Boeing 737-300 and Fairchild Metroliner SA-227-AC

USAir Flight 1493, N388US

Photo copyright Frank C. Duarte Jr. - used with permission

Skywest Metroliner at LAX (bottom)

Photo copyright Frank Schaefer - used with permission

Skywest Flight 5569, N683AV

Los Angeles, California

February 1, 1991

Skywest Flight 5569, a Fairchild Metroliner SA-227-AC, was positioned on runway 24 left at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), and awaiting clearance for take-off from air traffic control. As the aircraft waited, USAir Flight 1493, a Boeing 737-300, inbound from Columbus, Ohio, was cleared for a visual approach on runway 24 left. Just after touchdown, the 737 collided with the Metroliner that was still waiting in position. The collision occurred simultaneously with the aircraft's nose wheel contacting the runway.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found that the probable cause of the accident was the failure of the Los Angeles Air Traffic Facility Management to:

- implement procedures that provided redundancy measures for position awareness, and

- provide adequate direction and oversight of air traffic control facility managers.

The investigation also believed the FAA failed to provide effective quality assurance of the Air Traffic Control (ATC) system. All 12 passengers and crewmembers aboard the Skywest flight were killed. Twenty-two of the 89 passengers and crew on the USAir flight were killed.

Photo copyright Sam Chui - used with permission

The USAir Boeing 737, registration N388US, flight number USA1493, took off from Columbus, Ohio, at 1307 hours (local time) on February 1, 1991, en route to Los Angeles, California.

The Skywest Fairchild Metroliner, registration N683AV, flight number SKW5569, was preparing to leave Los Angles International Airport (LAX) to fly to Palmdale, California, at around 1800 hours (local time).

Both aircraft had flown other legs throughout the day, and had crew changes prior to these specific flights. No remarkable maintenance issues were noted for either aircraft. Official sunset for the Los Angeles area occurred at 1723, and the sky was dark on the horizon.

Air Traffic Control

The Los Angeles air traffic control (ATC) tower was classified as a level V, or the highest level rating in 1991. The entire runway 24 complex is north and west of the tower. The workload and complexity for the air traffic controllers at the time of the accident was noted as "light to moderate." A normal staffing load for evenings at the LAX tower included 13 personnel: 11 ATC specialists, 1 traffic management coordinator, and 1 area supervisor. As events unfolded, four controllers in the tower communicated in some manner with the two accident aircraft.

Controllers at different facilities have varying responsibilities. Airports are controlled by ground and local controllers. Communications between these two roles is a highly disciplined process. Ground control (GC) is vital because they are responsible for directing traffic to and from the runways. They impact the sequencing of departure aircraft, movement on the taxiways, and an airport's operating efficiency. The local control position (LC) also commonly referred to as "tower" is typically located near the ground control position, so that both controllers may more easily coordinate or communicate with each other. Local controllers are responsible for aircraft within 3 miles of the airport, runway operations, and all departures and landings on the runways. In coordinating traffic, GC must request approval from LC when an aircraft or vehicle needs to cross any active runway, and LC must provide information to GC that may affect the taxiways.

To effectively communicate between controller positions, flight progress strips provide one method to track aircraft. These strips are 1x6" strips of paper housed in a plastic "boat" that include the aircraft's call sign, model type, departure airport, route, and destination. The strips are placed in a "podium", stacked top to bottom in order of their handoff. Though there are occasional lapses in placing a strip on the podium, it is normally easy for controllers to recover when a gap is noticed. The national operating procedures in 1991 required ground control positions to use flight progress strips. A facility supplement had been issued at LAX on January 11, 1990, that was contrary to the national operating procedures stating "there is no strip marking required of ground control."

In addition to using flight progress strips to track aircraft, busier airports have redundant radar devices to help with awareness of aircraft positions such as airport surface detection equipment (ASDE) or the bright radar indicator tower equipment (BRITE) system. At the time of the accident, the ASDE equipment at the Los Angeles airport had a long history of unreliability and was not in use.

