Boeing 747-206B and Boeing 747-121

Photo copyright Bill Sheridan - used with permission

KLM Flight 4805, PH-BUF

Pan American Flight 1736, N735PA

Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain

March 27, 1977

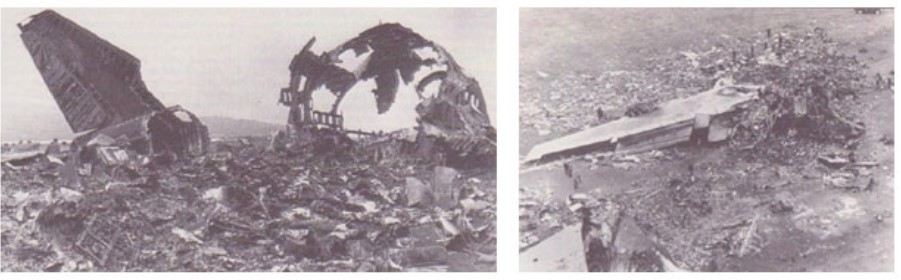

Both aircraft - KLM Flight 4805, a Boeing 747-206B, Reg. No. PH-BUF; and Pan American (Pan Am) Flight 1736, a Boeing 747-121, Reg. No. N736PA, - had been diverted to Los Rodeos Airport on the Spanish island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands due to a bombing at the airport at their final destination, the neighboring island of Gran Canaria. Later, when flights to Gran Canaria resumed, the aircraft collided on the runway in Tenerife as the KLM Boeing 747 initiated a takeoff while the Pan Am aircraft was using the runway to taxi.

Photo copyright Jean-Francois Denis - used with permission

The Spanish investigative authority, Subsecretaria de Aviacion Civil, found that the fundamental cause of the accident was the KLM captain: 1. Took off without clearance; 2. Did not obey the "stand by for take off" direction from the tower; 3. Did not interrupt take off on learning that the Pan Am aircraft was still on the runway; and 4. In reply to the KLM flight engineer's query as to whether the Pan Am aircraft had already left the runway, the KLM captain replied emphatically in the affirmative. The investigation also believed that the KLM captain's decision to take off may have been influenced by revised crew duty time limitations recently enacted by the Dutch government. The restrictions were inflexible and highly penalizing to the captain, if exceeded. With a total of 583 fatalities, the crash remains the deadliest accident in aviation history. All 248 passengers and crew aboard the KLM flight were killed. There were also 335 fatalities and 61 survivors on the Pan Am flight.

Photo copyright Benedict Pressburger – used with permission

The KLM Boeing 747, registration PH-BUF, flight number 4805, took off from Amsterdam Schipol Airport at 0900 hours (local time) on March 27, 1977, en route to Las Palmas, Canary Islands.

The Pan Am Boeing 747, registration N73PA, flight number 1736, left Los Angeles International Airport at 1729 hours (local time) on March 26, 1977, arriving at New York JFK Airport at 0117 hours (local time) on March 27, 1977. After refueling and a crew change, the aircraft departed for Las Palmas, Canary Islands at 0242 hours (local time).

Terrorist Bombing at Las Palmas

While the aircraft were en route to Las Palmas, a bomb exploded in the passenger terminal building at the airport. Due to the threat of a second explosion, the terminal building was evacuated and the airport closed. Much of the traffic arriving at Las Palmas Airport was diverted to Los Rodeos (Tenerife) Airport on Tenerife Island. For this reason, the parking area at the latter airport was crowded with airplanes.

Taxiway Congestion

Once the Las Palmas Airport had been reopened, the Pan Am crew prepared to proceed to Las Palmas. However, when they attempted to taxi to the runway, their path was blocked by the KLM airplane which, unlike the Pan Am airplane, had allowed its passengers to leave the aircraft during the delay time on the ground. All aircraft were also unable to use the parallel taxiway on account of the aircraft congestion on the main apron. The three other airplanes parked in front of the KLM airplane had already departed.

