and of those 60, 57 were found in the unlocked position, and there was no evidence that locks had failed during the accident.

Weight and Balance

The NTSB accident report listed the weight and balance for Flight 101 as follows:

Basic Operating Weight: 145,949 pounds

Cargo Weight: 87,823 pounds

Zero Fuel Weight: 233,982 pounds

Maximum Zero Fuel Weight: 234,000 pounds

Takeoff Fuel: 48,500 pounds

Gross Takeoff Weight: 282,482 pounds

Maximum Takeoff Weight (Runway 27R): 315,400 pounds

Maximum Landing Weight: 252,000 pounds

Fuel Burn to SDQ: 31,875 pounds

Center of Gravity: 30.0 percent mean aerodynamic chord (MAC)

Aft CG Limit: 33.1 percent MAC

Stabilizer trim setting: 2.4 units

Takeoff Flap Setting: 15 degrees

Photo copyright Carsten Bauer - used with permission

Investigators determined that the load sheet for the accident airplane contained a number of errors. Following the accident, it was determined that the weight listed for the pallet in position 17 was low by 100 pounds. Further, load calculations accounted for 1000 pounds of weight that was supposed to have been removed from the pallet in position 10, but, in fact, was not removed. Therefore, the cargo weight should have been 88923 pounds, rather than the 87823 pounds that was used in the weight and balance calculations.

It was also determined that the load sheet used for the accident airplane was for a DC-8-62/63. The accident airplane was a DC-8-61. This error resulted in an airplane center of gravity that was farther forward than shown on the load sheet. Also, according to investigators, the weight for the pallet in position 18 (the most aft) was listed as 6088 pounds. Post-accident calculations revealed that the maximum weight at this position should not have exceeded 3780 pounds.

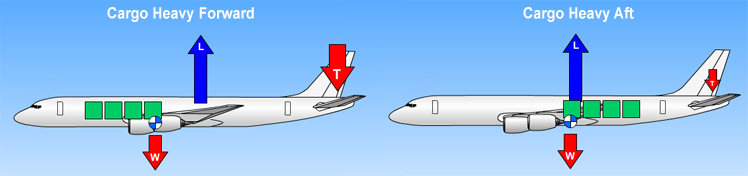

Based on testimony from the cargo loaders, the investigation determined that the accident airplane had originally been loaded per the plan specified for the originally designated airplane (N30UA), with positions 2 and 17 empty. Based on testimony, a second loading scenario was developed by the investigation. Relative to the intended loading configuration, pallets in position 5 and aft were moved back one position, thereby occupying position 17. Pallet 4 was rotated 90 degrees, and pushed back into position 5, overlapping into part of position 4. This assumed scenario also included 6950 pounds loaded onto the pallet in position 10 (including 1000 pounds that had not been removed). This loading resulted in a calculated CG of 32.4 percent MAC. The addition of 275 pounds (4400 pounds total) per pallet, to account for the weights of the pallet, and packing materials, moved the CG slightly further aft to 32.7 percent MAC. With an assumed cargo weight of 88, 923 pounds, moving 13 pallets aft, and rotating pallet 4, the CG moved aft from 24 percent MAC with a recommended takeoff trim setting of 5.4 units ANU, to 32.4 percent MAC requiring a trim setting of 1.0-unit ANU. Assuming a cargo weight of 94119 pounds, which accounted for the additional weight of packing material on each pallet, the calculated CG became 32.8 percent MAC, requiring a trim setting of .9 units ANU. When correctly set, the stabilizer trim setting will cause the airplane to be "in trim," requiring very little pilot control force, at a specific, scheduled airspeed following liftoff. An animation illustrating the effects of various cargo loadings and the flight path of the airplane after takeoff is available below:

In 2011, the Ground Handling Operations Safety Team (GHOST), a British Civil Aviation Authority (CAA)/industry group committed to develop strategies to mitigate the safety risks from aircraft ground handling and ground support activities, released a video titled "Safety in the Balance." The video explains airplane loading, and the critical effects that weight and balance can have on flight safety. The 21-minute video is available below:

Horizontal Stabilizer Trim

Photo copyright Edward Kehler - used with permission

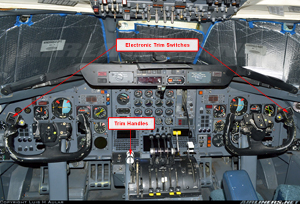

The horizontal stabilizer is an inverted airfoil providing a counteracting force to the wing lift and pitching moments, and the aircraft weight. The horizontal stabilizer balances the forces to maintain a desired pitch attitude or speed. The horizontal stabilizer is composed of two main components, the trimmable stabilizer, and elevator. The stabilizer is moved by an electrical switch on either pilot's control wheel, or alternatively, by a pair of handles, known as "suitcase handles," due to their resemblance, located next to the captain's seat. The stabilizer position (trim setting) is also indicated next to the captain's seat. When trimming the airplane, the horizontal stabilizer is moved by an electric motor, attached to a jack screw.

Training Manual Description of DC-8 Trim Controls- illustration

The terms center of lift and center of gravity are commonly used to reference locations where lift and weight are acting. The center of gravity will move forward or aft over a small range as fuel is used. The center of lift can move forward or aft due to changes in lift resulting from speed or weight changes (fuel burn). Additionally, the center of lift moves aft as Mach number increases. On swept wing aircraft, due to the wing sweep, the center of lift and center of gravity have a greater range of movement. This in turn requires a larger balancing force from the horizontal stabilizer. The effects of various loading schemes on airplane center of gravity and horizontal stabilizer position are illustrated in the following animation below:

Airplane Handling Characteristics and Flight Crew Actions

Following the accident, the NTSB conducted a series of piloted simulations intended to evaluate airplane handling characteristics throughout the range of weights and centers of gravity that may have existed for the accident flight. Test results at a CG of 33 percent MAC suggested that the airplane retained sufficient control authority to prevent the pitch up and stall. AT 35 percent MAC, events progressed much more rapidly, and though sufficient control authority was available to control or prevent the pitch up and stall, pilot action was required to be immediate. Pilots in the simulation exercises commented that their efforts to control the airplane were successful largely because they were anticipating the pitch up characteristics. Test conditions at CG positions aft of 35 percent MAC exhibited increasing early rotation and pitch up characteristics, not representative of the flight recorder data. Based on comparison with flight recorder data, investigators concluded that the CG at takeoff was near, or even slightly aft of the aft limit of 33.1 percent MAC.

