Boeing 727-214 and Cessna 172/ McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 and Piper PA-28-181

This module details two accidents that were instrumental in the development and implementation of airborne collision warning systems that have, since their introduction, prevented many midair collisions.

Photo copyright Frank C. Duarte, Jr. - used with permission

Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 182, N533PS/Gibbs Flite Center, N7711G

San Diego, California

September 25, 1978

On September 25, 1978, Pacific Southwest Airlines, Inc., Flight 182, a Boeing 727-214, and a Gibbs Flite Center, Inc., a Cessna 172, collided in midair about three nautical miles northeast of Lindbergh Field, San Diego, California. Both aircraft crashed in a residential area. One hundred and thirty-seven persons, including those on both aircraft were killed; seven persons on the ground were killed; and nine persons on the ground were injured. Twenty-two dwellings were damaged or destroyed. The weather was clear, and the visibility was ten miles.

Photo copyright P. Alejandro Diaz - used with permission

The Cessna was climbing on a northeast heading and was in radio contact with San Diego approach control. Flight 182 was on a visual approach to runway 27. Its flight crew had reported sighting the Cessna, and was cleared by the approach controller to maintain visual separation and to contact the Lindbergh tower. Upon contacting the tower, Flight 182 was again advised of the Cessna's position. The flight crew no longer had the Cessna in sight. They thought they had passed it and continued their approach. The aircraft collided at an altitude of approximately 2,600 ft.

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the accident was the failure of the flight crew of Flight 182 to comply with the provisions of a maintain-visual-separation clearance, including the requirement to inform the controller when they no longer had the other aircraft in sight. Contributing to the accident were the air traffic control procedures in effect which authorized the controllers to use visual separation procedures to separate two aircraft on potentially conflicting tracks when the capability was available to provide either lateral or vertical radar separation to either aircraft.

Photo copyright Burger Collection - used with permission

Aeronaves de Mexico S.A., XA-JED/A de M Flight 498, N4891F

Cerritos, California

August 31, 1986

On August 31, 1986, about 1152 Pacific daylight time, Aeronaves de Mexico, S.A. Flight 498, a DC-9-32 with Mexican Registration XA-JED, and a Piper PA-28-181, N4891F, collided over Cerritos, California. Flight 498, a regularly scheduled passenger flight, was on an Instrument Flight Rules flight plan from Tijuana, Mexico to Los Angeles International Airport, California, and was under radar control by the Los Angeles terminal radar control facility. The Piper airplane was proceeding from Torrance, California toward Big Bear, California, under Visual Flight Rules, and was not in radio contact with any air traffic control facility when the accident occurred.

Photo copyright Barry Shipley - used with permission

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the accident was the limitations of the air traffic control system to provide collision protection through both air traffic control procedures and automated redundancy. Factors contributing to the accident were: (1) the inadvertent and unauthorized entry of the PA-28 into the Los Angeles Terminal Control Area, and (2) the limitations of the "see and avoid" concept to ensure traffic separation under the conditions of the conflict.

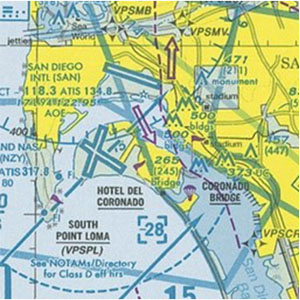

History of Flight(s) - PSA Flight 182 and Gibbs Flite Center Cessna 172

Lindbergh Field, San Diego

Cessna 172, N7711G, departed Montgomery Field, California on an instrument training flight. Since the flight was to be conducted in visual meteorological conditions, no flight plan was filed and none was required. A flight instructor occupied the right seat, and another certificated pilot, who was receiving instrument training, occupied the left seat.

The Cessna proceeded to Lindbergh Field where two practice ILS approaches to runway 9 were flown. Although the reported wind was calm, runway 27 was the active runway at Lindbergh. N7711G ended a second approach and began a climb out to the northeast. The Lindbergh tower local controller cleared the Cessna pilot to maintain VFR conditions and to contact San Diego approach control.

