Beechcraft Bonanza 35

Dwyer Flying Service, N3794N

Clear Lake, Iowa

February 3, 1959

At approximately 0100 on February 3, 1959, a chartered Beechcraft Model 35 Bonanza, N3794N, crashed approximately five miles northwest of the Mason City Municipal Airport, Mason City, Iowa. The flight destination had been planned to be Fargo, North Dakota, an air distance of approximately 300 miles. The pilot and three passengers were killed, and the aircraft was destroyed.

The aircraft took off into deteriorating weather, with light snow beginning, a falling barometer, and lowering ceiling and visibility. After initially heading south, the airplane turned to the northwest and climbed to an estimated altitude of 800 feet. Just prior to the crash, and from a distance of about five miles, a witness observed the taillight of the aircraft begin a gradual descent until it disappeared. Subsequent attempts to contact the airplane by radio were unsuccessful. The wreckage was found in a field later that morning.

The Civil Aeronautics Board determined that the probable cause of the crash was, "the pilot's unwise decision to embark on a flight which would necessitate flying solely by instruments when he was not properly certificated or qualified to do so. Contributing factors were serious deficiencies in the weather briefing and the pilot's unfamiliarity with the instrument which determines the attitude of the aircraft."

History of Flight

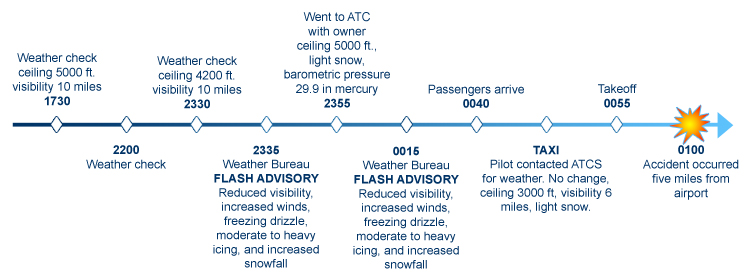

The accident flight was a charter flight from Mason City, Iowa to Fargo, North Dakota. Prior to the flight, and beginning at approximately 1730 on February 2, the pilot began checking weather information for the route of flight. Weather briefings included the local Mason City area, Minneapolis, Redwood Falls, and Alexandria, Minnesota, and the terminal forecast for Fargo. During this initial check, the pilot was advised that all stations were reporting ceilings of at least 5,000 feet and visibility of ten miles or more. The Fargo terminal forecast indicated the possibility of light snow showers after 0200 February 3 and passage of a cold front at about 0400. The pilot was also made aware that a later terminal forecast would be available at 2300. At 2200, and again at 2330, the pilot repeated his weather checks. During the 2330 check, he was advised that the stations en route were reporting ceilings of at least 4,200 feet with visibility still ten miles or greater. Light snow was reported at Minneapolis. The cold front previously forecast to pass Fargo at 0400 was now forecast to pass there at 0200. The Mason City weather was a measured ceiling of 6,000 feet, overcast skies, and visibility of greater than 15 miles. Temperature was reported as 15 degrees F with a dew point of 8 degrees F. Wind was from the south at 25 to 32 knots. Barometric pressure was 29.96 inches of mercury.

At 2355, the pilot made a final weather check. The local weather had deteriorated in that the ceiling had lowered to 5,000 feet, light snow was falling, and the barometric pressure had fallen to 29.90 inches of mercury. Winds remained at 20 knots with gusts to 30 knots. Additionally, at 2335, and again at 0015, the U. S. Weather Bureaus in Minneapolis and Kansas City issued flash weather advisories that called for further deterioration of the weather along the planned route of flight, including reduced visibility, increased winds, freezing drizzle, moderate to heavy icing, and increased snowfall. The pilot was not informed of either advisory during the final weather briefing (by radio) just prior to takeoff at 0055.

The passengers arrived at the airport at about 0040 and the aircraft was prepared for takeoff. During taxi, the pilot made one more weather check via radio. En route weather had not changed substantially, but the pilot was advised that local weather had continued to deteriorate, with ceilings having lowered to 3,000 feet with the sky obscured, visibility of six miles, and a further fallen barometric pressure of 29.85 inches of mercury. Winds remained as previously measured at 20 knots with gusts to 30 knots.

The charter flight performed a normal takeoff at 0055, and once airborne made a left 180-degree turn and climbed to approximately 800 feet. After passing the airport to the east, the airplane then turned in a northwesterly direction, generally along the planned route of flight. Through most of the flight the tail light of the aircraft was plainly visible to a witness, who was watching from a platform outside the Mason City Airport control tower. When the airplane was about five miles from the airport, the witness saw the tail light of the aircraft gradually descend until out of sight. At approximately 0100, when the pilot did not file his flight plan by radio as he had planned prior to takeoff, repeated unsuccessful attempts were made by control tower personnel to contact the airplane.

After an extensive air search, wreckage of the flight was sighted in an open farm field at approximately 0935 that morning. All occupants had been fatally injured and the aircraft was completely destroyed. The field in which the aircraft was found was level and covered with about four inches of snow.