Photo copyright Luis H Aular – used with Permission

View Larger

Weight and balance information provided to the flight crew listed an airplane center of gravity at 30 percent MAC, based on the load plan prepared by dispatchers. Considering another loading scenario, resulting from testimony of Aeromar cargo loaders, Fine Air personnel, and documented pallet weights, investigators calculated a takeoff CG of 32.8 percent MAC. Investigators also noted that a relatively small addition to, or redistribution of cargo could have moved the CG aft of the 33.1 percent aft limit. The numerous loading errors, and errors in documentation, made it impossible for investigators to precisely determine the weight and CG at takeoff. The cargo weight of 88,923 pounds could actually have been as high as 94,119 pounds, 5,196 pounds heavier than listed on the airplane load sheet. Depending on the weight distribution in the cargo compartment, this could have had a significant effect on airplane handling characteristics during takeoff.

Investigators concluded that the flight crew recognized a problem in the airplane pitch response almost immediately upon rotation. A CG position more aft than calculated, in combination with a trim setting based on a more forward CG (trim setting would be more nose up than necessary) would exacerbate the pitch up characteristic and require a more immediate reaction by the flight crew than was actually performed. Investigators believed that an immediate and abrupt forward control motion was counterintuitive to the crew and explained the delay in making full nose down control inputs. There was also a delay in application of nose down trim inputs which further inhibited recovery from the pitch up. Investigators stated that if the first officer had been more aggressive in applying both nose down elevator and trim, he might have been able to control the pitch up and avoid stalling the airplane. The safety board ultimately concluded that the mistrim of the airplane, based on incorrectly loaded cargo, "presented the flight crew with a situation that, without prior training or experience, required exceptional skills and reactions that cannot be expected of a typical line pilot."

Conclusion

The NTSB concluded that this accident was the result of multiple errors made during cargo loading, and calculation of the airplane center of gravity. Investigators determined that the airplane weight and center of gravity had been significantly miscalculated, and the resultant takeoff trim settings provided to the crew were incorrect. The NTSB further concluded that while the airplane retained sufficient control authority to effect a recovery from the rapid pitchup, the crew had not been trained to expect, or respond to, the encountered situation, especially in light of their having properly set the takeoff trim according to the dispatch paperwork. The NTSB did not fault the crew for their operation of the airplane.

Following the accident, Fine Air instituted a new training program for cargo loaders, covering "Aerodynamics, Physics and Theory of Flight," including aircraft weight, lift, stalls, center of lift, and CG. In another training area, "Weight and Balance for Ground Handlers," subjects included "proper use of company weight and balance data" and "effects of improper weight distribution on flight characteristics." A section on pallet building outlines the "proper use of the warehouse load sheet," cargo and weight distribution, legal ramifications if pallet weights are not correct, and the importance of correct weights on aircraft performance." Proper cargo loading procedures and installation of pallet locks were also included in the curriculum.

The NTSB issued 36 findings related to this accident. There were 5 findings regarding flight crew qualifications, airplane maintenance status, and the effect of weather. Two findings discussed the airplane flight path, and the crew's ability to recover from low altitude stalls. Five findings dealt with the airplane center of gravity position and the resulting flight characteristics. Twelve findings focused on airplane loading processes and related errors. Six findings focused on, and were critical of FAA oversight of Fine Air, and associated inspections. Three findings were specific to the flight data recorder, and the remainder of the findings discussed Fine Air's maintenance program.

The NTSB issued a probable cause statement as follows:

"The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the accident, which resulted from the airplane being misloaded to produce a more aft center of gravity and a correspondingly incorrect stabilizer trim setting that precipitated an extreme pitch-up at rotation, was (1) the failure of Fine Air to exercise operational control over the cargo loading process; and (2) the failure of Aeromar to load the airplane as specified by Fine Air. Contributing to the accident was the failure of the FAA to adequately monitor Fine Air's operational control responsibilities for cargo loading and the failure of the FAA to ensure that known cargo-related deficiencies were corrected at Fine Air."

The complete text of the findings can be viewed at the following link: (NTSB Findings)

The NTSB accident report is available at the following link: (Accident Report)

The NTSB issued 15 recommendations. One recommendation addressed pilot mistrim cues, and development of associated training, and the remaining majority of recommendations focused on various aspects of airplane weight and balance determination, and cargo loading and handling. Several recommendations addressed various aspects of flight data recorders that are not addressed in this accident module. The complete text of the recommendations is available at the following link: (NTSB Recommendations)

14 CFR 91.9 Civil aircraft flight manual, marking, and placard requirements.

14 CFR 121.135 Contents.

14 CFR 121.665 Load manifest.

Department of Defense Inspections of Fine Air

Prior to the accident, Fine Air was surveyed by the Department of Defense (DoD), following Fine Air's 1994 application to provide cargo services for the Air Mobility command. The initial survey concluded that Fine Air did not meet DoD requirements in six areas, including discrepancies in required flight documentation. The inspection rated Fine Air's management as "below average," its operations manual as "below average," and included comments that load manifests contained incorrectly totaled cargo weights. A second inspection conducted in 1996 determined that Fine Air met requirements to participate in the Air Mobility Command program, having ranked "average" in most inspected categories. However, the second inspection noted that there were still discrepancies in weight and balance load manifests.