Accordingly, the Cessna pilot contacted San Diego approach control and stated that he was at 1,500 ft and "northeast bound." The approach controller told him that he was in radar contact, and instructed him to maintain VFR conditions at or below 3,500 ft and to fly a heading of 070°. The Cessna pilot acknowledged and repeated the controller's instruction.

Pacific Southwest Airlines, Inc., Flight 182 was a regularly scheduled passenger flight between Sacramento and San Diego, California with an intermediate stop in Los Angeles, California. The flight departed Los Angeles at 0834 on an IFR flight plan with 128 passengers and a crew of seven on board. The first officer was flying the aircraft. Company personnel familiar with the pilots' voices identified the captain as the person conducting almost all air-to-ground communications. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) established the fact that a deadheading company pilot occupied the forward observer seat in the cockpit.

Flight 182 reported to San Diego approach control at 11,000 ft, and was cleared to descend to 7,000 ft. Flight 182 then reported that it was leaving 9,500 ft for 7,000 ft and that the airport was in sight. The approach controller cleared the flight for a visual approach to runway 27, and Flight 182 acknowledged and repeated the approach clearance. Soon thereafter the approach controller advised Flight 182 that there was "traffic (at) twelve o'clock, one mile, northbound." Flight 182 answered, "We're looking."

The approach controller then advised Flight 182, "Additional traffic's twelve o'clock, three miles, just north of the field, northeast bound, a Cessna one seventy-two climbing VFR out of one thousand four hundred." The Flight 182 copilot responded, "Okay, we've got that other twelve."

Shortly after instructing the Cessna pilot to maintain VFR at or below 3,500 ft and to fly 070°, the approach controller advised Flight 182 that "traffic's at twelve o'clock, three miles, out of one thousand seven hundred." The Flight 182 first officer said, "Got 'em." and the captain informed the controller, "Traffic in sight."

In response the approach controller cleared Flight 182 to "maintain visual separation," and to contact Lindbergh tower to which Flight 182 answered, "Okay." The approach controller then advised the Cessna pilot that there was "traffic at six o'clock, two miles, eastbound; a PSA jet inbound to Lindbergh, out of three thousand two hundred, has you in sight." The Cessna pilot acknowledged, "One one golf, roger."

Photo copyright Zoltan Szalva - used with permission

As directed Flight 182 reported to Lindbergh tower that they were on the downwind leg for landing. The tower acknowledged the transmission and informed Flight 182 that there was "traffic, twelve o'clock, one mile, a Cessna."

On approach the first officer called for five flaps, and the captain asked, "Is that the one (we're) looking at?" The first officer answered, "Yeah, but I don't see him now." Flight 182 told the local controller, "Okay, we had it there a minute ago," and then, "I think he's pass(ed) off to our right." And the local controller acknowledged the transmission.

Flight 182's flight crew continued to discuss the location of the traffic.

The captain said, "He was right over there a minute ago."

The first officer answered, "Yeah." The captain informed the local controller how far they were going to extend their downwind leg, and the first officer asked, "Are we clear of that Cessna?" The flight engineer said, "Suppose to be." The captain then said, "I guess," and the forward jump seat occupant said, "I hope."

After a pause the captain said "Oh yeah, before we turned downwind, I saw him about one o'clock, probably behind us now."

The first officer called, "Gear down," and then reported, "There's one underneath," and "I was looking at that inbound there."

Boeing 727-214, Reg. No. N533PS

Source - NTSB

Concurrently, the conflict alert warning began in the San Diego Approach Control Facility, indicating to the controllers that the predicted flight paths of Flight 182 and the Cessna would enter the computer's prescribed warning parameters. The approach controller immediately advised the Cessna pilot of "traffic in your vicinity, a PSA jet has you in sight, he's descending for Lindbergh." The transmission was not acknowledged. The approach controller did not inform Lindbergh tower of the conflict alert involving Flight 182 and the Cessna because he believed Flight 182's flight crew had the Cessna in sight.