Cockpit Voice Recorder Transcript

Around 1758 hours on February 1, 1991, when this transcript begins, the Skywest Metroliner begins taxiing from terminal 6, gate 32, to runway 24 left. The USAir 737 is cleared to follow a standard descent procedure. This transcript comes from cockpit voice recorders and air traffic recordings. (Note: In the following transcripts, two traffic controllers are identified. The TRACON controller is noted as AR1, and the local controller is noted as LC2). Further, only pertinent sections have been included. Other sections not considered relevant to the events of the accident are omitted here, but may be found in the actual CVR transcript included in the accident report.

1757:27: AR1 to USA1493 ...intercept the runway two four right localizer, maintain one zero thousand.

1759:00: AR1 to USA1493 Do you have the airport in sight?

1759:04: USA1493 Affirmative.

1759:06: AR1 to USA1493 (Cleared visual approach) two four left...at or above eight thousand.

1759:11: USA1493 Cleared to visual for two four left USA1493.

1759:57: USA1493 Ah, just confirm the visual for USA1493 is to two four left.

1800:02: AR1 That's correct USA1493

1800:04: USA1493 Thank-you.

1803:05: AR1 USA1493...Contact Los Angeles tower one three three point niner at ROMEN. Good night.

1803:10: USA1493 Thirty three nine. Good night.

1803:37: SKW5569 to LC2 SKW5569 at forty five, we'd like to go from here if we can.

1803:41: LC2 to SKW5569 SKW5569 taxi up to and hold short two four left.

1803:44: SKW5569 Roger. Hold short.

Another Metroliner aircraft, WW5006, was midfield at taxiway 52, waiting to cross runway 24 left. The crew of WW5006 had inadvertently departed the radio frequency that communicated with LC2, so the controller was unable to give them clearance to cross the runway.

1804:35: USA1493 USA1493 inside of ROMEN.

1804:44: LC2 SKW569 taxi in position and hold runway two four left. Traffic crossing down field.

1804:49: SKW5569 OK. Two four left position and hold.

When the Wings West WW5006 crew recognized the mistake, they returned to the correct frequency and contacted LC2. Repeated attempts to communicate with the flight crew generated additional workload, where extraneous conversation created a distraction. The WW5006 Metroliner was then cleared to cross runway 24 left at 1805:16 by LC2.

1805:29: LC2 to USA1493 USA1493 for the left side of two four left

1805:51: LC2 to USA1493 USA1493 cleared to land runway two four left.

1805:55: USA1493 Cleared to land two four left 1493.

A third Metroliner, WW5072, called LC2 at 1806:08 stating that they were ready for takeoff. When LC2 checked for the aircraft's flight progress strip, there wasn't one in the proper slot so the controller asked the supervisor where it might be located. In searching, it was found misfiled in the clearance delivery (CD) position, meaning the departure clearance hadn't been given. At 1806:30 LC2 verified with the Wings West WW5072 flight crew that the departure clearance had, in fact, been issued.

At 1806:59, the sound of the collision is recorded. The accident report notes that the first officer considered the approach stabilized, and derotated slowly per company procedures. As the nose of the airplane lowered onto the runway, he observed an airplane on the runway through his windscreen immediately in front and below. The landing lights of the 737 were reflected off the propellers of the airplane in front.

The collision occurred simultaneously with the airplane's nose wheel contacting the runway, followed by an explosion and fire. The two aircraft slid to the left side of the runway, into an unoccupied fire station. All 10 passengers and 2 crewmembers on Skywest 5569 were fatally injured. 67 passengers and crew members were evacuated from the USAir 737, and 22 were fatally injured.

Evacuation

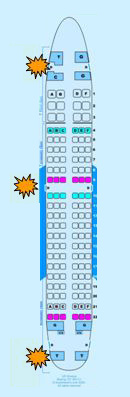

Four of the six exits on USA 1493 were used for the emergency evacuation. The forward, left-hand door (L-1) was damaged when the aircraft impacted the abandoned fire station. The aft, left-hand door was opened by a flight attendant, but closed and not used because of the flames along the left side of the airplane. Because of the fire, only two passengers were able to escape from the left overwing emergency exit.

identifying areas of fire outside emergency exits

Photo copyright Dan Brownlee - used with permission

The forward, right-hand exit door was opened, but the slide did not deploy as it had been damaged during the collision. There was a 5 foot drop to the ground from the door sill. Two passengers exited at this location.