Approximately one hour later, KLM 4805 requested an estimated departure time. They said that they needed to refuel and that this would take approximately 30 minutes. They loaded 55,500 liters (approx. 14,700 gallons) of fuel. At 1656 the KLM aircraft called the tower requesting permission to taxi. A few minutes later, the Pan Am airplane called again in order to request clearance to start up its engines, and was cleared to do so.

The Tenerife-Las Palmas flight is approximately 25 minutes in duration, so the loading of 55,500 liters of fuelled investigators to believe that the KLM captain wished to avoid the difficulties of refueling in Las Palmas, with the resulting delay, because a great number of airplanes diverted from Tenerife would be arriving later. As a result, the aircraft could have returned to Amsterdam without refueling in Las Palmas.

Cockpit Voice Recorder Transmissions

At 1658 hours on March 27, 1977, when this transcript begins, the KLM and Pan Am 747s are both in queue to taxi down the runway and turn around for takeoff. The KLM aircraft is ahead of the Pan Am aircraft. Some back-and-forth communication occurs initially about what Air Traffic Control considers the best way to get the KLM plane into position for takeoff, but ultimately the controllers decide to send it taxiing straight down the runway. This portion of the transcript comes from the KLM cockpit voice recorder. (Note: In the following transcripts, RT signifies a radio transmission from the noted flight, while APP signifies a transmission from the tower controllers. If RT or APP does not appear, these statements were onboard communications between crew members, and not radio transmissions. Further, only pertinent sections have been included. Other sections not considered relevant to the events of the accident are omitted here, but may be found in the actual CVR transcript included in the accident report).

1658:14.8 KLM RT Approach KLM four eight zero five on the ground in Tenerife.

1658:21.5 APP KLM-ah-four eight zero five, roger.

1658:25.7 KLM RT We require backtrack on 12 for takeoff Runway 30.

1658:30.4 APP Okay, four eight zero five ... taxi ... to the holding position Runway 30.

Taxi into the runway and-ah-leave runway (third) to your left.

1658:47.4 KLM RT Roger, sir, (entering) the runway at this time and the first (taxiway) we, we go off the runway again for the beginning of Runway 30.

1658:55.3 APP Okay, KLM 80-ah-correction, four eight zero five, taxi straight ahead-ah-for the runway and-ah-

Photo copyright Gabe Basco – used with permission

(View Larger)

make-ah-backtrack.

1659:04.5 KLM RT Roger, make a backtrack.

1659:10.0 KLM RT KLM 4805 is now on the runway.

1659:15.9 APP four eight zero five, roger.

1659:28.4 KLM RT Approach, you want us to turn left at Charlie 1, taxiway Charlie 1?

1659:32.2 APP Negative, negative, taxi straight ahead-ah-up to the end of the runway and make backtrack.

1659:39.9 KLM RT Okay, sir.

With the KLM aircraft now taxiing down Runway 12, Air Traffic Control turns its attention to Pan Am 1736. The controllers instruct the plane to travel down the runway and then exit using one of the transverse taxiways. This would clear the way for the KLM plane to take off. This portion of the transcript comes from the Pan Am cockpit voice recorder.

1701:57.0 PA RT Tenerife, the Clipper 1736.

1702:01.8 APP Clipper 1736, Tenerife.

1702:03.6 PA RT Ah-we were instructed to contact you and also to taxi down the runway, is that correct?

1702:08.4 APP Affirmative, taxi into the runway and-ah-leave the runway third, third to your left, [background conversation in the tower].

1702:16.4 PA RT Third to the left, okay.

1702:18.4 PA 3 Third, he said.

PA? Three.

1702:20.6 APP [Th]ird one to your left.

1702:21.9 PA 1 I think he said first.

1702:26.4 PA 2 I'll ask him again.

1702:32.2 PA 2 Left turn.

The situation deteriorated further when low-lying clouds reduced visibility to the point at which neither airplane taxiing on the main runway, nor some of those located in the parking area, were visible from the tower.

1702:33.1 PA 1 I don't think they have takeoff minimums anywhere right now.