Within seconds the aircraft collided.

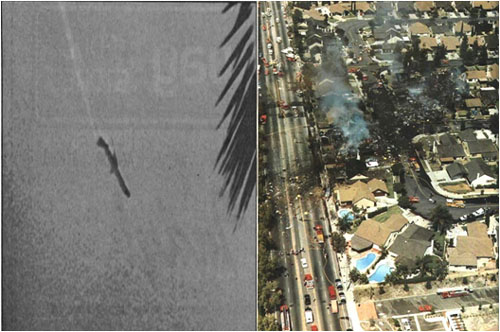

According to the witnesses, both aircraft were proceeding in an easterly direction before the collision. Flight 182 was descending and overtaking the Cessna, which was climbing in a wing-level attitude. Just before impact, Flight 182 banked to the right slightly, and the Cessna pitched nose-up and collided with the right wing of Flight 182.

The Cessna broke up immediately and exploded, while segments of fragmented wreckage fell from the right wing and empennage of Flight 182. Flight 182 began a shallow right descending turn, trailing vapor from the right wing. A bright orange fire erupted on the wing and increased in intensity as the aircraft descended. The aircraft remained in a right turn, and both the bank and pitch angles increased during the descent until impact.

The aircraft crashed during daylight hours into a residential area about three miles northeast of Lindbergh Field. Both aircraft were destroyed by the collision, in-flight and post impact fires, and ground impact. There were no survivors from either airplane. Seven persons on the ground were killed, and 22 dwellings were damaged or destroyed.

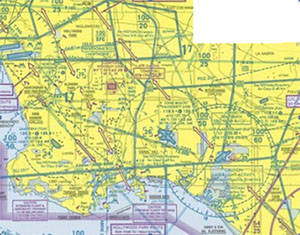

History of Flight(s) - McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 and Piper PA-28-181

On August 31, 1986, about 1141 Pacific daylight time, Piper PA-28-181, N489lF, departed Torrance, California on a Visual Flight Rules (VFR) flight to Big Bear, California. The pilot of the Piper had filed a VFR flight plan with the Hawthorne, California Flight Service Station. According to the flight plan, his proposed route of flight was direct to Long Beach, California, then direct to the Paradise, California, VORTAC, and then direct Big Bear. The proposed en route altitude was 9,500 feet. However, the pilot did not, nor was he required to, adhere to his flight plan. At 1140:36, after being cleared for takeoff, the Piper pilot told Torrance tower that he was "rolling." This was the last radio transmission received from the Piper.

According to recorded air traffic control (ATC) radar data, after leaving Torrance, the Piper PA-28 pilot turned to an easterly heading toward the Paradise VORTAC. The onboard transponder was active with a 1200 code, indicating that it was operating under visual flight rules. Post-accident investigation revealed that as the Piper proceeded on its eastbound course, it entered the Los Angeles Terminal Control Area (TCA), now designated as "Class B airspace", without requesting or receiving clearance from ATC.

Aeronaves de Mexico, S.A. (Aeromexico) Flight 498, a DC- 9-32 with Mexican registry XA-JED, was a regularly scheduled passenger flight between Mexico City and the Los Angeles International Airport (L. A. International Airport), via Loreto and Tijuana, Mexico. At 1120:00, Flight 498 departed Tijuana with 58 passengers and six crew members. As the flight proceeded toward L.A. International Airport, it was handed off to Coast Approach Control, which cleared the flight to the Seal Beach, California, VORTAC, and then to "cross one zero miles southeast of Seal Beach at and maintain seven thousand (feet)." At 1144:54 Flight 498 reported that it was leaving 10,000 feet and, at 1146:59, it was instructed to contact Los Angeles Approach Control.