The accident occurred in a sparsely populated area, and there were no witnesses to the actual crash. By examination of the wreckage, investigators determined that the first impact with the ground was made by the right wing tip while the aircraft was in a steep right bank, and in a nose-low attitude. Investigators further determined that the aircraft was traveling at high speed on a heading of 315 degrees. The debris field extended over a distance of 540 feet, ending with the main wreckage lying against a barbed wire fence. The three passengers had been thrown clear of the wreckage. The pilot was found in the cockpit. The two front seat safety belts as well as the middle belts in the rear seat were torn free from their attach points. The two rear outside belt ends remained attached to their respective fittings, but the buckle of one was broken.

Although the aircraft was badly damaged, investigators were able to establish certain facts. There had been no fire. All pieces of the airplane were found at the wreckage site. There was no evidence of inflight structural or flight control failures, and the landing gear was retracted at the time of impact.

During the course of the investigation, the damaged engine was disassembled and examined. Investigators found no evidence of engine malfunction or failure in flight. Both propeller blades were broken at the hub, leading investigators to conclude that the engine had been producing power at impact. Propeller blade pitch was in the cruise range.

Despite the damage to the cockpit, investigators were also able to determine: (excerpted from the accident report)

- "Magneto switches were both in the "off" position.

- Battery and generator switches were in the "on" position.

- The tachometer r.p.m. needle was stuck at 2200.

- Fuel pressure, oil temperature, and pressure gauges were stuck in the normal or green range.

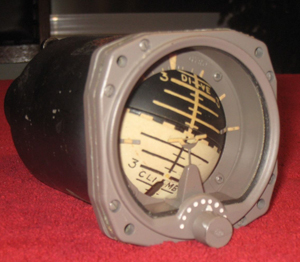

- The attitude gyro indicator was stuck in a manner indicative of a 90-degree angle.

- The rate of climb indicator was stuck at 3,000-feet-per-minute descent.

- The airspeed indicator needle was stuck between 165-170 mph.

- The directional gyro was caged.

- The omni selector was positioned at 114.9, the frequency of the Mason City omni range.

- The course selector indicated a 360-degree course.

- The transmitter was tuned to 122.1, the frequency for Mason City.

- The Lear autopilot was not operable."

The Civil Aeronautics Board ultimately concluded that this accident was the result of several factors. First, the pilot was not qualified to operate an airplane in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC). The Air Service from which the airplane was chartered was approved to operate only in visual meteorological conditions; however, the flight was undertaken in conditions where it was likely that instrument conditions would be encountered. The attitude indicator installed on the accident aircraft operated in a manner that presented attitude information in a format that was opposite to other aircraft in which the pilot was familiar. Investigators believed that after encountering instrument flight conditions, he became confused by the instrument, contributing to a loss of control of the airplane. Finally, investigators criticized the weather briefings and speculated that had the weather briefings been more complete, the pilot might have considered delaying or cancelling the flight.

Photo copyright Mason City Municipal Airport Manager's Office - used with permission

Weather

Investigators cited the weather, in combination with the pilot's lack of qualification to fly in instrument meteorological conditions, as a primary contributing factor in the occurrence of this accident. Prior to the accident, weather conditions had been deteriorating, but remained such that flight by visual flight rules (VFR) remained technically possible. Reported ceilings and visibility remained adequate for VFR flight. For several hours prior to the flight, the pilot repeatedly checked the weather at the Air Traffic Communications Station (ATCS). Local weather reports and forecasts remained relatively stable in terms of ceilings and visibility along the route of flight, but actual conditions were slowly deteriorating in Mason City. The overall weather picture showed a cold front extending from the northwestern corner of Minnesota through central Nebraska with a secondary cold front through North Dakota. Weather forecasts called for widespread snow showers associated with these fronts as they moved east. Temperatures along the planned route were below freezing at all levels with an inversion between 3,000 and 4,000 feet. Moisture was present through 12,000 feet, which, in combination with the freezing temperatures, was conducive to icing conditions which were predicted to be moderate to heavy at times. Winds were reported to be 30 to 50 knots.

Photo copyright Mason City Municipal Airport Manager's Office - used with permission

At 2335, about 90 minutes prior to the flight, the U. S. Weather Bureau at Minneapolis issued a flash weather advisory containing the following information: "Flash Advisory No. 5 A band of snow about 100 miles wide at 2335 from extreme northwestern Minnesota, northern North Dakota through Bismarck and south-southwestward through Black Hills of South Dakota with visibility generally below two miles in snow. This area or band moving southeastward about 25 knots. Cold front at 2335 from vicinity Winnipeg through Minot, Williston, moving southeastward 25 to 30 knots with surface winds following front north-northwest with 25 to gusts of 45. Valid until 0335."

At 0015, about 40 minutes prior to the flight, the U. S. Weather Bureau at Kansas City, Missouri also issued a flash advisory consisting of the following information: "Flash Advisory No. 1. Over eastern half of Kansas ceilings are locally below one thousand feet, visibilities locally two miles or less in freezing drizzle, light snow and fog. Moderate to locally heavy icing areas of freezing drizzle and locally moderate icing in clouds below 10,000 feet over eastern portion Nebraska, Kansas, northwest Missouri and most of Iowa. Valid until 0515."