About 37 passengers escaped through the right overwing emergency exit. Their egress was hampered by the passenger seated next to the exit, who was very frightened and unable to open the exit. A different passenger crawled over the seat back and opened the overwing exit, pushed the frightened passenger out the window, and then followed. As the remaining passengers began exiting the window exit, two passengers had an altercation in front of the exit, blocking the escape path for several seconds.

Because of the delay in exiting the right hand overwing exit, several passengers moved aft and used the rear door (R-2). 15 passengers were able to escape through this door. When the cabin was later inspected, a deceased flight attendant and 10 deceased passengers were found lined up in the aisle, where investigators believed that they most likely collapsed from smoke inhalation while waiting to climb out of the overwing exit.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined the probable cause of the accident to be the failure of the Los Angeles Air Traffic Facility Management to implement procedures that provided redundancy comparable to the requirements contained in the National Operational Positions Standards, and the failure of the FAA Air Traffic Service to provide adequate policy direction and oversight to its air traffic control facility managers. These failures created an environment in the Los Angeles Air Traffic Control tower that ultimately led to the failure of the local controller 2 (LC2) to maintain an awareness of the traffic situation, culminating in the inappropriate clearances and the subsequent collision of the USAir and Skywest aircraft. Contributing to the cause of the accident was the failure of the FAA to provide effective quality assurance of the ATC system.

Areas that contributed to the accident include:

NTSB Docket

- Operating procedures in the Los Angeles tower did not provide redundancy provided by flight progress strips used to monitor the progress of flights between ground control positions.

- Prior FAA evaluations did not identify absent essential redundancies at the LAX tower.

- The local controller forgot placing SKW5569 into position for takeoff on runway 24 left because of her preoccupation with another airplane. Her incorrect perception of the traffic situation was undetected because the flight progress strip seemed to match her view. If local procedures had required progress strips be processed through the ground control position, misplacement would have been detected and corrected earlier.

- The local controller did not have the Airport Surface Detection Equipment radar available; however, it probably would not have prevented the accident.

Select this link to view the detailed findings. Select this link to view the entire NTSB accident report.

Several recommendations were provided by the NTSB after conducting the investigation. They included:

- Modify Air Traffic Control procedures at the Los Angeles International Airport to segregate arrivals and departures to specific runways, and provide redundancies as intended in the National Operational Positions Standards.

- Review air traffic control procedures with regard to airport movement and potential incursions. Implement changes deemed necessary.

- Provide formal training to ATC supervisors to improve their understanding of the Technical Appraisal Program, and require interim evaluations of controller performance to better track training needs.

- Prohibit the use of cabin materials in all transport category airplanes that do not comply with the improved fire safety standards.

View the full list of recommendations.

Air Traffic Procedures

Air traffic operational procedures are contained in FAA Order 7110.65. "Air Traffic Control" This order is over 600 pages long and is not included here due to size constraints.

Airplane Design Requirements

14 CFR 25.813, Emergency exit access, (14 CFR 25.813)

14 CFR 25.853, Compartment interiors, (14 CFR 25.853)

In 1985, the FAA issued revised requirements related to cabin material flammability titled, "Improved Flammability Standards for Materials Used in Interiors of Transport Category Airplane Cabins." These new requirements applied to new designs manufactured after 1985, as well as certain retroactive requirements for all other aircraft used in air carrier service. (14 CFR 25.853 Amdt. 60 (1986)). The accident airplane, manufactured in 1985 had not yet been modified to incorporate improved cabin interior materials, since the retroactive provisions of this change to the regulations became effective upon the first replacement of the cabin interior.

Operational Requirements

14 CFR 121.215, Cabin interiors, (14 CFR 121.215)

S14 CFR 121.585, Exit Row Seating, (14 CFR 121.585)

The National Operational Position Standards (OPS) specified that flight progress strips were to be used by ground controllers. The investigation noted that, in an effort to reduce workload, the facility OPS at LAX removed this requirement on January 11, 1990, relieving the ground controller from coordinating with the local controller when intersection departures were requested. Although this reduced the ground controller's workload, it also removed system redundancies of information. The local controller was required to rely on interpreting flight crew intentions, memory, and observations of the aircraft's movement to track the progress of those entities under their control.