At 1147:28 Flight 498 contacted the Los Angeles Approach Control's Arrival Radar-1 (AR-1) controller and reported that it was "level" at 7,000 feet. The AR-1 controller cleared Flight 498 to depart Seal Beach on a heading of 320° for the Instrument Landing System (ILS) runway, "two five left final approach course..." and Flight 498 acknowledged. At 1150:05 the AR-1 controller requested Flight 498 to reduce its airspeed to 210 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS), and the flight crew responded.

At 1150:46 the AR-1 controller advised Flight 498 that there was "Traffic, ten o'clock, one mile, northbound, altitude unknown." Flight 498 acknowledged the advisory, but they did not advise the controller that they had sighted the "traffic." (The reported traffic was not the Piper PA-28.) At 1151:04 the AR-1 controller asked the flight to reduce its airspeed to 190 KIAS and cleared it to descend to 6,000 feet. Flight 498 acknowledged the clearance. The AR-1 controller then asked Flight 498 to maintain its airspeed. The flight crew asked the controller what speed he wanted, and added that it was reducing to 190 KIAS.

At 1150:57 the controller told the flight "to hold what you have . . . and we have a change in plans for you." Flight 498 stated that it would maintain 190 KIAS.

At 1152:18 the AR-1 controller advised Flight 498 to "expect the ILS runway two four right approach . . ." Flight 498 did not acknowledge receipt of this message, and the 1152:00 radio transmission was the last communication received from Flight 498.

At about 1152:36 the AR-1 controller noticed that the Air Traffic Control computer was no longer tracking Flight 498. After several unsuccessful attempts to contact Flight 498, he notified the arrival coordinator that he had lost radio and radar contact with the flight.

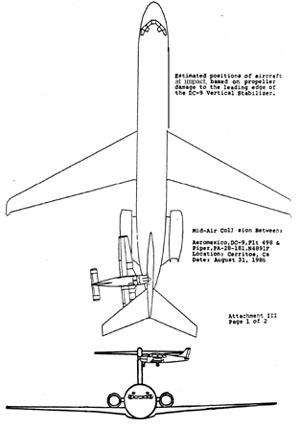

At approximately 11:52:09 Flight 498 and the Piper had collided over Cerritos, California at an altitude of about 6,560 feet. The sky was clear, the reported visibility was 14 miles, and both airplanes fell within the city limits of Cerritos. Fifty-eight passengers and six crewmembers on Flight 498 were killed as were the pilot and two passengers on the Piper. The wreckage and post impact fires destroyed five houses and damaged seven others. Fifteen persons on the ground were killed, with others on the ground receiving minor injuries.

Source - NTSB Accident Report

PSA Flight 182 and Gibbs Flite Center Cessna 172

The NTSB issued the following findings relative to the PSA accident:

- Flight 182 was cleared for a visual at Lindbergh Field.

- The Cessna was operating in an area where ATC control was approach to runway 27 being exercised, and its pilot was required either to comply with the ATC Instruction to maintain the 070° heading or to advise the controller if he was unable to do so.

- The Cessna pilot failed to maintain the assigned heading contained in his ATC instruction.

- The cockpit visibility study shows that if the eyes of the Boeing 727 pilot were located at the aircraft's design eye reference point, the Cessna's target would have been visible.

- Two separate air traffic control facilities were controlling traffic in the same airspace.

- The approach controller did not instruct Flight 182 to maintain 4,000 ft until clear of the Montgomery Field airport traffic area in accordance with established procedures contained in Miramar Order NKY.206G.

- The issuance and acceptance of the maintain-visual-separation clearance made the flight crew of Flight 182 responsible for seeing and avoiding the Cessna.

- The flight crew of Flight 182 lost sight of the Cessna and did not clearly inform controller personnel of that fact.

- The tower local controller advised Flight 182 that a Cessna was at 12 o'clock, 1 mile. The flight crew comments to the local controller indicated to him that they had passed or were passing the Cessna.

- The traffic advisories issued to Flight 182 by the approach controller at 0900:15 and by the local controller at 0900:38 did not meet all the requirements of paragraph 511 of Handbook 7110.65A.