The investigation established that neither of these advisories was transmitted to the pilot. Investigators also speculated that if the pilot had been aware of these advisories, and of the rate at which local conditions were deteriorating, he might have elected to cancel or delay the flight. The investigation further stated that the failure to draw these advisories to the attention of the pilot and to emphasize their importance could readily lead the pilot to underestimate the severity of the weather situation.

Additionally, at takeoff, the Mason City barometer was falling, the ceiling and visibility were rapidly deteriorating, and light snow had begun to fall. The investigation further concluded that surface winds and winds aloft were so high that a pilot could reasonably have expected to encounter adverse weather during the estimated two-hour flight.

Snow had already begun to fall in Minneapolis, and the general forecast along the intended route was for continued deteriorating conditions. The accident report states, "Considering all of these facts and the fact that the company was certificated to fly in accordance with visual flight rules only, both day and night, together with the pilot's unproved ability to fly by instrument, the decision to go seems most imprudent." The investigation concluded that with the conditions existing at takeoff, the flight would have almost immediately encountered instrument flight conditions for which the pilot was not properly qualified.

View Larger

Attitude Indicator

The attitude indicator, a Sperry F3 attitude gyro, was cited by investigators as having been a possible contributor to the accident. The accident aircraft was equipped with high and low frequency radio transmitters and receivers, a Narco omnigator, Lear autopilot (only recently installed and not operable), and a full panel of instruments capable of being used for instrument flying, including the Sperry F3 attitude gyro.

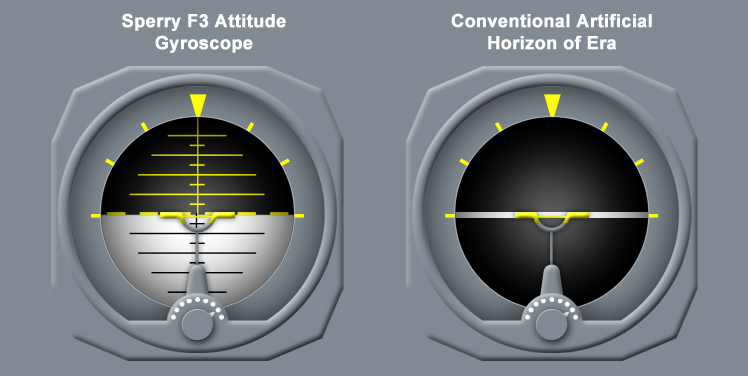

A conventional artificial horizon provides a direct indication of the bank and pitch attitude of the aircraft. The airplane is symbolically depicted by a miniature aircraft and is displayed against a horizon bar (also referred to as a pitch bar.) The operating portion of the instrument is a gimbal mounted ball that rotates as the airplane changes attitude in either the pitch or roll axis. As installed in the accident airplane, based on similar installations of the era, the artificial horizon would have been a simple black ball with an indicated horizon line. At extreme attitudes, (pitch or roll attitudes in excess of approximately 60 degrees) the internal gimbals impinge on instrument case structure and cause the gyro to "tumble," and display incorrect attitude information. Following an event where the gyro tumbled, it can be reset by caging and then uncaging the instrument. A more complete description of a conventional instrument of the time was published in Air Tech Magazine in May 1943, and is available at the following link: (Air Tech Magazine Article).

On more modern instruments, the ball is typically colored brown, or a darker color, on the lower half of the instrument face, to indicate the ground, and blue, or a lighter color, on the upper half, to indicate the sky. The instrument face is also graduated in markings, referred to as a "pitch ladder" to indicate the pitch attitude above or below level flight. For example, if the airplane enters a climb, the airplane symbol appears to climb up the pitch ladder. For a descent, or a pitch attitude below level flight, the airplane symbol moves down the pitch ladder. In fact, the gimbal mounted ball is rotating behind the airplane symbol, but the indication is such that it appears the airplane symbol is moving relative to the background.

The Sperry F3 gyro, as installed on the accident aircraft, also provided a direct indication of the bank and pitch attitude of the aircraft, but was mechanized in such a way that pitch indications were exactly opposite from those of a conventional artificial horizon. Color shading was also opposite from a conventional instrument, dark in the upper half and bright in the lower half. Pitch indication was such that if the airplane was pitched nose-up, the airplane symbol would appear to move down the instrument face, rather than up as in a conventional instrument. A more complete description of this attitude instrument was included in a March 1945 article in Flight Magazine. That article can be viewed at this link: (Flight Magazine Article).

Following introduction into service, experience with the Sperry F3 clearly indicated that pilot confusion was common during the transition period of initial use, or when alternating between airplanes equipped with conventional and F3 instruments. Investigators concluded that since the accident pilot had received his instrument training in aircraft equipped with conventional artificial horizons, and since the Sperry F3 is opposite in its display of pitch attitude, it is probable that the reverse sensing could at times result in reverse control action. This would be especially true of instrument flight conditions requiring a high degree of concentration, as would be the case when flying in instrument conditions in turbulence without a copilot. Examination of the wreckage revealed that the directional gyro (heading indicator) was caged (not operating and locked at a fixed heading) and investigators deemed it possible that it was never used during the short flight. If the directional gyro were caged throughout the flight, this could have added to the pilot's confusion.