FAA Inspections of Fine Air

In addition to routine FAA surveillance of Fine Air, two larger scale inspections of Fine Air were conducted in April 1995 and April 1997. The 1995 inspection, a Regional Aviation Inspection Program (RASIP) was conducted by an eight-member team, and included operations and airworthiness inspections, as well as ramp inspections of four Fine Air DC-8 airplanes. Among the findings from this inspection, wheels and tires were found unsecured in an airplane cargo area, and on another airplane a main cargo "Lock-Unlock" placard was found unreadable. In a June 1995 response to the inspectors, Fine Air stated that all the noted discrepancies were corrected prior to operation of the affected aircraft.

The April 1997 inspection was conducted as part of a National Aviation Safety Inspection Program (NASIP), and also encompassed operations and airworthiness. One of the areas of concern identified by the NASIP inspection was weight and balance. Among the weight and balance findings, it was determined that Fine Air had "no standards and schedules for the calibration of commercial scales used to determine cargo weights at Miami," and "loading schedules instructions...do not include instruction for calculation of weight and balance. The inspection also determined that Fine Air manuals did not "include procedures for weighing aircraft required by 14 CFR Part 121.135(b)(20)."

Fine Air Operations

One week prior to the accident the FAA Principal maintenance Inspector assigned to Fine Air was conducting an en route inspection. During an "outstation" stop in Santo Domingo, he discovered that the airplane was being improperly loaded. A scale intended for weighing individual pallets was in a location that prevented weighing of pallets and had to be moved. Further, three pallets were covered by nets that were unserviceable and had to be replaced. Also, on August 2, 1997, a Fine Air flight crew report stated that five "children," ages 15-17, and one adult unloaded and loaded an airplane during an outstation stop. The report added that "upon inspecting cargo before departure .... miscellaneous cargo was bulk loaded between pallets."

On the day of the accident, a loading scheme was developed for the scheduled airplane, but that airplane was delayed en route, so another airplane was scheduled in its place. The replacement airplane was slightly heavier, so the weight and balance calculations were redone, requiring a different pallet loading sequence and distribution. The new loading scheme was faxed to Aeromar, whose personnel were responsible to load the airplane, but there was no evidence that the new loading scheme was ever received by Aeromar, resulting in an erroneous attempt to load the airplane in the same manner as had been scheduled for the original airplane. After the accident, the investigators discovered several errors in each set of load calculations - use of a manifest for a similar, but incorrect airplane model, significantly incorrect weights for at least one pallet, and an incorrect trim setting for takeoff.

During the actual loading of the airplane, as a result of pallets being improperly loaded, with cargo extending beyond the edges of the pallets, it was discovered that many pallets did not fit properly, interfered with adjacent pallets, and prevented engagement of pallet locks. Three pallets were removed, and other pallets were moved from their planned positions to positions further aft than called for on the manifest. Further, the investigation determined that numerous pallet locks had been left unlocked, leaving the pallets in the unlocked positions essentially unrestrained.

The investigation was unable to determine the actual loading of the airplane, but numerous scenarios were investigated, most of which resulted in an aircraft center of gravity that was more aft than originally intended (perhaps beyond the aft limit), and a trim setting that was incorrect, calling for excessive nose up trim at takeoff.

The investigation concluded that while Fine Air calculated the weight and balance of the airplane, they did not supervise, or participate in the actual loading of the airplane. Aeromar loading personnel, including the loading supervisor, had relatively low experience, did not have expertise in airplane weight and balance, and did not understand the consequences of improperly loading an airplane, especially loading too far aft. They also did not understand the consequences of an incorrect takeoff trim setting in combination with an improper loading.

- Improper calculation of airplane weight and balance, leading to incorrect takeoff trim setting.

- Lack of qualified supervision during airplane loading process, leading to deviation from loading manifest, improper airplane loading, and uncertainty in the actual weight and balance.

- Improper pallet buildups, preventing proper loading and securing of pallets when loaded.

- Lack of understanding among airplane loaders of the consequences of errors in airplane loading.

- Incorrect takeoff trim setting, leading to uncontrollable airplane pitchup after liftoff.

- Deviations in loading were not made known to the flight crew.

- Airplane weight and balance calculations were correct

- The airplane was properly loaded

- Takeoff trim settings were correct

Previous Pitchup Event

During the investigation, it was learned that a previous pitchup event had occurred on one of Fine Air's DC-8s on July 13, 1997, less than a month before the accident. The captain of that flight stated that since it was a weekend, the cargo was loaded by a freight forwarder, contracted when Fine Air freight loaders were off duty. He stated that during takeoff, as the airplane reached V1, the nosewheel lifted off the ground. At VR, the airplane rotated and lifted off without any control inputs by the pilot flying. Forward control pressure and nose down trim were required to maintain the intended initial climb speed of V2 + 10 knots.

The takeoff trim setting was 3.4 units (airplane nose up), but after retrimming to maintain control, the resulting trim setting was minus 1.5 units (airplane nose down). Following the trim adjustments, the captain stated he had no difficulty controlling the airplane, so elected to continue to his destination. He stated that the first officer later called the company via radio and complained about the loading. The captain did not file an irregularity report, but did discuss the event with his director of operations, who in turn discussed the event with the assigned FAA Principal Operations Inspector. No further action was taken following the incident.

Previous Accidents

There were a number of accidents prior to the Fine Air accident that resulted from similar circumstances. Some of these included:

On December 15, 1973, a Lockheed Super Constellation, operated by aircraft Pool Leasing, and carrying Christmas trees, crashed after taking off from Miami. Factors in this accident were determined to be, "improper cargo loading, a rearward movement of unsecured cargo resulting in a center of gravity shift aft of the allowable limit, and deficient crew coordination."