The accident report stated that removal of redundant systems caused "local and ground controllers [to] rely almost totally on their eyes, ears, and memory to perform their duties". Human lapses were not accounted for when allowing redundant systems to be disregarded.

In addition, the accident report also noted that performance assessments of the controller had identified concerns in critical training indicators (CTI). Although the supervisor discussed the deficiencies with the controller, he did not initiate any remedial action. The Technical Appraisal Program (TAP) intended to assist supervisors improve performance of controllers inadequately addressed what should occur when deficiencies where identified.

- A lapse in Air Traffic Control procedures that allowed a landing clearance while other traffic was on the runway awaiting takeoff clearance.

- Since the airplane was manufactured prior to 1985, it was not required to meet the interior flammability requirements of 14 CFR 25.853 until/unless the cabin interior was replaced. The NTSB cited the flammability of cabin materials as a factor in the post-accident fire.

The LAX facility management assumed that reducing the workload of ground controllers (GC) by not requiring their use of flight progress strips would not negatively impact safety. The decision to remove GC from strip marking and forwarding progress strips removed a vital redundancy element in tracking aircraft. The awareness provided by coordinating positions between GC and LC was eliminated, and backup systems were not in place.

KLM Flight 4805 and Pan American Flight 1736

On March 27, 1977, both aircraft - KLM Flight 4805, a Boeing 747-206B, and Pan American (Pan Am) Flight 1736, a Boeing 747-121, had been diverted to Los Rodeos Airport on the Spanish island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands due to a bombing at the airport at their final destination, the neighboring island of Gran Canaria. Later, when flights to Gran Canaria resumed, the aircraft collided on the runway in Tenerife as the KLM Boeing 747 initiated a takeoff while the Pan Am aircraft was using the runway to taxi.. With a total of 583 fatalities, the crash remains the deadliest accident in aviation history. All 248 passengers and crew aboard the KLM flight were killed. There were also 335 fatalities and 61 survivors on the Pan Am flight.

See accident module

Air Traffic Procedures

A general notice (GENOT) was issued on February 16, 1991, shortly after this accident, applicable to all ATC facilities stating, "Do not authorize aircraft to taxi into position and hold at an intersection between sunset and sunrise. Additionally, do not authorize an aircraft to taxi into position and hold at any time when the intersection is not visible from the tower..." This change to operational procedures was later updated and incorporated into FAA Order 7110.65, Air Traffic Organization Policy.

Policies regarding flight progress strips were also reviewed and updated, including defining what local procedures should address when strips are not used and that "No misunderstanding will occur as a result of no strip usage."

Aircraft Emergency Exits

The FAA had studied Type III exits and how size impacts evacuation prior to the LAX accident. The deaths of the USA1493 passengers that succumbed to smoke inhalation while waiting to exit was the impetus to initiate rule changes to 14 CFR 25.813. The notice for public rule-making (NPRM), to improve access to Type III exits, was issued on April 9, 1991. The final rule became effective in June 1992.

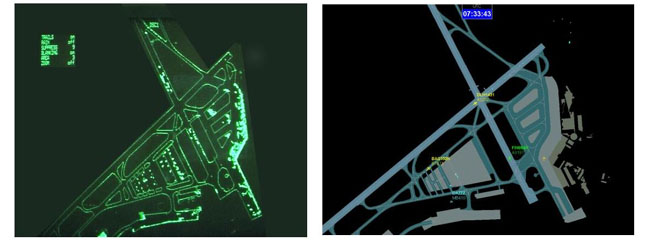

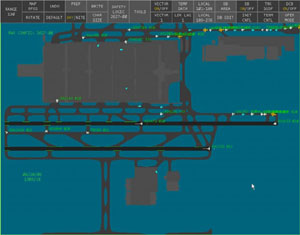

Airport Surface Detection

In addition to regulatory and policy changes, technology has impacted the radar systems used to control air traffic ground operations. In 1991 at the time of this accident, the Airport Surface Detection Equipment (ASDE) radar system was principally used to monitor ground traffic activity, especially during night hours. An example of the screen a controller would have seen in 1991 is on the left.

The picture above on the right is an example of ASDE-X, which is a recent upgrade to the system. Each aircraft is denoted with a small airplane and tagged with identifiers and flight information. Varying colors also help distinguish between runways, taxiways, and other movement/non-movement areas at the airport.