An animation of the accident flight path and a comparative illustration between a Sperry F3 attitude gyro and a conventional artificial horizon is available below:

Spatial Disorientation

While not cited by investigators as a contributor in this event, spatial disorientation is a common factor in this type of accident. Spatial disorientation, either as a primary accident cause or as a contributor to loss of control accidents is important to understand. The FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) has issued a publication explaining this phenomenon and its effect on pilots. This publication can be viewed at the following link: (Spatial Disorientation).

CAMI has also produced a full-length video on the subject of special disorientation, and the dangers it can pose during instrument flight. The video can be viewed below:

Accident Memorial

In 1989, a stainless-steel monument that depicts a guitar and a set of three records bearing the names of the three celebrities killed in the accident was placed at the accident site. In February 2009, a second memorial for the pilot, depicting a pair of pilot wings, was also placed at the accident site. The two monuments are within a few feet of each other and near the site where the airplane wreckage was found.

Conclusion

The investigation concluded that "At night, with an overcast sky, snow falling, no definite horizon, and a proposed flight over a sparsely settled area with an absence of ground lights, a requirement for control of the aircraft solely by reference to flight instruments can be predicated with virtual certainty."

The accident report states that the pilot, when just a short distance from the airport, was confronted with this exact situation. Instrument fluctuations resulting from the gusty winds would have forced the pilot to focus his attention on the attitude gyro, an instrument with which he was not completely familiar. He was unaccustomed to the reversed pitch display of the attitude gyro, and therefore could have become confused when trying to respond to gust-induced flight path instabilities. The investigation further cited the inadequate weather briefings that should have identified the significantly adverse conditions for the flight.

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) did not issue formal findings. However, the accident report itself contains a number of findings that are included in the main body of the report text. The entire accident report (nine pages) can be viewed at the following link: (CAB Accident Report)

The CAB determined the probable cause to be:

"The Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot's unwise decision to embark on a flight which would necessitate flying solely by instruments when he was not properly certificated or qualified to do so. Contributing factors were serious deficiencies in the weather briefing, and the pilot's unfamiliarity with the instrument which determines the attitude of the aircraft."

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) did not issue formal recommendations as a result of this accident. However, the CAB did issue a Safety Message for Pilots regarding the differences in flight instruments highlighted by this accident, with an emphasis on the display differences between an artificial horizon and an attitude gyro. The Safety Message was included as an attachment to the CAB report and can be viewed at the following link: (Safety Message for Pilots).

Piloting and rating requirements

CAR 43 General Operational Rules

Operational requirements for Day/Night VFR/IFR

Night Flying

At the time of this accident, there were no FAA regulations in effect that addressed night flying except for recency of experience. It wasn’t until 1989 that FAR 91.507 restricted night VFR flying to an aircraft possessing the equipment for instrument flight and later that a commercial pilot without an instrument rating was restricted to 50 nm and could not fly at night. {CFR 61.133 (b) (1)}. This emphasizes the fact that night flying is very similar to instrument flying as even scattered clouds can block the natural horizon. With the advent of higher performance aircraft in the mid-1960s the accident rate for pilots flying into unanticipated weather conditions increased and resulted in the new regulations.

The pilot in this accident locked (caged) the confusing artificial horizon to a straight and level position to remove it from his scan. However, without a natural horizon the pilot was forced to fly with only the basic set of flight instruments, utilizing the turn and bank and pitot-static instruments to maintain control. This is a difficult task and as the accident report detailed, resulted in the pilot’s disorientation and loss of control.

CAR 60 Air Traffic Rules (Note: This is a link only to the relevant portions of CAR 60)

Airplane Instrumentation Requirements

The certification of the Beech Model 35 Bonanza predated the "modern" FAA aircraft design requirements, generally established in 1949. Relative to airplane instrumentation, the existing requirements specified how an airspeed indicator was to be marked, and that certain other instruments (airplane heading and engine-related information) must be supplied. An attitude indicator was not required, and therefore the means by which such an indicator would provide attitude information to the pilot was not explicitly defined. As the requirements developed, based on technological advances and service and accident experience, various advances in cockpit instrumentation would come under the umbrella of the newly developing regulations, but explicit requirements for attitude indicators were not developed until much later.

The accident flight was subject to certain schedule pressures, as the passengers were well known celebrities. As discussed in the accident report, Charles Hardin Holley (Buddy Holly), J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper), and Richard Valenzuela (Richie Valens) were traveling ahead of a group of performers in order to arrive in Moorhead, Minnesota in time to perform the following evening. Investigators identified weather conditions at the time of takeoff as deteriorating, and such that a requirement to fly solely with reference to instruments shortly after takeoff as being a "virtual certainty." Pressures to complete the flight due to the celebrity of the passengers, while not cited directly in the accident report, was considered a factor in the accident.