The accident report stated that cargo was not secured properly and that the "loading supervisor did not receive any guidance with regard to load distribution. He stated that the original intent was to load all of the trees on hand into the aircraft. When it was apparent that this could not be done, he was told to put as many on as possible."

On January 11, 1983, a United Airlines cargo DC-8 crashed just after takeoff in Detroit. Witnesses stated that the takeoff roll, and rotation were normal, but after liftoff the airplane pitch "steepened abnormally." At about 1000 feet, the airplane rolled to the right and descended rapidly to the ground. The airplane was destroyed by impact and post-crash fire, and the three crew members on board were killed.

The accident investigation determined that the stabilizer trim was set at 7.5 units, which had been the landing trim setting. The Safety Board concluded that the probable cause of the accident "was the flight crew's failure to follow procedural checklist requirements and to detect and correct a mistrimmed stabilizer before the airplane became uncontrollable." The accident report noted that simulations "conducted after the accident demonstrated that immediately after liftoff when nose-down elevator forces were applied, the rate of rotation slowed, giving the impression that it would be possible to arrest the rotation solely with forward control input. Recovery of the airplane at rotation was possible if immediate nose-down trim was applied along with full forward elevator input. However, once the airplane left the ground and started to accelerate, recovery was improbable."

On March 12, 1991, a DC-8-62 operated by Air Transport International departed the right side of the runway during a rejected takeoff. The airplane was destroyed by fire, but the three crewmembers and two jumpseat passengers escaped with only minor injuries. The captain rejected the takeoff after determining that "the nose was extremely heavy" at rotation and that the "force on the control column was such that I could not let go with one hand until the nose was on the ground." The probable causes of the accident were determined to be "improper preflight planning and preparation, in that the flight engineer miscalculated the aircraft's gross weight by 100,000 pounds and provided the captain with improper takeoff speeds; and improper supervision by the captain. Factors relating to the accident were an improper trim setting provided to the captain by the flight engineer, inadequate monitoring of the performance data by the first officer, and the company management's inadequate surveillance of the operation."

Post-accident Inspections

Following the accident, between August 20 and 27, 1997, an FAA Regional Aviation Safety Inspection Program (RASIP) Team conducted an inspection of Fine Air's operations. Relative to the circumstances of the accident, the RASIP team found "problems in the area of weight and balance control, to include ground handling, weighing of cargo, security of cargo on pallets, accuracy of individual pallet weights, and condition of pallets and nets used to restrain cargo has an impact on safety of flight."

The RASIP team observed the loading and unloading of several airplanes, one observation stated that, upon arrival in Miami, "When the door was opened #2 pallet was found not secured by the side locks. There are 4 locks at the cargo door entry. The pallet was sitting on locks 1, 2 and 4 and #3 was not engaged. The cargo on this pallet had shifted jamming the pallet which was not properly secured. The net and approximately ½ the cargo was removed to remove the pallet. The following was observed

concerning the security of the cargo:

- #3 pallet net frayed, broken and held together with yellow ‘ski rope.'

- #5 pallet net broken in several areas with rope securing the corners.

- #6 pallet broken at 2 corners and net secured with yellow rope.

- #7 pallet net frayed and broken.

- #8 pallet net frayed and broken with the net secured at only 2 places on end of the pallet.

- #9 pallet had 3 of 4 points of the net attached to the pallet.

Observation of the forward lower cargo compartment revealed the flyaway kit not secured. A main wheel and tire assembly had shifted aft in the compartment and a brake assembly had fallen out of its box and shifted aft in the compartment. Combined weight was approximately 750# [pounds]."

On another flight pallet weights were found to be discrepant by as much as 1000 pounds when compared to weights listed on the load sheet. The actual pallet weights were lower than the manifested total weight, but the weight distribution was incorrect, due to the errors, and the resultant takeoff trim setting had been, therefore, incorrect.

On multiple other flights, cargo nets were improperly secured to the pallets, nets were in poor condition, some using yellow nylon rope which is not authorized for use on aircraft. Cargo pallets were loaded with no weights attached, and on at least one occasion, errors in CG calculations caused the cancellation of a flight. In aggregate, the investigators concluded that there was "no apparent operational control" of loading operations exercised by Fine Air.

As a result of the numerous safety concerns identified by the RASIP inspection, on September 12, 1997, approximately one month after the accident. Fine Air signed a consent agreement with the FAA, agreeing to cease all 14 CFR Part 121 operations until it demonstrated to the FAA that it was in compliance with all applicable regulations and conditions listed in the consent agreement. Fine Air also agreed to pay the FAA $1.5 million for costs to "investigate, review, and re-inspect Fine Air and establish and ultimately enforce" the consent agreement. Fine Air agreed to review and revise the following:

"Cargo handling system and procedures that will ensure accuracy of cargo weights, restraint and loading for all flights under the operational control of ine Air. This system will include but not be limited to, maintenance program or cargo pallets and cargo restraint devices, cargo pallet loading procedures, cargo weighing procedures, system for control of scales and maintaining calibration records for scales used for weighing cargo, aircraft loading procedures, aircraft weight and balance procedures.

A training program for cargo handlers and other personnel responsible for cargo handling and aircraft loading.

Crewmember and flight follower training to include cargo handling, aircraft loading procedures, and aircraft weight and balance and performance computations.

A system to ensure all 'wet leases' and interchange agreements are properly authorized in operations specifications prior to conducting any operations under the agreement.

A maintenance and inspection program for aircraft cargo floors. The maintenance program for flight data recorders."

On October 28, 1997, the FAA allowed Fine Air to resume operations, stating that Fine Air had improved its processes and procedures, and had met the conditions of the consent agreement. The FAA further announced that it would continue to evaluate its overall inspection program for cargo carriers.