Airplane Life Cycle

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories

- Midair / Ground Incursions

- Cabin Safety / Hazardous Cargo

Groupings

- Approach and Landing

- Automation

Accident Common Themes

- Organizational Lapses

- Human Error

Human Error

Procedures in place at LAX allowed ground traffic to communicate directly with the local controller, bypassing the ground controller. The Skywest flight, having followed this process, was cleared into position on the runway, ready to make an intersection takeoff, but had not yet been cleared for takeoff. In searching for the associated progress strip, the local controller became preoccupied, and forgot the Skywest flight that was waiting on the runway. The controller subsequently cleared the USAir flight for landing, where it collided with the Skywest flight. Tower procedures did provide redundancy for lapses in controller attention or memory, allowing a human error to lead to the accident.

Organizational Lapses

The FAA national ops order addressing operational procedures for Air Traffic Control at the time of this accident included a requirement for facilities to use flight progress strips as a redundant method by which to track and sequence traffic being actively controlled by the facility, and to facilitate aircraft handoffs from one controller to another. The order specified that flight progress strips would be initiated by the ground controller, and marked, identifying the runway to which the flight is assigned. Procedures in place at the time of the accident allowed aircraft to communicate directly with the local (tower) controller, precluding communication with ground control, and bypassing a step in the use of the progress strips. This procedure required that the local controller would need to obtain the progress strip without the assistance of the ground controller. At the time of the accident, the local controller was searching for a missing progress strip, which diverted attention away from the airplane that had just been cleared into "position and hold" on the active runway. The NTSB believed that FAA adherence to the national operations order would have provided the redundancy to occasional lapses in human performance.

Pan American Airlines Flight 1736 and KLM Flight 4805

Both aircraft - KLM Flight 4805, a Boeing 747-206B, Reg. No. PH-BUF; and Pan American (Pan Am) Flight 1736, a Boeing 747-121, Reg. No. N736PA, - had been diverted to Los Rodeos Airport on the Spanish island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands due to a bombing at the airport at their final destination, the neighboring island of Gran Canaria. Later, when flights to Gran Canaria resumed, the aircraft collided on the runway in Tenerife as the KLM Boeing 747 initiated a takeoff while the Pan Am aircraft was using the runway to taxi. With a total of 583 fatalities, the crash remains the deadliest accident in aviation history. All 248 passengers and crew aboard the KLM flight were killed. There were also 335 fatalities and 61 survivors on the Pan Am flight.

See accident module

Eastern Airlines Flight 111 and Epps Air Service

On January 18, 1990, about 1904 Eastern Standard Time, an Eastern Airlines Boeing 727, flight 111, while landing on the runway in night visual conditions, collided with an Epps Air Service Beechcraft King Air AlOO, N44UE, at the William B. Hartsfield International Airport, Atlanta, Georgia. The King Air had been cleared to land on runway 26 right ahead of the Eastern flight and was in its landing roll. It was struck from behind by the B-727, which had also been cleared to land on runway 26 right. The B-727 sustained substantial damage, but none of the 149 passengers or 8 crewmembers onboard were injured. The King Air was destroyed as a result of the collision. The pilot of the King Air sustained fatal injuries, and the copilot, the only other occupant, sustained severe injuries.

Northwest Airlines Flight 1482 and Northwest Airlines Flight 299

On December 3, 1990, at 1345 Eastern Standard Time, Northwest Airlines flight 1482, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9, and Northwest Airlines flight 299, a Boeing 727, collided near the intersection of runways 09/27 and 03C/21C in dense fog at Detroit Metropolitan/Wayne County Airport, Romulus, Michigan. At the time of the collision, the B-727 was on its takeoff roll, and the DC-9 had just taxied onto the active runway. The B-727 was substantially damaged, and the DC-9 was destroyed. Eight of the 39 passengers and 4 crewmembers aboard the DC-9 received fatal injuries. None of the 146 passengers and 10 crewmembers aboard the B-727 were injured.