Photo copyright Gustavo Bertran – used with permission

1702:39.2 PA 1 What really happened over there today?

1702:41.6 PA 4 They put a bomb (in) the terminal, sir, right where the check-in counters are.

1702:46.6 PA 1 Well, we asked them if we could hold and-uh-I guess you got the word, we landed here...

1702:49.8 APP KLM four eight zero five how many taxiway-ah-did you pass?

1702:55.6 KLM RT I think we just passed Charlie 4 now.

1702:59.9 APP Okay ... at the end of the runway make 180 [degree turn] and report-ah-ready-ah-for ATC clearance. [background conversation in tower]

1703:09.3 PA 2 The first one is a 90-degree turn.

1703:11.0 PA 1 Yeah, okay.

1703:12.1 PA 2 Must be the third ... I'll ask him again.

1703:14.2 PA 1 Okay.

1703:16.6 PA 1 We could probably go in, it's ah...

1703:19.1 PA 2 You gotta make a 90-degree turn.

1703:21.6 PA 1 Yeah, uh.

1703:21.6 PA 2 Ninety-degree turn to get around this ... this one down here, it's a 45.

1703:29.3 PA RT Would you confirm that you want the Clipper 1736 to turn left at the third intersection? ["third" drawn out and emphasized]

1703:35.1 PA 1 One, two.

1703:36.4 APP The third one, sir, one, two, three, third, third one.

1703:38.3 PA ? One two (four).

1703:39.0 PA 1 Good.

1703:39.2 PA RT Very good, thank you.

1703:40.1 PA 1 That's what we need right, the third one.

1703:42.9 PA 3 Uno, dos, tres.

1703:44.0 PA 1 Uno, dos, tres.

1703:44.9 PA 3 Tres-uh-si.

1703:46.5 PA 1 Right.

1703:47.6 PA 3 We'll make it yet.

1703:47.6 APP ...er 7136 [sic] report leaving the runway.

1704:26.4 PA 1 That's the 90-degree.

1704:28.5 PA ? Okay.

1704:58.2 APP [KLM] 8705 [sic] and Clipper 1736, for your information, the centerline lighting is out of service. [APP transmission is readable but slightly broken]

- for determining runway visual range

Takeoff Visibility for Tenerife

Runway visibility at Tenerife was determined from several sources. An individual was located in a weather observation tower about 400 meters (1300 feet) southwest of the approach end of runway 30. (There was a similar tower at the opposite end of the runway.) This person would take weather readings and also determine both the horizontal and slant visibility he could see as he looked toward the approach path of an airplane as it landed. This person would also determine runway visibility if it exceeded the limits of the automated visibility instrument. The tower would report those values to the pilot.

The automated visibility instrument is known as a transmissometer. It was located 70 meters (200 feet) south of the runway 30 approach. This device measures the maximum horizontal distance, in kilometers or meters, at which a pilot could see either the runway surface or runway lights while rolling down the runway. Some runways have additional transmissometers at the midpoint of the runway and the far end. At Tenerife, the transmissometer visibility value at the departure end of the runway controlled the visibility required by the pilot for takeoff. If runway lights are inoperative, the required visibility value for takeoff increases. (For example, since the runway centerline lights were out of service, the Pan Am pilot required 800 meters visibility to takeoff, or about 2600 feet.)

Located near the transmissometer was a ceilometer, which measures the ceiling, or the height of the lowest layer of clouds. It uses triangulation to determine the height of a spot of light projected onto the base of a cloud.

Following the communication from the control tower regarding the inoperative runway centerline lighting, the flights acknowledged the information:

1705:05.8 KLM RT I copied that.

1705:07.7 PA RT Clipper 1736.

1705:09.6 PA 1 We got centerline markings (only) [could be "don't we"] they count the same thing as ... we need 800 meters if you don't have that centerline ... I read that on the back (of this) just a while ago.

1705:22.0 PA 1 That's two.

1705:23.5 PA 3 Yeah, that's 45 [degrees] there.