Changes in Fine Air Cargo Loader Training

Based on the terms of the consent agreement, Fine Air developed a new training program for cargo loaders and supervisors. The training was comprised of 7 hours of classroom training covering basic aerodynamics, weight and balance, safe handling of cargo and pallet building, and loading and unloading. Dangerous goods training (16 hours) was also developed for shippers, packers, and cargo agents. An 8-hour version of the same training was provided to loading and warehouse personnel. Additionally, a "Loading Supervisor Certification" form was developed that required loading supervisors to certify that the airplane "was loaded in accordance with Fine Airlines loading requirements, and that all locks, in all pallets positions are properly installed, and in the pallet locked position."

The new training program, incorporated into Fine Air's training manual, addressed a range of loading issues. A section on the "Aerodynamics, Physics and Theory of Flight" covered a variety of subjects, including aircraft weight, lift, stalls, center of lift, and CG. In "Weight and Balance for Ground Handlers," subjects included "proper use of company weight and balance data" and "effects of improper weight distribution on flight characteristics." A section on pallet building outlines the "proper use of the warehouse load sheet," cargo and weight distribution, "legal ramifications if pallet weights are not correct, importance of correct weights on aircraft performance, and pallet weight certification." Proper cargo loading procedures and installation of pallet locks were also included in the curriculum.

Changes in FAA Inspector Guidance

Both the pre- and post-accident RASIP and NASIP inspections of Fine Air determined that FAA oversight and surveillance were inadequate and should have detected the numerous discrepancies found during the focused inspections. As a result, on September 5, 1997, the FAA issued two bulletins relating to cargo operations and FAA surveillance of cargo loading operations. Flight Standards Information Bulletin for Airworthiness (FSAW) 97-21, titled, "Acceptable Means of Maintaining Cargo Containers, Pallets, and Netting Installed on Transport Category Aircraft" outlined the FAA's policy regarding the "acceptable means of dealing with cargo containers, pallets, and netting installed in transport category aircraft."

FSAW 97-21 stated that during routine surveillance FAA inspectors had "increasingly observed what may be unserviceable cargo containers, pallets, netting and other restraint devices loaded into air carrier aircraft." The bulletin added the following:

In many cases, the restraint systems identified above and cargo loading personnel are provided by a freight forwarding company under a lease agreement. This has caused some confusion and concerns about who is responsible for the restraint systems and the training of the cargo loaders. Further, questions have arisen regarding the services provided by the freight forwarding company being considered contract maintenance.

According to FSAW 97-21, the airworthiness of an aircraft, as defined by CFR Part 121, "includes cargo containers, pallets, and any other restraint system installed on the aircraft." The bulletin stated that air carriers are "ultimately responsible for training their personnel to the requirements of their manual" and that "ground support equipment and cargo loading personnel should not be considered contract maintenance." FSAW 97-21 concluded that "principal inspectors should ensure that adequate procedures are in place in the operator's manual to ensure cargo restraint equipment conform to proper standards and are in condition to perform their intended function."

Further, Joint Flight Standards handbook Bulletin for Airworthiness and Air Transportation (HBAT) 97-12, "Special Emphasis Surveillance of Part 121 Air Carrier Cargo Loading Procedures" provided a reemphasis and expansion of related FAA policy and guidance regarding weight and balance control procedures, cargo loading procedures, and loading schedules and instructions.

The bulletin placed a special emphasis on ramp checks of all part 121 operators that load any type of cargo, including passenger baggage. One important addition was to require that if a certificate holder (airline), utilizes individuals who are not the certificate holder's employees, those individuals must be directly supervised by an appropriately qualified supervisor employed by the certificate holder.

Both the FSAW and HBAT are available at the following links: (FSAW 97-21, HBAT 97-12)

Cargo Strategic Action Plan

In April 2000, the FAA Flight Standards Service formed a Cargo Strategic Planning Group, to develop an action plan by collecting and analyzing data and evaluating cargo operations and associated regulatory requirements. The group was also chartered to "assign roles, responsibilities, and organizational tasks to establish accountability for addressing future cargo issues. The group was to report back to the directors of the Flight Standards Service, and the Aircraft Certification Service."

In March 2001, the group released the Cargo Strategic Action Plan. The plan articulated a complete FAA response to address issues related to transporting cargo, and to respond to NTSB recommendations A-98-45 through A-98-48. The scope of the plan included issues ranging from certification issues, cargo operations, airworthiness, FAA oversight of cargo operators, and operator training, to airplane parts modification. Rulemaking was recommended as the comprehensive solution to identified issues, and further recommended interim measures while rulemaking activity was underway.

As interim measures, the group proposed consistent application of FAA advisory circulars AC 120-27C, Weight and balance, AC 25-18, Aircraft Modified for Cargo, 14 CFR 25.1881(c), Weight and Loading, and 14 CFR 119.49(a)(9), Authorization for the method of Weight and Balance. Longer term solutions were to include the establishment of FAA internal responsibility for air cargo loading operational approvals and surveillance, and rulemaking to create a Cargo Management System. Associated training, guidance and advisory material needed to be developed as well as qualification and training standards for air cargo loading personnel.