- Pilot's lack of proper certification, qualifications, and experience to fly in instrument meteorological conditions

- Serious deficiencies in the weather briefing

- Pilot's unfamiliarity with the primary pitch indicating instrument

- Visual meteorological conditions would exist for the entire flight

- The pilot's skill, experience, and qualifications were adequate for a night flight in poor weather conditions

- Weather briefings were adequate

- The primary pitch indicating instrument would not be confusing in instrument meteorological conditions

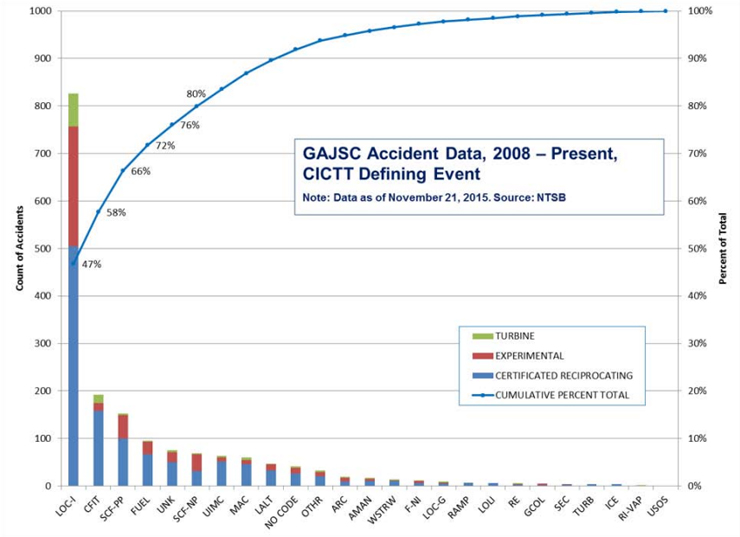

Loss of control in flight has been, and continues to be, a common accident cause in general aviation (GA). Loss of control accidents have occurred throughout aviation history. As an example, an FAA overview of the 2008-2015 fatal GA accidents showed that "Loss of Control" (LOC) was by far the major cause of accidents. Coupled with Controlled Flight into Terrain, it becomes apparent that these two factors are the primary causes of the majority of GA accidents. Rather than list precursor accidents, it is appropriate to identify the most significant historical and current GA accident causes.

The General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC) is a public-private partnership working to improve general aviation safety. The GAJSC Loss of Control (LOC) working group has identified safety enhancements that will result in lowering of the LOC accident rate. At this time, they include strategies focused on implementing safety technologies including:

- Angle of attack sensors and displays

- Simple autopilots and cockpit automation

- Novel displays enhancing pilot situational awareness to prevent LOC inflight (LOCi)

- Electronic parachute (emergency automatic landing)

- Flight trajectory management (advanced flight controls and fly-by-wire flight control systems for Part 23 airplanes)

- Improved flight envelope protection

- Airplane energy state awareness

In 1991, the FAA published Advisory Circular (AC) 60-22, Aeronautical Decision Making, which discusses risk and stress management tools, and how personal attitudes can affect and influence decision making relative to operational safety during flight and flight planning. The AC was published as a tool to help pilots recognize and alleviate unnecessary risk associated with flying activities. The AC, in two electronic documents, is available at the following links: (AC 60-22 part I) (AC 60-22 Part II).

Additionally, in 2003 and 2011, the FAA issued advisory material regarding attitude indicators and electronic instrument displays in airplanes certificated under 14 CFR Part 23.

Advisory Circular 91-75 Attitude Indicators provides guidance and justification relative to replacing the rate of turn indicator (turn and bank indicator) with a standby attitude indicator.

Advisory Circular 23.1311-1C Installation of Electronic Display in Part 23 Airplanes, provides guidance for the design, installation, integration, and approval of electronic flight displays in Part 23 airplanes.

Airplane Life Cycle

- Operational

Accident Threats:

- Unintended VFR to IMC

- Loss of Control

Operations:

- Business/Commercial

Accident Common Themes:

- Organizational Lapses

- Unintended Effects

Organizational Lapses

For approximately eight hours prior to the flight, the pilot repeatedly checked the weather in an attempt to stay up to date on local weather conditions and conditions along the planned route of flight. At each update, he was provided with information indicating that VFR conditions were persisting and would remain as such for the planned duration of the flight. At approximately 90 minutes and again at approximately 45 minutes prior to takeoff, the National Weather Service issued two flash weather advisories indicating that conditions had significantly deteriorated along the route of flight, to conditions worse than those required for VFR flight.

Investigators could find no evidence that either advisory was drawn to the attention of pilot, even though there had been opportunities as late as during taxi prior to takeoff. Investigators believed that if the pilot had been made aware of these advisories, he might have cancelled or delayed the flight until conditions improved.

Unintended Effects

Investigators cited the pilot's unfamiliarity with a new attitude indicator, which provided a pitch display opposite that of the artificial horizon to which he was accustomed, as a contributing factor to the accident. Almost immediately after takeoff, investigators believed that the pilot would have encountered instrument meteorological conditions and would have had to transition to reference to the attitude indicator for pitch information. Having very little experience with this attitude indicator installed on the accident airplane, investigators believed that he rapidly became confused by his pitch display and lost control of the airplane.