1705:25.7 PA 1 Yeah.

1705:26.5 PA 2 That's this one right here.

1705:27.2 PA 1 [Yeah], I know.

1705:28.1 PA 3 Okay.

1705:28.5 PA 3 Next one is almost a 45, huh, yeah.

1705:30.6 PA 1 But it goes...

1705:32.4 PA 1 Yeah, but it goes ... ahead, I think (it's) gonna put us on (the) taxiway.

1705:35.9 PA 3 Yeah, just a little bit, yeah.

1705:39.8 PA ? Okay, for sure.

1705:40.0 PA 2 Maybe he, maybe he counts these (are) three.

Photo copyright Manual Luis Ramos Garcia – used with permission

In the final minute before the collision, key misunderstandings occur among all the parties involved. And in the end, the KLM pilot initiates takeoff even though Air Traffic Control has not issued the proper clearance.

1705:41.5 KLM 2 Wait a minute, we don't have an ATC clearance.

KLM 1 No, I know that. Go ahead, ask.

1705:44.6 KLM RT Uh, the KLM 4805 is now ready for takeoff and we're waiting for our ATC clearance.

1705:53.4 APP KLM 8705 [sic] uh you are cleared to the Papa beacon. Climb to and maintain flight level 90 ... right turn after takeoff proceed with heading 040 until intercepting the 325 radial from Las Palmas VOR.

1706:09.6 KLM RT Ah, roger, sir, we're cleared to the Papa beacon flight level 90, right turn out 040 until intercepting the 325, and we're now (at takeoff).

When the Spanish, American, and Dutch investigating teams heard the tower recording together for the first time, no one, or hardly anyone, understood that this transmission meant that they were taking off.

1706:11.08 [Brakes of KLM 4805 are released.]

1706:12.25 KLM 1 Let's go ... check thrust.

1706:14.00 [Sound of engines starting to accelerate.]

1706:18.19 APP Okay.

Investigators questioned why Air Traffic Control would say "okay" after KLM had said that it was "at takeoff." The investigation noted that the controller may have thought that KLM meant "We're now at takeoff position." This confusion was compounded in the moments immediately following when both Air Traffic Control and Pan Am transmitted simultaneously. This caused a shrill noise in the KLM cockpit that lasted for almost four seconds and made the following three communications hard to hear in the KLM cockpit:

1706:20.08 APP Stand by for takeoff ... I will call you.

PA1 No, uh.

PA RT And we are still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736.

The following messages were audible in the KLM cockpit, causing the KLM flight engineer, even as the KLM plane had begun rolling down the runway, to question the KLM pilot:

1706:25.47 APP Ah-Papa Alpha 1736 report runway clear.

1706:25.59 PA RT Okay, we'll report when we're clear.

1706:31.69 APP Thank you.

1706:32.43 KLM 3 Is he not clear, then?

1706:34.10 KLM 1 What do you say?

1706:34.15 PA ? Yup.

1706:34.70 KLM 3 Is he not clear, that Pan American?

1706:35.70 KLM 1 Oh, yes. [emphatically]

The accident report noted that perhaps influenced by the KLM captain's ".....great prestige, making it difficult to imagine an error of this magnitude on the part of an expert pilot, both the copilot and the flight engineer made no further objections." Impact occurred about 13 seconds later. Based on the Pan Am cockpit voice recording, investigators determined that the Pan Am flight crew saw the KLM coming at them out of the fog about nine and a half seconds before impact. The Pan Am captain said, "There he is ... look at him! [expletives deleted] is coming!" and his copilot yells, "Get off! Get off! Get off!" The Pan Am pilot accelerates the engines but not in sufficient time to avoid the collision. At 1706:47.44, the collision occurred.

Duty Time and Rest Regulations

At the time of the accident, investigators learned that the Dutch rules regarding duty time limits had recently been changed. Prior to this, the captain had a great deal of discretion in extending his crew's duty time in order to complete the scheduled service. However, new rules imposed absolute rigidity with regard to duty time limits. The captain was forbidden to exceed these limits and, in the event that duty times were exceeded, could be prosecuted under the law.