Airplane Life Cycle:

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories:

- In-flight Upsets

Groupings:

- Loss of Control

Accident Common Themes:

- Organizational Lapses

- Human Error

Organizational Lapses

Fine Air and Aeromar had entered into a “wet-lease” agreement providing that Aeromar would lease Fine Air’s airplanes in order to ship cargo. Both parties had duties per the wet-lease arrangement. Airplane weight and balance calculations were performed by Fine Air personnel, and faxed to Aeromar, whose personnel were responsible to load the airplane. The scheduled airplane, N30UA, became unavailable for the flight, and N27UA was substituted at the last minute. The weight and balance calculations for N30UA were modified to accommodate the weight differences between the two airplanes, but it could not be established by the investigation that the modified instructions were received by Aeromar. Aeromar attempted to load the airplane per the original instructions (for N30UA), but interference between pallets which prevented proper securing of many pallets led to a modified loading, which had not been planned, and differed significantly from the intended loading for the accident airplane. Investigators could not establish that the loading deviations were communicated to Fine Air in order to recalculate the airplane weight and balance. Investigators further determined that the unplanned deviation from the intended loading configuration led to an extremely aft CG, which in combination with an incorrect (too aft) takeoff trim setting, led to an uncontrollable airplane pitchup after liftoff, and the crash. During the loading process, none of the deviations were made known to Fine Air, whose personnel were responsible for calculating airplane weight and balance, and who might have stopped the loading process until the errors could be corrected. Further, Aeromar personnel had not been trained regarding airplane weight and balance, and therefore did not understand the significance of the loading deviations, and the consequences they would impose on the accident airplane.

The following 109 accidents/hull losses are attributed to cargo. No attempt has been made to record all such occurrences.

| date | type | registration | operator | fat. | location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Mar-50 | Avro 689 Tudor 5 | G-AKBY | Fairflight | 80 | near Llandow |

| 23-Aug-62 | Douglas R4D-1 (DC-3) | HK-794 | Líneas Aéreas Taxader | 12 | Barrancaberm... |

| 15-Sep-64 | Douglas C-47A-80-DL (DC-3) | HK-319 | Avianca | 2 | near Condoto |

| 12-Sep-66 | Douglas DC-7CF | N2282 | Airlift Int. | 0 | Tokyo-Tachik... |

| 28-Feb-67 | Fokker F-27 Friendship 100 | PI-C501 | Philippine Air Lines | 12 | near Mactan Islan... |

| 16-Oct-70 | Lisunov Li-2 | CCCP-84771 | Aeroflot / Northern | 0 | Leshukonskoy... |

| 15-Dec-73 | Lockheed L-1049H Super Constellatio | N6917C | Aircraft Pool Leasing Corp. | 3+ 6 | near Miami Intern... |

| 23-Feb-74 | Curtiss C-46A-45-CU | CP-1052 | SAVCO | 7 | San Francisc... |

| 21-Aug-76 | Convair CV-880-22M-3 | N48060 | Airtrust Singapore | 0 | Singapore-Se... |

| 16-Dec-76 | Convair CV-880-22M-22 | N5865 | Air Trine Inc | 0 | Miami Intern... |

| 13-Dec-77 | Douglas C-53 (DC-3) | N51071 | National Jet Services | 29 | Evansville-D... |

| 25-May-78 | Convair CV-880-22-2 | N8815E | Groth Air | 0 | Miami Intern... |

| 9-Jul-81 | Howard 500 | C-GKFN | Kelowna Flightcraft | 3 | Toronto Inte... |

| 16-May-82 | DHC-6 Twin Otter 200 | N103AQ | Kodiak Aviation, opf. Wien Air Alaska | 0 | Hooper Bay, AK |

| 22-Jun-83 | Douglas C-47A-10-DK Dakota 3 | C-GUBT | Skycraft Air Transport | 2 | Toronto Inte... |

| 28-Aug-86 | Howard 250 | N252K | Southwest Airlift | 2 | Texarkana Mu... |

| 23-Nov-87 | Beechcraft 1900C | N401RA | Ryan Air Service | 18 | Homer Airpor... |

| 23-May-88 | Boeing 727-22 | TI-LRC | LACSA | 0 | San José-Jua... |

| 24-Sep-88 | Tupolev 154B-2 | CCCP-85479 | Aeroflot / Armenia | 0 | Aleppo Airpo... |

| 13-Jan-89 | Tupolev 154S | CCCP-85067 | Aeroflot / International | 0 | Monrovia-Rob... |

| 8-May-89 | Beechcraft 99 | SE-IZO | Holmström Flyg | 16 | near Oskarshamn A... |

| 22-Dec-91 | Douglas DC-3A | D-CCCC | Classic Wings | 28 | Heidelberg-H... |

| 13-Jul-92 | Shorts SC.7 Skyvan 3A-200 | N20086 | Arctic Circle Air Service | 1 | Bethel, AK |

| 20-Jul-92 | Tupolev 154B | 85222 | Tbilisi Aviation Enterprise | 24+ 4 | Tbilisi-Novo... |

| 13-Oct-92 | Tupolev 154B-2 | CCCP-85528 | Aeroflot / Belarus | 0 | Vladivostok ... |

| 26-Aug-93 | Let L-410UVP-E | RA-67656 | Sakha Avia | 24 | near Aldan Airpor... |

| 17-Aug-95 | BN-2A Islander | 4X-CCO | Barak Aviation Services | 0 | Haifa Airpor... |

| 7-Aug-97 | DC-8-61F | N27UA | Fine Air | 4+ 1 | Miami Intern... |

| 13-Aug-97 | Beechcraft 1900C | N3172A | Ameriflight | 0 | Seattle/Taco... |

| 17-Dec-97 | Ilyushin 18V | RA-75554 | Ramaer Cargo | 0 | Johannesburg... |

| 3-Dec-98 | British Aerospace BAe-748-335 Srs. | C-FBNW | Bradley Air Services | 0 | Iqaluit Airp... |

| 12-Jan-99 | Fokker F-27 Friendship 600 | G-CHNL | Channel Express | 2 | Guernsey Air... |

| 15-Jan-00 | Let L-410UVP-E | YS-09-C | TACSA | 5 | San José |

| 17-Mar-00 | Douglas C-47A-5-DK Dakota 3 (DC-3C) | C-FNTF | Points North Air Services | 2 | Ennadai Lake... |