- The approach controller received a conflict alert on Flight 182 and the Cessna at 0901:28. The conflict warning alerts the controller to the possibility that, under certain conditions, less than required separation may result if action is not, or has not been, taken to resolve the conflict. The approach controller took no action upon receipt of the conflict alert because he believed that Flight 182 had the Cessna in sight and the conflict was resolved.

- The conflict alert procedures in effect at the time of the accident did not require that the controller warn the pilots of the aircraft involved in the conflict situation.

- Both aircraft were receiving Stage II terminal radar services. Flight 182 was an IFR aircraft; the Cessna was a participating VFR aircraft. Proper Stage II services were afforded both aircraft.

- Stage II terminal service does not require that either lateral or vertical traffic separation minima be applied between IFR and participating VFR aircraft; however, the capability existed to provide this type separation to Flight 182.

- The Boeing 727 probably was not controllable after the collision.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the accident was the failure of the flight crew of Flight 182 to comply with the provisions of a maintain-visual-separation clearance, including the requirement to inform the controller when they no longer had the other aircraft in sight.

Contributing to the accident were the air traffic control procedures in effect which authorized the controllers to use visual separation procedures to separate two aircraft on potentially conflicting tracks when the capability was available to provide either lateral or vertical radar separation to either aircraft.

The complete NTSB accident report is available at the following link: PSA Accident Report

McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 and Piper PA-28-181

The NTSB issued the following findings relative to the Cerritos accident:

- The airplanes collided at a 90° angle, at an altitude of about 6,560 feet, and in visual meteorological conditions. The collision occurred inside the Los Angeles TCA.

- Both pilots were required to see and avoid the other airplane. There was no evidence that either pilot tried to evade the collision.

- The pilot of the Piper was not cleared to enter the Los Angeles TCA. His entry was inadvertent and was not the result of any physiological disablement.

- The unauthorized presence of the Piper in the TCA was a causal factor to the accident.

- The positions of the Piper were displayed on the AR-1 controller's display by, at the least, an alphanumeric triangle; however, the Piper's primary target may not have been displayed or may have been displayed weakly due to the effects of an atmospheric temperature inversion on the performance of the radar. The analog beacon response from the Piper's transponder was not displayed because of the equipment configuration at the Los Angeles TRACON.

- The AR-1controller stated that he did not see the Piper's radar return on his display, and, therefore, did not issue a traffic advisory to Flight 498. His failure to see this return and to issue a traffic advisory to Flight 498 contributed to the occurrence of the accident.

- The Los Angeles TRACON was not equipped with an automated conflict alert system which could detect and alert the controller of the conflict between the Piper PA-28 and Flight 498.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determines that the probable cause of the accident was the limitations of the air traffic control system to provide collision protection, through both air traffic control procedures and automated redundancy. Factors contributing to the accident were (1) the inadvertent and unauthorized entry of the PA-28 into the Los Angeles Terminal Control Area, and (2) the limitations of the "see and avoid" concept to ensure traffic separation under the conditions of the conflict.

The complete NTSB accident report is available at the following link: Aeromexico Report

PSA Flight 182 and Gibbs Flite Center Cessna 172

As a result of this accident, the NTSB recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration:

"Implement a Terminal Radar Service Area (TRSA) at Lindbergh Airport, San Diego, California. (Class I-Urgent Action) (A-78-77)"

"Review procedures at all airports which are used regularly by air carrier and general aviation aircraft to determine which other areas require either a terminal control area or a terminal control radar service area, and establish the appropriate one. (Class II-Priority Action) (A-78-78)"

"Use visual separation in terminal control areas and terminal radar service areas only when a pilot requests it, except for sequencing on the final approach with radar monitoring. (Class I, Urgent Action) (A-78-82)"

"Re-evaluate its policy with regard to the use of visual separation in other terminal areas. (Class II, Priority Action) (A-78-83)"

McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 and Piper PA-28-181

As stated in the NTSB accident report:

Since 1967, the Safety Board has issued 116 recommendations as a result of its investigations, special studies, and special investigations of midair or near midair collisions. A review of these 116 recommendations identified 56 that are pertinent to the accident at Cerritos.