Moreover, until December 1976, it was relatively easy to adjust the duty time by taking only a few factors into account. The investigation concluded that the new calculation methods were so complicated that, in practice, it was impossible for a flight crew to calculate adjustments in the cockpit. For this reason, KLM management strongly recommended that they be contacted in order to determine the adjusted duty time.

This was the situation on the day of the accident. The investigators noted that during the delay at Tenerife, the KLM captain, using HF radio, contacted the company's operations office in Amsterdam. He was told that if he was able to takeoff before a certain time it seemed that there would be no problems with duty time. However, if there was any risk of exceeding the limit, the company would send a telex to Las Palmas. This uncertainty of the crew as to their duty time limit was found by the accident investigation to be an important psychological factor.

Human Factors

The investigation noted a number of factors that may have influenced the decisions made by the KLM crew. These are listed in the report as: (quoted directly from the report, as indicated.)

"...from a careful listening to the KLM CVR that although cockpit operation was correct and the check-lists were adequately kept, there was some feeling of anxiety regarding a series of factors, which were: the time margin remaining to them, to the point of straining the allowable limit of their duty time; the poor and changing visibility which, especially as the runway centre lights were not operative, might prevent the possibility of take-off within the weather limits required by the company; the inconvenience for the passengers, etc."

'It is also observed that, as the time for take-off approached, the captain - perhaps on account of all these worries - seemed a little absent from all that was heard in the cockpit. He enquired several times, and after the copilot confirmed the order to backtrack, he asked the tower if he should leave the runway by C-l, and subsequently asked his copilot if he should do so by C-4. On arriving at the end of the runway, and making a 180-degree turn in order to place himself in take-off position, he was advised by the copilot that he should wait as they still did not have an ATC clearance. The captain asked him to request it, which he did, but while the copilot was still repeating the clearance, the captain opened the throttle and started to take off.'

'Then the copilot, instead of requesting take-off clearance or advising that they did not yet have it, added to his read-back, "We are now at take-off." The tower, which was not expecting the aircraft to take off as it had not given clearance, interpreted the sentence as, "We are now at take-off position"(1) and the controller replied: "Okay, ... stand by for take-off ... I will call you." Nor did the Pan Am on hearing the "We are now at take-off", interpret it as an unequivocal indication of take-off. However, in order to make their own position clear, they said, "We are still taxiing down the runway." This transmission coincided with the "Stand by for take-off ... I will call you", causing a whistling sound in the tower transmission and making its reception in the KLM cockpit not as clear as it should have been, even though it did not thereby become unintelligible.'

‘The communication from the tower to the PAA requested the latter to report when it left the runway clear. In the cockpit of the KLM airplane which was taking off, nobody at first confirmed receiving these communications (Appendix 5) until the Pan Am airplane responded to the tower's request that it should report leaving the runway with an "Okay, we'll report when we're clear." On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer asked: "Is he not clear then?" The captain didn't understand him and he repeated: "Is he not clear that Pan American?" The captain replied with an emphatic "Yes" and, perhaps influenced by his great prestige, making it difficult to imagine an error of this magnitude on the part of such an expert pilot, both the copilot and the flight engineer made no further objections. The impact took place about thirteen seconds later.'

"(1) When the Spanish, American and Dutch investigating teams heard the tower recording together and for the first time, no-one, or hardly anyone, understood that this transmission meant that they were taking off."

Another factor identified in the investigation was the low-lying clouds that descended upon the airport just prior to the accident. Visibility both before and during the accident was variable. While runway visibility was reported to be 2 to 3 kilometers 17 minutes prior to the accident, visibility reduced to just 300 meters 12 minutes later. Just after the accident, visibility had improved to one kilometer. The investigators concluded that the changing visibility caused "...an increase in subconscious care to the detriment of conscious care, part of which was already focused on takeoff preparation (completing of checklists, taxiing with reduced visibility, etc.)."