| 3-Mar-01 | Shorts C-23B+ Sherpa (330) | 93-1336 | Florida ANG | 21 | near Unadilla, GA |

| 18-Sep-01 | Let L-410UVP-E | TG-CFE | Atlantic Airlines | 8 | Guatemala Ci... |

| 13-Apr-02 | GAF Nomad N.24A | OY-JRW | Nomad Fleet | 0 | Weston-on-th... |

| 17-Jun-03 | MD-88 | TC-ONP | Onur Air | 0 | Groningen-Ee... |

| 25-Dec-03 | Boeing 727-223 | 3X-GDO | UTA | 141 | Cotonou Airp... |

| 18-May-04 | Antonov 2P | UN-70276 | Araiavia | 1 | Bozoy |

| 2-Feb-05 | Canadair CL-600-1A11 Challenger 600 | N370V | DDH Aviation, opf. Platinum Jet Management | 0 | Teterboro Ai... |

| date | type | registration | operator | fat. | location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13-Feb-56 | Bristol 170 Freighter 31 | CF-FZU | Maritime Central Airways | 3 | Frobisher Ba... |

| 24-Nov-58 | Antonov 2 | CCCP-L5676 | Aeroflot / Magadan | 0 | Anadyr |

| 15-Dec-61 | Curtiss C-46 | AN-AOE | LANICA | 2 | Managua-Las ... |

| 6-Jan-67 | Curtiss C-46F-1-CU | N30046 | Channel Air Lift | 3 | Hilo Interna... |

| 2-Jul-70 | Shorts SC.7 Skyvan 3-200 | N21CK | Jetco | 2 | Potomac Rive... |

| 20-Nov-77 | Bristol 170 Freighter 31M | C-FWAD | Norcanair | 1 | Hay River Ai... |

| 25-May-79 | DHC-4A Caribou | N581PA | Sea Airmotive | 3 | Bullen Point... |

| 7-Feb-81 | Tupolev 104A | CCCP-42332 | Soviet Navy | 51 | near Leningrad |

| 22-Jun-83 | Douglas C-47A-10-DK Dakota 3 | C-GUBT | Skycraft Air Transport | 2 | Toronto Inte... |

| 13-Jan-89 | Tupolev 154S | CCCP-85067 | Aeroflot / International | 0 | Monrovia-Rob... |

| 18-Jan-89 | Douglas C-47A-70-DL (DC-3C) | XB-DYP | American Air Freight | 0 | Laredo Inter... |

| 26-Apr-89 | SE-210 Caravelle 11R | HK-3325X | Aerosucre Colombia | 5+ 2 | Barranquilla |

| 13-Jul-92 | Shorts SC.7 Skyvan 3A-200 | N20086 | Arctic Circle Air Service | 1 | Bethel, AK |

| 16-Jun-93 | DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 | PK-NUL | Merpati Nusantara | 1 | Nabire Airpo... |

| 28-Jan-95 | 747-238B | N706CK | American International Airways, Inc | 0 | Ypsilanti, MI |

| 2-Feb-08 | Boeing 747-200 | N527MC | Atlas Air | 0 | Lome, Togo |

| 29-Apr-13 | Boeing 747-400BCF | N949CA | National Air Cargo | 7 | Bagram, Afghanistan |

| 25-Nov-13 | DC-6 | N100C | Everts Air Cargo | 0 | Nuiqsut, AK |

| 16-Oct-14 | 737-330 | N301KH | Aloha Air Cargo | 0 | Honolulu, HI |

| date | type | registration | operator | fat. | location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-Jun-49 | Curtiss C-46D-5-CU | NC92857 | Strato-Freight | 53 | near San Juan-Isl... |

| 22-Mar-58 | Lockheed 18-56 Lodestar | N300E | Ayer Lease Plan, opf. private | 4 | near Grants, NM |

| 29-Oct-60 | Curtiss C-46F-1-CU | N1244N | Arctic Pacific | 22 | Toledo-Expre... |

| 20-Oct-65 | Douglas C-47A-25-DK (DC-3) | PI-C144 | Philippine Air Lines | 1 | Manila |

| 18-Feb-69 | Douglas DC-3 | VT-CJH | Indian Airlines | 0 | Jaipur-Sanga... |

| 17-Oct-71 | Douglas C-47A-75-DL (DC-3) | HK-595 | Aerolíneas TAO | 19 | San Vicente ... |

| 16-Mar-76 | Beechcraft 99A | N7997R | Command Airways | 0 | Poughkeepsie... |

| 17-Jul-76 | Tupolev 104A | CCCP-42335 | Aeroflot / East Siberia | 0 | Chita Airpor... |

| 24-Jul-79 | de Havilland DH-114 Heron 2D | N575PR | Prinair | 8 | Saint Croix-... |

| 24-May-80 | Convair CV-240-0 | N300GR | private | 3 | near Daytona Beac... |

| 2-Sep-81 | Embraer 110P1 Bandeirante | HK-2651 | El Venado | 21 | near Paipa |

| 23-Dec-82 | Antonov 26 | CCCP-26627 | Aeroflot / Turkmenistan | 16 | near Rostov Airpo... |

| 25-Aug-83 | Yakovlev 40K | CCCP-87201 | MAP Arsenyev | 0 | Omsukchan Ai... |

| 2-Aug-84 | BN-2A Islander | N589SA | Vieques Air Link | 9 | near Vieques |

| 16-Sep-84 | Antonov 2T | SP-AMK | APRL | 11 | Opole |

| 21-May-85 | Antonov 2 | CCCP-04326 | Aeroflot / Tyumen | 0 | Tadibeyakha |

| 20-Jun-85 | Antonov 2TP | CCCP-91783 | Aeroflot / Yakutsk | 0 | Moma |

| 4-Jul-85 | Antonov 2R | CCCP-55710 | Aeroflot / Krasnoyarsk | 0 | Baykit (BKT) |