The 56 recommendations suggested changes and/or improvements that the Safety Board believed would decrease the midair collision risk. The areas addressed in these recommendations included among others: radio communication procedures; development of ATC procedures to provide separation between high-and-low performance aircraft in high-density terminal areas; improvement of ATC radar capability; improvement of aircraft conspicuity, particularly the development and installation of anti-collision light systems and the requirement to use these lights day and night; and the development of airborne collision warning systems.

On November 4, 1969 the Safety Board convened a public hearing to investigate the subject of midair collisions. As a result of the hearing, 14 safety recommendations were sent to the FAA. Recommendations A-70-5 through -15 were sent to the FAA on February 22, 1971. These 14 recommendations addressed the area cited in the previous paragraph.

During this 19-year period, the remainder of the recommendations sent to the FAA continued to stress these areas of concern and, where warranted by facts developed during other investigations, to amplify and reiterate matter and materials contained in some of the earlier recommendations. The history of these 56 recommendations and the actions taken by the FAA in response to them is contained in detail in (Accident Report) appendix H.

As a result of this accident investigation and a review of the FAA's ongoing activities, the Safety Board reiterates the following recommendations to the FAA:

Expedite the development, operational evaluation, and final certification of the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) for installation and use in certificated air carrier aircraft. (Class II, Priority Action) (A 65 64)

Amend 14 CFR Parts 121 and 135 to require the installation of Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System equipment in certificated air carrier aircraft when it becomes available for operational use. (Class III, Longer Term Action) (A 85 65)

In addition, the Safety Board recommends that the FAA:

Implement procedures to track, identify, and take appropriate enforcement action against pilots who intrude into Airport Radar Areas (ARSAs) without the required Air Traffic Control communications. (Class 11, Priority Action) (A-87-96)

Require transponder equipment with mode C altitude reporting for operations around all Terminal Control Areas (TCAS) and within an Airport Radar Service Area (ARSA) after a specified date compatible with the implementation of Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System requirements for air carrier aircraft. Class III Longer Term Action) (A 87 97)

Take expedited action to add visual flight rules conflict alert (mode C intruder) logic to Automated Radar Terminal System (ARTS) III A systems as an interim measure to the ultimate implementation of the Advanced Automation System (AAS). (Class III, Longer Term Action) (A-87-98)

The FAA accepted and implemented all the NTSB recommendations that resulted from the Cerritos accident.

14 CFR § 91.113, Right of Way Rules, Except Water Operations

14 CFR § 91.123, Compliance with ATC Clearances and Instructions

The "see and avoid" concept has been an integral part of aviation from the beginning. Initially, it was the only mitigation available to prevent in-flight collisions, and it worked acceptably well when low-speed aircraft operated in relatively empty airspace. As airplane speeds increased, especially with the introduction of turbine powered airplanes, and air traffic volumes increased, use of the concept as an effective method of preventing collisions was called into question. At the time of the Cerritos accident, Air Traffic Control equipment and procedures had improved significantly since the previous, high-profile PSA midair collision. The fact that this accident occurred despite the ATC improvements convinced all concerned (and sensitized the public) to the inevitability of additional midair collisions if something other than "see and avoid' was not rapidly implemented as a back-up to normal ATC controlled operations.

The basic assumption of the "see and avoid" concept is that pilots can, and should be able to, see other aircraft in the vicinity, recognize when they are on a conflicting course, and effectively avoid collision. For that reason it has generally been considered in some part "pilot error" when a midair collision has occurred, with the associated implication that a properly trained pilot, operating as specified by procedure, would have been able to avoid the collision.

At the time of the PSA Flight 182/Cessna 172 accident, Air Traffic Control routinely relied on this assumed pilot capability as part of Air Traffic Control procedures (sometimes of necessity because of Air Traffic Control equipment limitations.), i.e., Air Traffic Control separation procedures were generally considered supplemental to pilot "See and Avoid" procedures, and controllers would only provide positive separation when requested and capable of doing so.