The following list is not exhaustive, but is indicative of the large number of accidents resulting from inadvertent flight from VFR into IMC conditions:

| List of inadvertent VFR into IMC accidents (accident number / aircraft model / location) | |

|---|---|

| ATL07FA029 Cessna 340A Charleston, SC | DEN03FA111 RV-6A La Junta, CO |

| CHI01FA093 Cessna 172 Centralia, IL | LAX02LA109 RV-4 Jacumba, CA |

| CHI05FA260 Piper PA-32-300 Wabash, IN | LAX03LA192 Argus Aviation CA-7 Angleton, TX |

| CHI06FA076 Cessna 421B Whelling, IL | NYC06LA136 Lancair 360 Montgomery, NY |

| CHI06FA232 Piper PA-23-250 Sault Ste Marie, MI | SEA03LA118 Herrin Hornet Newberg, OR |

| CHI08FA053 Beech V35B Springfield, IL | IAD02LA089 Puhl Genesis Petersburg, WV |

| DEN03FA068 Cessna 310D Provo, UT | CHI06LA164 Zenair Cricket MC-12 Lee's Summit, MO |

| CHI04FA255 Cirrus SR-22 Park Falls, WI | SEA08LA145 Lancair Legacy Murrieta, CA |

| DEN07FA059 Beech H-18 Great Bend, KS | ATL02LA099 Comp Air 7 Merritt Island, FL |

| DFW06FA021 Piper PA-34-220T Tomball, TX | DFW05LA102 - Spearman Raptor Bogalusa, LA |

| DFW07FA036 Cessna 310Q Waco, TX | CHI07LA113 Murphy Moose SR3500 Cotter, AR |

| FTW04FA045 Cessna 172 Grand Saline, TX | ATL04LA158 Pitts S-1 Durham, NC |

| LAX01LA303 Cessna P206B Willits, CA | CHI02LA176 BAR/Curtiss JN-4D Owatonna, MN |

| LAX02FA061 Cessna T337H Buena Park, CA | DEN07LA108 RV-6 Edgewater, CO |

| LAX04FA066 Cessna 421C Claremont, CA | DFW07FA023 Glasair Mineral Wells, TX |

| LAX05FA262 Piper PA-28-235 Big Bear City, CA | FTW04LA040 RV-6A Carthage, TX |

| LAX06FA089 Piper PA-30 Visalia, CA | LAX06LA170 RANS S-18 Stinger Llano, CA |

| MIA04FA047 Piper PA-23-160 Lake Worth, FL | MIA08FA141 Socata TBM700 Kennesaw, GA |

| MIA08FA091 AeroFab Lake LA-250 Skaneateles, NY | DFW08FA057 Piper PA-46-500TP San Antonio, TX |

| MIA08FA081 Cirrus SR22 Waxhaw, NC | ANC07FA073 Piper PA-46-350P Sitka, AK |

| NYC07FA100 Piper PA-23-250 Windham, CT | NYC07FA065 Socata TBM 700 Dartmouth, MA |

| NYC01FA109 BE 36 Middletown, RI | LAX07FA059 Piper PA-46-350P Concord, CA |

| SEA08FA013 Grumman American AA-5A Sequim, WA | ATL06FA044 Beech 200 Myrtle Beach, SC |

| DFW05LA118 Cessna 182 Little Rock, AR | LAX06FA071 LearJet 35A Truckee, CA |

| NYC03LA019 Mooney M20R Vineyard Haven, MA | DFW05FA170 Beech E90 New Roads, LA |

| NYC06FA145 Raytheon Acft B36TC North Garden, VA | IAD05FA047 Pilatus PC-12/45 Bellefonte, PA |

| NYC07FA159 Mooney M20F Brooks, KY | DCA05MA037 Cessna 560 Pueblo, CO |

| CHI02FA094 Piper / PA-31P Daleville, IN | NYC05FA042 Embraer EMB-110P1 Swanzey, NH |

| NYC06FA048 Beech D-55 Dawson, GA | DEN05FA051 Beech BE-90 Rawlins, WY |

| MIA01FA151 Mooney M20J Monroe, NC | SEA05FA025 Cessna 208B Bellevue, ID |

| CHI01FA235 Payne Giles G-202 Oshkosh, WI | IAD04FA021 Mitsubishi MU-2B-60 Ferndale, MD |

| CHI07LA150 Vans RV-7A Marysville, OH | LAX04FA165 Mitsubishi MU-2B-40 Napa, CA |

| CHI08FA224 Lancair Legacy Oshkosh, WI | NYC03FA080 Dassault Aviation DA-20 Swanton, OH |

| LAX04LA106 Thorpe T-18 Compton, CA | DEN04MA015 Cessna 208B Cody, WY |

| NYC08LA001 Varieze Chesapeake, VA | IAD03FA043 Beechcraft B200 Leominster, MA |

| SEA03FA041 KIS TRI-R TR-1 Puyallup, WA | DEN03FA045 Piper PA-46-500TP Albuquerque, NM |