The investigation also concluded that the KLM crew also had a "...fixation on what was being seen (increasing fog) with a consequent diminished capacity to assimilate what was heard." The crew was also fixated "...on trying to overcome the threat posed by a further reduction of the already precarious visibility. Faced with this threat, the way to meet it was either by taking off as soon as possible, or by testing the visibility once again and possibly refraining from taking off (a possibility which certainly must have been considered by the KLM captain)."

The investigation also concluded that the KLM crew probably felt a certain level of relaxation following the execution of a "...difficult 180 degree turn, which must have coincided with a momentary improvement in the visibility (as proved by the CVR, because which shortly before arriving at the approach end of the runway they turned off the windshield wipers), the crew must have felt a sudden feeling of relief which increased their desire to finally overcome all of the ground problems: the desire to be airborne."

Accident Memorial

On March 27, 2007, 30 years after the disaster, a first time ever official international memorial service for the largest aviation disaster in history was held on the initiative of the Foundation for the Surviving Relatives of the Tenerife Disaster.

The international commemoration consisted of two parts: a memorial service at the Auditorio de Tenerife in the capital Santa Cruz; and the unveiling of an international monument on Mount Mesa Mota in the municipality of San Cristóbal de La Laguna. The ceremonies were attended by Dutch and American next of kin and survivors, as well as Spanish aid workers and others who were involved in the disaster. The monumental art work, designed by renowned Dutch artist Rudi van de Wint, is an 18-meter spiral stair case, named Stairway to Heaven, of which the steps appear to move endlessly upward into infinity, but are cut off suddenly.

Acknowledgement

The FAA wishes to thank Captain Robert L. Bragg, First Officer on Pan American Flight 1736, for his assistance in the preparation and review of this "Lessons Learned from Transport Airplane Accidents" material. Captain Bragg began his flying career with the United States Air Force in 1959, and transitioned to a commercial pilot in 1964 with Pan American, and in 1987 with United Airlines. During his flying career, he has flown many different types of airplanes ranging from the DC-6, to the B747-400. He logged more that 33,000 hours, and after leaving flying duties in 2000, continued giving lectures and providing aviation consultant services to several major networks. For his efforts in assisting fellow crew members and passengers of the Tenerife crash, he received the United States President's Award for heroism, FAA's Achievement Award, and the Flight Safety Foundations Award for actions during an accident.

The Spanish Accident Board found that the fundamental cause of this accident was the fact that the KLM captain:

- Took off without clearance.

- Did not obey the "stand by for take-off" from the tower.

- Did not interrupt take-off when Pan Am reported that they were still on the runway.

- In reply to the flight engineer's query as to whether the Pan Am airplane had already left the runway, replied emphatically in the affirmative.

An explanation may be found in a series of factors which possibly contributed to the occurrence of the accident.

- A growing feeling of tension as the problems for the captain continued to accumulate. He knew that, on account of the strictness in the Netherlands regarding the application of rules on the limitation of duty time, if he did not take off within a relatively short span of time he might have to interrupt the flight - with the consequent upset for his company and inconvenience for the passengers. Moreover, the weather conditions in the airport were getting rapidly worse, which meant that he would either have to take off under his minima or else wait for better conditions and run the risk of exceeding the aforementioned duty-time limit.

- The special weather conditions in Tenerife must also be considered a factor in itself. What frequently makes visibility difficult is not actually fog, whose density and therefore the visibility which it allows, can be fairly accurately measured, but rather layers of low-lying clouds, blown by the wind and thus a cause of sudden and radical changes in visibility. The latter can be zero m at certain moments and change to 500 m or 1 km in a short span of time, only to revert to practically zero a few moments later. These conditions undoubtedly make a pilot's decisions regarding take-off and landing operations much more difficult;

- The fact that two transmissions took place at the same time. The "stand by for take-off ... I will call you" from the tower coincided with Pan Am's "we are still taxiing down the runway," which meant that the transmission was not received with all the clarity that might have been desired. The whistling sound which interfered with the communication lasted for about three seconds.