| 31-Mar-87 | Antonov 2P | SP-DNM | ZUA | 2 | near Pilisszentlélek |

| 2-Jan-90 | CASA/Nurtanio NC-212 Aviocar 200 | PK-PCM | Pelita Air Service | 9 | Banten Bay, ... |

| 29-Jan-90 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | N4688B | Airborne Express | 2 | near Burlington I... |

| 6-Apr-90 | Learjet 25C | PT-CMY | Transamérica Táxi Aéreo | 2 | Juiz De Fora... |

| 16-Sep-91 | Antonov 74 | CCCP-74002 | Aeroflot | 13 | near Lensk Airport |

| 28-Aug-93 | Yakovlev 40 | 87995 | Tajikistan Airlines | 82 | near Khorog |

| 26-Dec-93 | Antonov 26B | CCCP-26141 | Kuban Airlines | 35 | Gyumri-Lenin... |

| 29-Sep-94 | Rockwell 1121B Jet Commander | LV-WEN | Radeair | 8 | near Córdoba-Paja... |

| 29-Oct-94 | Antonov 2R | RA-33008 | Yakutavia | 7 | Batagay |

| 18-Dec-95 | Lockheed L-188C Electra | 9Q-CRR | Trans Service Airlift | 141 | near Cahungula, L... |

| 30-Nov-96 | DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 | HK-2602 | ACES | 14 | near Medellín |

| 25-Jun-97 | Boeing 727-21F | HK-1717 | Aerosucre Colombia | 0 | Bogotá-Eldor... |

| 13-Jul-98 | Ilyushin 76MD | UR-76424 | ATI Aircompany | 8 | near Ra'sal-Khaym... |

| 29-Jul-98 | Embraer 110P1 Bandeirante | PT-LGN | Selva Taxi Aéreo | 12 | near Manaus, AM |

| 24-Aug-98 | Antonov 32B | HK-4007X | SADELCA Colombia | 0 | Leticia-Alfr... |

| 28-Aug-98 | Dassault Falcon 20 | N126R | Reliant Airlines | 0 | El Paso Inte... |

| 28-Dec-99 | Cessna 208A Caravan 675 | C-FGGG | Seair | 0 | near Abbotsford A... |

| 28-Apr-01 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | LV-WSC | Les Grands Jorasses | 10 | near Roque Pérez, BA |

| 14-Jul-01 | Ilyushin 76TD | RA-76588 | Russ Air | 10 | near Chkalovsky A... |

| 12-Jun-02 | Lockheed MC-130H Hercules | 84-0475 | USAF | 3 | near Gardez |

| 17-Jan-04 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | C-FAGA | Georgian Express | 10 | near Pelee Island... |

| 4-Dec-04 | Convair CV-340-70 | N41626 | Miami Air Lease | 0 | North Miami ... |

| 15-Mar-05 | Antonov 26B-100 | OB-1778-P | ATSA | 0 | Lima-J Chave... |

| 17-Jul-05 | Cessna 525 CitationJet | N13FH | Hertrich Aviation | 0 | Old Bridge A... |

| 5-Jul-07 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | N208EC | Lancton Taverns Ltd. | 2 | near Connemara Ai... |

| 19-Dec-08 | BN-2A-20 Islander | YJ-RV2 | Air Vanuatu | 2 | near Olpoi-Lajmol... |

| 15-Nov-09 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | ZS-OTU | Aviation at Work, opf. Air Nave | 3 | near Windhoek-Ero... |

| 9-Sep-11 | Cessna 208B Grand Caravan | PK-VVE | Susi Air | 2 | near Notnare Vill... |

Technical Related Lessons

Particularly for cargo operations, verification/validation of airplane weight and balance, and corresponding takeoff trim settings, is crucial to operational safety. (Threat Category: Inflight Upsets)

- In this accident, weight and balance calculations were initially incorrect, due to the last-minute switch in airplanes, and airplane cargo loading deviated from instructions, further compounding the error. Investigators determined that the modifications to the loading plan, made by the loaders, during actual airplane loading, and without regard to written loading instructions, resulted in a very aft airplane CG, perhaps beyond the allowable aft limit. The corresponding takeoff trim setting was also incorrect and was based on an airplane CG that was expected to be further forward than the CG that resulted after the loading errors. The combination of a CG that was further aft than intended, and excessive nose-up trim resulted in an uncontrollable airplane pitchup after liftoff, airplane stall, and the accident.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Robust supervision of airplane cargo loading, such that loading instructions are properly followed, without deviation, is critical to operational safety. If loading deviations become necessary, effects on airplane weight and balance, and takeoff trim settings should be determined and verified before takeoff. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapses)

- Investigators determined that during the loading of the accident airplane, problems with interference between adjacent pallets required modification of the written load plan. The resultant loading deviations allowed adjacent cargo pallets to fit together more snugly but did not account for the effects on airplane weight and balance. Though unable to be conclusively determined by the investigation, it was believed that the resultant CG, combined with an incorrect takeoff trim setting led to an uncontrollable situation after liftoff, and caused the accident.

Cargo loading, even to the level of individual pallet loads, should be conducted in a manner that accommodates, and doesn't compromise the ability to properly secure the cargo and/or pallets. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapses)

- In loading the accident airplane, many of the individual pallets were stacked such that some portion of the palletized "big-paks" extended beyond the edges of the pallets. This resulted in a number of pallets that could not be properly secured by extending the floor locks to maintain individual pallets in position. As a result, cargo loaders moved pallets, counter to printed loading instructions, and rotated at least one pallet in order to allow pallet locks to be extended. It was never determined by the investigation if all the required pallet locks were extended before the airplane departed, but at the accident scene, investigators determined that the majority of available locks on the airplane were not extended, and had not failed, indicating that many pallets had not been properly secured.