| ATL05LA078 Earnest Jodel D-9 Memphis, TN | IAD03FA035 Socata TBM 700 Leesburg, VA |

| CHI01FA244 Hamilton SH3 Oshkosh, WI | FTW03FA036 Israel Aircraft Industries 1124A Taos, NM |

| DFW07LA090 RV-6 Sinton, TX | DCA03MA008 Beech King Air 100 Eveleth, MN |

| IAD02LA028 Wilburn Jodel F-12 Clarksville, VA | DEN01FA113 Mitsubishi MU-2B-20 Cerrillos, NM |

| MIA03LA045 Bornhofen Twinjet 1500 Melbourne, FL | DEN01FA094 Cessna 208B Steamboat Springs, CO |

| ATL04LA001 Hornet Saint Marys, GA | NYC06LA160 Aerial Productions Intl. Inc. Acrojet Special |

| FTW03FA054 Cessna 402C Lewisville, TX | MIA06LA106 Piper PA-23-250 Caribbean |

| FTW02LA086 Air Tractor AT-502B Extension, LA | SEA07FA012 Cessna 172M Escalante, UT |

| ATL06LA110 Vans RV-6 Hartselle, AL | CEN09LA512 Hooper Mustang MMII Gladwin, MI |

| ATL02FA160 Beech BE-55 Jacksboro, TN | LAX05LA283 Avions Robin R.2160 Avalon, CA |

| LAX04FA177 Piper PA-32R-301T Ukiah, CA | NYC08FA319 Piper PA-32 Atlanta, GA |

| CEN10FA028 Beech 100 Benavides, TX | CHI07LA238 Swanson Aventura II Lakewood, WI |

| LAX06FA289 Piper PA-23-160 Sana Maria, CA | CHI01FA100 Piper PA28-180 Earhard, MN |

| DEN05FA074 Cessna T210G Ouray, CO | CHI01LA294 Piper PA-18-150 Alice, ND |

| LAX01LA281 Lancair 360 Placerville, CA | DFW08FA040 Cessna 172 Marlow, OK |

| CHI03LA074 North American P-51D Urbana, IN | ANC06LA030 MOONEY M10 SALINAS, CA |

| LAX08FA068 Mooney M20C Riverside, CA | LAX01LA141 Vans RV-6A Baker, CA |

| CEN09FA178 Cessna 182M Albany, LA | ATL05FA086 Piper PA-18-135 Conway, SC |

| CHI03LA216 Cessna 172H Isle, MN | WPR09FA112 Beech A36 Avalon, CA |

| DFW05LA012 Huber DR 107 Fletcher, OK | LAX04FA207 Piper PA-44-180 Wittmann, AZ |

| MIA03FA077 Aeronca Champion 7BCM Pahokee, FL | DFW05FA145 Beech 95-B55 Jeanerette, LA |

| ERA09LA043 Vans RV-6 Martinsville, VA | CHI02LA166 Jacobs Rutan Vari Viggen Urbana, IL |

| SEA07GA142 Christen Industries A-1 Loa, UT | MIA04FA128 Cessna R182 Milton, FL |

| ERA10LA158 Rans S-6S Mayaguez, PR | LAX08FA256 Cessna 172K Gearhart, OR |

| CHI02FA215 Piper PA-30 Marble Hill, MO | CHI01FA298 Vans RV-6 Grayslake, IL |

| LAX08LA078 Vans RV-7A Winslow, AZ | ATL03FA136 Beech BE-55 Winder, GA |

| DEN06FA065 Cessna 310 Heber City, UT | NYC05FA006 Beech H50 Hartwood, VA |

| LAX08LA191 Cessna 172S Oceanside, CA | ATL04FA038 Beech 55 Griffin, GA |

| NYC05FA006 Beech H50 Hartwood, VA | CHI08FA045 Cessna 208 Columbus, OH |

| CEN09LA331 Gentry John K Chinook PL Bridgeport, TX | CHI03FA088 Cessna 182 North English, IA |

| CHI03LA117 Rans S-7 Baudette, MN | SEA07FA119 Cessna 182 Marion, MT |

| SEA07FA199 Cessna 182 New River, AZ | ERA09LA454 John M Nieuport 1 Brasstown, NC |

| LAX04FA168 Alon A2 Cameron Park, CA | ERA09FA053 Cirrus SR22 Tallahassee, FL |

| DEN07FA165 Cessna T210 Moriarty, NM | DEN01FA056 Beech V35B Green River, UT |

| DFW06FA140 Aviat A-1B Edna, TX | LAX04FA226 Piper PA-28R-180 Columbia, CA |

| ERA09LA019 Hargett Sky Ranger II Rock Hill, SC | LAX07FA123 Cessna 172 Page, AZ |

| IAD05LA083 Titan Tornado Bath, PA | DFW08FA212 Piper PA-24-250 Yuma, CO |

| SEA02GA053 Piper PA-31 Atlanta, ID | NYC02FA200 Mooney M20E West Creek, NJ |

| DEN08FA152 Gulfstr. Am. Corp AA-5A Baxter Pass, CO | CHI07FA182 North American Navion Colona, IL |