At the time of the Cerritos accident, "see and avoid" was still relied on as a means of preventing midair collisions in high traffic, positively controlled airspace.

Beginning in the early 1950's, the FAA (then CAA) began studies directed at the prevention of midair collisions. One such study concluded in 1956 that, "Only general use of proximity warning devices will substantially reduce the steadily increasing threat of midair collisions". The conclusion was based on the expected rapid introduction and use of much faster jet powered commercial airplanes along with increasing airspace traffic of all kinds. That same year a DC-7 and Lockheed Constellation collided over the Grand Canyon. That accident highlighted concerns that operational and procedural enhancement to the "see and avoid" system wouldn't be enough to prevent an increasing number of midair collisions.

PSA Flight 182 and Gibbs Flite Center Cessna 172

At the time of this accident, the FAA was in the midst of implementing Terminal Radar Service Area (TRSA) at all major airports. The FAA was, in effect, already making the changes recommended by the NTSB in recommendations A-78-77 and -78. TRSA implementation provided radar-based position and flight path information to the air traffic controller. TRSA systems combined with voice communication provided air traffic controllers the capability to provide positive separation instructions to controlled aircraft.

The FAA declined to take the actions recommended by the NTSB in A-78-82 and -83, thereby continuing the practice of reliance on "see and avoid" as the primary method of collision avoidance even when other means were available.

McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 and Piper PA-28-181

As a direct result of the Cerritos accident, in December 1987, the United States Congress enacted Public Law (P.L.) 100-223, which required the FAA to complete the development of the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) and to ensure that it was installed on all airplanes with more than 30 passenger seats by December 1991. The legislation required, by law, that the FAA expedite development and deployment of TCAS almost ten years earlier than originally planned when the program was kicked off in 1981.

To implement the provisions of this legislation, the FAA issued the TCAS Rule in January 1989, which mandated that airline aircraft with more than 30 seats be equipped with TCAS avionics no later than December 31, 1991. The European aviation authorities issued similar requirements soon thereafter.

Also as a result of the Cerritos accident, the FAA mandated that all aircraft operating within 30 miles of the busiest airports in the U. S. were required to have altitude reporting encoders, as well as transponders.

Airplane Life Cycle

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories

- Midair / Ground Incursions

Groupings

- Approach and Landing

Accident Common Themes

- Flawed Assumptions

Flawed Assumptions

Positive airspace control incorporating ground-based radar had been developed as a consequence of the Grand Canyon midair collision in 1956. Following this accident, air traffic continued to increase, leading to a point of near saturation of the air traffic system in some areas. While positive airspace control resulted in a measureable increase in air safety, there still remained a basic philosophy that placed ultimate responsibility on a flight crew to "see and avoid" any conflicting traffic. In high traffic density airport areas, which typically are also associated with high flight crew workload phases of flight, the "see and avoid" philosophy became increasingly difficult to reliably accomplish. The San Diego midair began to focus awareness that a "see and avoid" philosophy was becoming unworkable. Following that accident, the FAA initiated programs to incorporate what would become TCAS systems at an undefined future date. The occurrence of the Cerritos midair collision resulted in accelerated development, and initial deployment of TCAS, and its requirement to be operational throughout the commercial fleet at a much earlier date than had originally been planned.

List of Midair collisions between 1948 and 1978

| Date | Midair Site | Aircraft | Airline | Fatal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04/07/1948 | Northolt | DC-6 | SAL | 39 |