The Board also stated that the following must also be considered factors which contributed to the accident:

- Inadequate language. When the KLM copilot repeated the ATC clearance, he ended with the words, "We are now at take-off." The controller, who had not been asked for take-off clearance, and who consequently had not granted it, did not understand that they were taking off. The "Okay" from the tower, which preceded the "stand by for take-off" was likewise incorrect - although irrelevant in this case because take-off had already started about six and a half seconds before.

- The Pan Am airplane not leaving the runway at the third intersection. This airplane should, in fact, have consulted with the tower to find out whether the third intersection referred to was C-3 or C-4, if it had any doubts, and this it did not do. However, this was not very relevant either since the Pan Am airplane never reported the runway clear but, on the contrary, twice advised that it was taxiing on it.

- Unusual traffic congestion. This congestion obliged the tower to carry out taxiing maneuvers which, although statutory, as in the case of having airplanes taxi on an active runway, are not standard and can be potentially dangerous.

The Board also found as contributing to the accident, but not considered direct factors in the accident: the bomb incident in Las Palmas; the KLM refueling; the latter's take-off at reduced power; etc.

View the entire Spanish accident report.

The Spanish Accident Board made three recommendations:

- Place of great emphasis on the importance of exact compliance with instructions and clearances.

- Use of standard, concise and unequivocal aeronautical language.

- Avoid the word "take-off" in the ATC clearance and adequate time separation between the ATC clearance and the take off clearance.

Work and Rest Regulations for Flight Crews, December 1976, Dutch law.

Note: During the preparation of this "Lessons Learned" material, attempts were made to acquire the text of the 1976 Dutch Law regarding crew duty times. All attempts were unsuccessful, and as a result, it is not included here.

In December 1976, the Dutch government changed the law, "Work and Rest Regulations for Flight Crews." As a direct result of this change, computation of limits on duty time and required rest were very complicated and difficult to determine in the cockpit (KLM urged crews to contact the company when this computation was needed). In addition, the captain no longer had the option to extend duty time at his discretion. Finally, if duty time limits were exceeded, the captain could be subject to fines, imprisonment, or the loss of his license.

- Assumption on the part of the KLM captain that the KLM flight was cleared for take off.

- Assumption that the Pan Am flight had cleared the runway.

This accident was considered to be entirely the result of operational errors. FAA's "Call to Action" initiative in August 2007 was developed, in part, to mitigate the threat of runway incursion incidents and accidents. The Tenerife accident was, in part, instrumental in the development of this initiative.

As this accident was considered entirely the result of operational errors, no airworthiness directives were issued by any authority.

Airplane Life Cycle

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories

- Crew Resource Management

- Midair / Ground Incursions

Groupings

- N/A

Accident Common Themes

- Human Error

- Unintended Effects

Human Error

Errors were made by numerous individuals. The most important of these was the KLM captain's decision to takeoff with another aircraft on the active runway.

- The KLM captain, in his haste to depart, did not wait for takeoff clearance before beginning his takeoff roll.

- The tower controller did not immediately understand the KLM first officers' statement "We are now at takeoff" to mean that the KLM aircraft had started its takeoff. When he did realize this he stated, "Stand by for takeoff ... I will call you." However, this was not clearly heard in the KLM cockpit.

- The Pan Am crew did not exit the runway via the taxiway given by the tower controller, Taxiway Charlie Three. Instead the crew may have assumed, due to the configuration of the airport, that the controller meant for them to exit via the more easily navigated fourth taxiway.

Unintended Effects

Previous duty time regulations allowed a captain some flexibility in extending duty time. A new Dutch law, enacted in 1976, removed a crew's flexibility in compliance. Further, if duty time were exceeded, a captain could be held liable for criminal prosecution. The law had originally been intended as a means to improve safety by assuring that flight crews were adequately rested, remained alert for the duration of a flight, and capable of good decision making. The unintended effect, in the case of the Tenerife accident, was exactly the opposite. According to the accident report, the captain became preoccupied with duty time limitations, and was approaching a time deadline, after which the flight would have to be cancelled. The investigation concluded that his preoccupation with not exceeding the deadline may have resulted in his poor decision making, and led to a series of unsafe actions that resulted in the accident.