| MIA02FA113 Piper PA-46-310P Naples, FL | CHI07FA032 Cessna 172 Crookston, MN |

| MIA08LA002 Bellanca 7GCAA Toughkenamon, PA | SEA05FA201 Cessna P210 Salmon, ID |

| CHI08FA150 Socata TBM 700 Iowa City, IA | NYC04FA144 Cessna P210 Dunkirk, NY |

| CHI08FA133 Beech V35 Bristol, OH | NYC05FA001 Cessna 172 Germantown, NY |

| DEN03FA157 Beech 35 Belen, NM | DEN01FA044 Aero Vodochody L-39 Watkins, CO |

| ERA09FA169 Cirrus SR20 Deltona, FL | CHI06LA070 Cessna 172 Harrison, MI |

| ANC01FA084 Maule M-5-235C Bettles, AK | ANC06FA080 Piper PA-12 Cooper Landing, AK |

| MIA03LA146 Sonerai Sonerai IIB Lakeland, FL | CEN09FA369 Cessna 182 Dougherty, TX |

| SEA02FA171 Cessna 175 Arlington, WA | MIA07LA091 SNS-2 Guppy Stewartstown, PA |

| NYC05FA058 Grumman American AA-5 | NYC02FA196 Piper PA-30 Gilford, NH |

| DEN06FA132 Beech 35 Telluride, CO | MIA02FA032 Cessna 152 Poplarville, MS |

| DEN06FA065 Cessna 310 Heber City, UT | LAX02FA191 Piper PA-23-160 Rio Rico, AZ |

Technical Related Lessons

Flight using visual flight rules (VFR) requires a continuous awareness of the horizon. Pilot loss of an external horizon reference, for even a few seconds, can often result in sensory illusions and correspondingly incorrect control inputs. This can rapidly lead to aircraft attitudes from which recovery is difficult or impossible. (Threat Category: Unintended VFR to IMC)

- The pilot in this accident was not qualified to fly with sole reference to airplane instruments. The flight was predicated on weather forecasts that indicated conditions conducive to VFR flight. In fact, weather conditions deteriorated prior to the flight, and associated weather briefings to the pilot did not present a complete picture of the actual conditions. Investigators believed that shortly after takeoff, the pilot encountered conditions that would have required flight with reference to instruments only, for which he was not qualified, and quickly lost control of the airplane, resulting in the accident.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Primary attitude flight displays should not be ambiguous or inconsistent relative to the three-dimensional external environment (up, down, left, right). Lack of familiarity with specific flight instruments intended to allow flight in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) can lead to confusion and, potentially, to incorrect control inputs and/or loss of control. (Common Theme: Unintended Effects)

- The Sperry F3 gyro horizon, as installed on the accident airplane, was a new design for an artificial horizon, including a feature in which the pitch display was reversed relative to a conventional artificial horizon. The face of the instrument was well marked and used different colors to depict the sky and ground, which would aid in differentiating up or down pitch indications but was considered by investigators to be potentially confusing.

Pitch indication convention had been that when climbing, the pitch bar is in the upper half of the instrument, above the indicated horizon. For descents or dives, the pitch bar is below the horizon. The Sperry F3, for a climb, would show a pitch bar below the instrument horizon, and display the opposite for a dive. Investigators concluded that for a pilot not qualified to fly solely with reference to instruments, who was also unfamiliar with the Sperry F3, inadvertent flight into IMC conditions, and transition to reference to the unfamiliar indicator, could have been confusing and lead the pilot to make pitch inputs opposite to those that were actually required to maintain level flight.

- On the accident flight, investigators determined that the pilot flew into IMC conditions almost immediately after takeoff, and though he intended to remain VFR, would have been required to transition to flight by reference to airplane instruments for which he was not qualified. Investigators further stated that the pilot was unfamiliar with the Sperry F3 and could have become confused by its reversed pitch sensing, causing him to make incorrect pitch control inputs and lose control of the airplane.

Comprehensive, complete, and current weather briefings, especially in cases of marginal or deteriorating conditions, are essential to the safe conduct of a flight. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapse)

- Beginning as early as 1730 the afternoon prior to the flight, the pilot began checking weather forecasts and current conditions at the Air Traffic Communications Service (ATCS) at Mason City airport. He received multiple weather briefings over the hours prior to the flight, including a final briefing during taxi just before takeoff. At each briefing, he was supplied with weather information indicating that VFR conditions were present and would continue to exist for the planned duration of the flight and over the planned flight route.

However, at 2335, a flash weather advisory was issued by the U. S. Weather Bureau in Minneapolis, and at 0015, another was issued by Kansas City, both indicating rapidly deteriorating conditions, including visibility less than that required for VFR flight, and the presence of snow and inflight icing. The ATCS communicator did not provide this information to the pilot, who was therefore unaware of the changed weather conditions.

Investigators stated that the ATCS communicators had the responsibility to provide all available weather information, and to interpret that information, if requested. Investigators concluded that the preflight weather briefings had been inadequate, and were a contributing factor to the accident, in that, had the pilot been made aware of the changed conditions, he might have cancelled or delayed the flight until improved weather conditions existed.