SAS Flight 686 and Cessna Citation 500

On October 8, 2001, while the SAS MD-87 was on takeoff roll on Runway 36R at Milano Linate Airport in Milan, Italy, a Cessna Citation taxied across the active runway in front of the SAS airplane, resulting in a collision. The MD-87 became airborne for 12 seconds, ultimately impacting a baggage handling facility on the airport. The Cessna Citation remained on the runway and was destroyed by post-impact fire. Investigators determined that due to foggy meteorological conditions, the Cessna crew had lost awareness of their position on the airport and taken an incorrect taxiway, leading to an unintentional entry onto the active runway. All passengers and crew aboard both aircraft were killed, as well as four persons inside the baggage facility that was struck by the MD-87.

Technical Related Lessons

Visual monitoring of airplane takeoffs and landings by air traffic personnel can add an additional layer of protection in order to reduce the risks of runway incursions. (Threat Category: Mid-Air/Ground Incursion)

- Situations where aircraft taxi into position and hold at runway intersections when the tower controller cannot see them can have an impact on safe airport operations. During this accident, the local controller cleared an aircraft to depart from the middle of a runway during night operations but had no direct visual monitoring capability. FAA Air Traffic Services produced a procedural change shortly after the accident through a general notice (GENOT), stating controllers were not to authorize aircraft to taxi into position and hold at an intersection between sunset and sunrise; nor were aircraft allowed to taxi into position and hold at an intersection at anytime when the tower could not see them. These procedures were later incorporated into FAA Order 7110.65.

Specific emergency briefings for passengers seated in exit rows enhance the ability to successfully evacuate passengers following an accident. It has been shown that this preparation of exit row passengers has improved evacuation capability and thereby increased passenger survivability. (Threat Category: Cabin Safety/Hazardous Cargo)

- In April 1990, prior to this accident, the FAA issued new operational rules to require operators to screen and brief passengers who are assigned seats in exit rows. The rule required operators to develop and implement plans for the required screenings and briefings. At the time of the accident, USAir had developed and implemented their plan, which included passenger screenings and briefings by gate and ticket agents, addition of placards to exit row seatbacks, and flight attendant briefings for exit row passengers. The investigation concluded that USAir's implementation of this regulatory requirement "probably resulted in more passengers escaping through the over-wing exits than otherwise would have."

Passenger survivability can be enhanced by incorporation of cabin materials that possess fire resistant capabilities. (Threat Category: Cabin Safety/Hazardous Cargo)

- In this accident, investigators determined that, except for carpeting and seat coverings, all the cabin furnishings burned. It was concluded that if the cabin furnishings had not burned so quickly, propagation of fire and smoke throughout the cabin might not have progressed as rapidly as was apparent, allowing greater opportunity for passenger evacuation and enhanced survivability. This accident underscored the importance of enhancements to cabin material flammability standards. These needed improvements had previously been addressed through rulemaking titled "Improved Flammability Standards for Materials Used in the Interiors of Transport Category Airplanes," issued in 1985. This regulation required new aircraft designs to incorporate the latest flammability standards as well as a retrofit program for the in-service fleet.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Operating procedures at control towers should provide redundancy to lapses in human performance, such as requiring flight progress strips when coordinating aircraft movement between controller positions. (Common Theme: Human Error)

- Human senses (sight, hearing) and memory are the primary means by which traffic is managed and controlled by air traffic control tower personnel. This should be augmented by processes, such as the use of flight progress strips, in order to provide redundancy to lapses in human performance. If only one method is used, normal distractions can create a lapse, causing an opportunity for poor judgment. In this case, flight progress strips were not required by the LAX facility for ground control operations. When the local controller determined a strip was missing for a specific aircraft, the distraction was not accounted for by a redundant system. Safety systems should allow for occasional human lapses.

Continuous training, evaluation, and follow-up of controller performance is a key element in maintaining the safety of the air traffic system. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapses)

- Supervisors perform over-the-shoulder evaluations of controllers to ensure that the required levels of controller and facility performance are maintained. When deficiencies are evident, corrective actions should be identified and implemented in order to maintain an adequate level of safety. In this accident the supervisor had conducted an evaluation of the LC2 controller six weeks prior to the accident and noted five performance deficiencies. The investigation noted that the controller's performance was related to facility procedures in place at LAX on the date of the accident that did not allow for lapses in judgment and decision making and removed human performance redundancies. Following the accident, local and ATC-wide procedures were modified to ensure that redundancies for human performance were in place.