February 1, 1991, Runway Collision between USAir Flight 1493, Boeing 737-300, and Skywest Flight 5569, Fairchild Metroliner, at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), Los Angeles, California.

Technical Related Lesson

Clearances to move about an airport, especially clearances to take off or land, should be clear and unambiguous, and compliance should be exact. (Threat Category: Midair/Ground Incursions)

- In this accident, traffic at the airport was unusually congested, requiring the use of all available taxiways, and even the runway to expedite movement of traffic for takeoff. Rapidly changing and deteriorating weather further complicated traffic movement on the ground. Both the KLM and Pan Am flights were back taxiing on the runway at the same time in order to accommodate the desired imminent departure of both flights. Deteriorating visibility created some confusion on the part of the Pan Am crew as to the proper taxiway at which to exit the runway, and KLM had accomplished a 180-degree turn at the end of the runway and was waiting in position for takeoff clearance. Upon receiving a departure clearance, the KLM flight misunderstood this as a takeoff clearance and began their takeoff roll with Pan Am still on the runway. Had the KLM crew questioned the clearance, or queried the control tower as to the location of the Pan Am flight, the accident may have been avoided.

Flight crew communications regarding airplane safety readiness should be open and effective. Each crew member must clearly give and receive communication in such a way that the flight safety decisions represent the best product of this open, two-way communication. (Threat Category: Crew Resource Management)

- In this accident, the flight engineer apparently heard the Pan Am crew state that they would report to the tower when they were clear of the runway, and were therefore still on the runway. The flight engineer then asked the KLM captain, "Is he not clear, then?" The KLM captain replied, "What do you say?" and the flight engineer reiterated, "Is he not clear, that Pan American?" The captain responded with an emphatic "Oh, yes" and continued the takeoff. The impact occurred 13 seconds later. It was believed by the investigators that the other crew members did not further question the captain's actions due to his senior position within the company. When the flight engineer perceived a miscommunication with the clearance, his lack of insistence that the captain listen to him resulted in the captain proceeding with the takeoff, and the resulting accident.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Deviations from operations or procedures that are considered normal, or routine, increase the risks for human errors of all kinds. When it is necessary to deviate from normal operations, extra vigilance and strict adherence to proper procedures should be emphasized. (Common Theme: Human Error)

- A bombing at the Las Palmas airport, the intended destination of both the KLM and Pan Am flights, as well as many others, caused a diversion to and an unusual situation at the Tenerife airport. Everyone involved, from each flight to the air traffic controllers, were forced to compensate for the unusual circumstances. In a cascading series of deviations from normal, routine events, confusion in the cockpits of both the KLM and Pan Am flights and in the control tower led to a series of errors that resulted in the accident.

Regulatory standards should be sufficiently flexible to allow deviation in special circumstances, without compromising safety. Application of an appropriate alternative can result in the level of safety intended by the regulation. (Common Theme: Unintended Effects)

- A revised Dutch regulation, imposing new limitations on crew duty time, was discussed in the accident report and was concluded to have had an influence on the decision-making of the KLM captain. Previous duty time regulations allowed a captain some flexibility in extending the crew's duty time. The new law, enacted in December 1976, was inflexible, and compliance was difficult. Furthermore, if duty times were exceeded, a captain could be liable for criminal prosecution. The law had originally been intended to prevent negligence among flight crews in adhering to duty time requirements. It was originally viewed as a means to improved safety by assuring that flight crews were adequately rested and remained alert for the duration of a flight. The unintended effect, in the case of the Tenerife accident, was exactly the opposite. According to the accident report, the captain became preoccupied with duty time limitations and was approaching a time deadline, after which the flight would have to be cancelled. The investigation concluded that his preoccupation with not exceeding the deadline may have influenced his decision making, and led to a series of unsafe actions that resulted in the accident.