| 05/04/1948 | Berlin, Germany | Viking | BEA | 14 |

| 01/11/1949 | Arlington | DC-4 | EAL | 55 |

| 04/25/1951 | Key West, USA | DC-4 | Cubana | 44 |

| 02/11/1952 | New Jersey, USA | DC-6 | NAL | 26 |

| 06/30/1956 | Grand Canyon, USA | Constellation/DC-7 | TWA/UAL | 128 |

| 08/04/1957 | Moose Jaw, Canada | DC-4M | Trans Canada | 35 |

| 10/22/1958 | Nettuno, Italy | VC-7 | BEA | 31 |

| 10/06/1960 | Orly, France | Caravelle | Air Algeria | 1 |

| 12/16/1960 | New York, USA | DC-8-11/1049 | TWA/UAL | 134 |

| 01/02/1963 | Ankara, Turkey | Viscount 754D | Middle East | 104 |

| 12/05/1965 | Carmel, USA | 707/Constellation | TWA/EAL | 4 |

| 07/19/1967 | Hendersonville, USA | 727-22 | PiedMount | 82 |

| 09/03/1967 | Urbana, USA | DC-9-15 | TWA | 26 |

| 02/08/1968 | New York, USA | DC-7B | EAL | 84 |

| 04/08/1968 | Milwaukee, USA | Convair 580 | North Central | 1 |

| 09/09/1969 | Indianapolis, USA | DC-9-31 | Allegheny Airlines | 84 |

| 09/20/1969 | Hoi An, Vietnam | DC-4 | Air Vietnam | 77 |

| 01/09/1971 | Newark, NJ, USA | 707-323/Cessna 150 | AAL | 2 |

| 06/06/1971 | Duarte, California | DC-9-31 | Hughes Airwest | 50 |

| 07/31/1971 | Morioka, Japan | 727-200 | All Nippon | 163 |

| 12/20/1972 | Chicago, USA | DC-9-31, Convair | North Central/DAL | 9 |

| 05/03/1973 | Nantes, France | DC-9-32 | Iberia | 68 |

| 09/09/1976 | Sochi, USSR | Antonov 24/Yakovlev 40 | Aeroflot | 90 |

| 10/09/1976 | Zagreb, Yugoslavia | Trident/DC9 | British Airlines | 63 |

| 03/27/1977 | Tenerife, Spain | 747/747 | Pan Am/KLM | 335/248 |

| 01/03/1978 | Kano, Nigeria | F28-1000 | Nigeria Airways | 16 |

Technical Related Lessons

A collision avoidance strategy that relies primarily on the "see and avoid" safety philosophy is very much dependent upon human capabilities. In high-traffic, high pilot workload situations, this strategy has not resulted in an acceptable level of safety. (Threat Category: Midair/Ground Incursion)

- As a result of previous accidents, such as the Grand Canyon midair, it became apparent that a "see and be seen" or "see and avoid" philosophy to maintain traffic separation at cruise was no longer an option. As traffic volumes continued to increase, especially in airport departure and approach corridors, it became increasingly apparent that this philosophy, employed as a primary means to maintain traffic separation, had become less viable for the lower altitude, slower speed phases of flight as well. In airport traffic areas, high pilot workload, higher traffic density associated with airport proximity, and accomplishing other piloting duties, all interfere with "see and avoid" capabilities. These two accidents were, in part, the result of not having proper visual acquisition of conflicting traffic and having to accommodate the relatively high piloting workloads that arise during the approach and landing phases of flight.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Reliance on ground-based radar traffic control, in combination with airplane-based visual traffic acquisition and avoidance ("see and avoid") has not resulted in an acceptable level of safety. (Common Theme: Flawed Assumptions)

- The Grand Canyon midair resulted in significant gains in air safety by creating a system of positive airspace control utilizing radar two-way communications, and traffic advisories throughout the United States. As air traffic continued to increase, the continuing reliance on an airplane-based "see and avoid" collision mitigation strategy, in combination with traffic advisories, became less effective - the system essentially became saturated. During departure or arrival, an airplane must necessarily fly through an area of concentrated traffic. These phases of flight also generally subject the crew to higher workload requirements and detract from their capability to concentrate solely on traffic avoidance duties. This realization, following the Cerritos accident, led to the rapid development and deployment of airplane-based TCAS, and later systems, to enhance a crew's ability to acquire and avoid conflicting traffic and supplement the ground-based positive control systems.