Bombardier DHC-8-400

Photo copyright Eric Trum - used with permission

Colgan Air Flight 3407, N200WQ

Clarence Center, New York

February 12, 2009

On February 12, 2009, Colgan Air, a regional air carrier, was operating a Bombardier DHC-8-400 turboprop (Q-400) as Continental Connection 3407 from Newark, New Jersey to Buffalo, New York. The aircraft experienced an aerodynamic stall on a straight-in, night instrument approach and impacted a house five miles from the Buffalo-Niagara Airport.

As the aircraft approached Buffalo, New York, the plane was initially travelling too high and too fast, requiring deceleration in order to intercept the Instrument Landing System (ILS) and glideslope. In order to slow down the aircraft to meet the outer marker, the flight crew lowered the landing gear, applied drag, and reduced thrust, causing the aircraft to continue to decelerate. As a result of continuing airspeed decay, the stick shaker and stick pusher activated. The captain did not increase airspeed and did not respond correctly to the stall warnings, overriding them both. Instead, he applied incorrect control input by pulling the yoke full aft, placing the aircraft into a full aerodynamic wing stall from which recovery was impossible. The ground impact killed the two pilots, an off-duty pilot, two flight attendants, and 44 passengers onboard, as well as one person on the ground.

Photo copyright Gary Wiepert@Reuters - used with permission

History of Flight

Colgan Air Flight 3407, a 74-seat turboprop Q-400, taxied out of the Liberty International Airport at Newark, New Jersey, bound for the Buffalo-Niagara Airport in New York. It was a 14 CFR part 121 passenger flight scheduled to depart at 1910 EST. However, the aircraft incurred a two-hour delay on the ground and took off at 2118 EST.

Colgan's flight time to Buffalo was estimated to be 53 minutes. The departure airport weather consisted of light snow and fog with a wind of 15 knots. Onboard were two pilots, two flight attendants, an off-duty Colgan captain, and 44 passengers. The pilot-in-command was new to the Q-400, having flown it for two months with a total of 109 hours in the airplane.

Investigators determined that the pilots violated the Sterile Cockpit Rule, as the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) revealed the first officer used her cell phone during taxi to send a text. Additionally, throughout the long taxi and during much of the flight, the pilots engaged in almost continuous conversation about personal subjects. It was believed by investigators that these distractions were the reason the pilots delayed checklist completion, forgot to use certain techniques for icing conditions, and failed to notice the plane was slowing and approaching a stall.

During the inflight portion of the flight, the voice recorder picked up yawns from both the captain and the first officer. In addition, the first officer told the captain that she did not feel well.

The Buffalo weather was a few clouds at 1,100 feet above ground level (AGL) with a ceiling of broken clouds at 2,100 feet AGL and overcast clouds at 2,700 feet AGL. Visibility was three statute miles in light snow and mist. The temperature was 1º C with the dew point -1º C. The winds were from 240 degrees at 15 knots, gusting to 22 knots. Night visual meteorological conditions prevailed, and the flight crew was planning for an instrument approach to runway 23 at the Buffalo airport.

Eleven minutes after takeoff, the plane was climbing to 16,000 feet when the flight crew turned on the propeller anti-ice system and the airframe and engine de-icing system. They also correctly put the Ref Speeds Switch to INCREASE (ON), which raised the low-speed cue on their airspeed indicator. Ice had formed on both windshields, which they discussed. Since the first officer had a good view of the leading edge of the right wing, she reported to air traffic control that they had light-to-moderate rime ice.

View Larger

FAA regulations for 14 CFR Part 121 operations during a high-workload, critical phase of flight, informally known as the Sterile Cockpit Rule, specifically prohibits a flight crew member from performing non-essential duties or activities (e.g. personal conversation, eating, etc.) when the aircraft is taxiing, taking off, landing, and during all other operations below 10,000 feet. However, investigators noted that the CVR transcript recoded that the crew continuously engaged in personal conversations throughout the flight.

Investigators determined that, "Because of their conversation, the flight crewmembers squandered time and their attention, which were limited resources that they should have used for attending to operational tasks, monitoring, maintaining situational awareness, managing possible threats and preventing potential errors."

In preparation for the approach, the first officer incorrectly determined a non-icing approach speed. Since the Reference Speeds Switch was in the INCREASE position, the stick-shaker stall warning would activate 13 knots above the approach speed they had set.

As the pilots followed Buffalo air traffic control's headings for their approach to landing, they were at 2,300 feet above mean sea level (MSL) or 1,500 feet AGL in light snow and mist with three miles visibility. The controller informed the crew that they were three miles outside of the outer marker and cleared them for the ILS runway 23 approach. The aircraft was travelling at 184 knots, 50 knots too fast for their position in the approach. Therefore, to slow rapidly, the captain called for flaps to five degrees, reduced power, called for landing gear down and propellers to maximum RPM. The airspeed decreased 50 knots in 21 seconds.

Investigators noted that the captain, due to his failure to monitor safe airspeed, missed the rising low-speed cue during his instrument scan, as well as the high pitch attitude; and, the first officer did not detect the captain's error.

After the captain called for flaps 15 degrees, the shaker activated at 131 knots as the flaps were extending. The autopilot disconnected, by design. However, post-flight examination determined the airplane was not in a stalled condition, as the flight data recorder showed the angle of attack to be only eight degrees and 20 knots away from the actual stall speed of 111 knots.

The captain incorrectly pulled the nose up to 18 degrees with the force of 1.4 Gs, and the airplane entered a full stall condition. With a mismatch between the Ref Speeds Switch and the flight crews approach speed, and no reminder on the approach checklist to double-check the position of the switch, investigators felt the captain's improper inputs were consistent with startle and confusion, and that his history of training failures may have played a role.

View: Colgan Checklist

As airspeed continued to slow inside the low-speed band, the cockpit became noisy as the stick shaker clacked and the autopilot disconnect horn continued to sound for the remainder of the flight. Despite the captain adding partial power, the airspeed further slowed inside the low-speed band due to the captain's increasing back pressure on the yoke.

According to Colgan's procedure for approach-to-stall, the pilot flying was required to call, "Stall," advance the power levers and call, "Check Power." According to CVR data, the first officer, as pilot monitoring, did not call "Stall" when the captain missed this step. She did not report that the power levers were not fully advanced, nor did she advance the power levers herself.

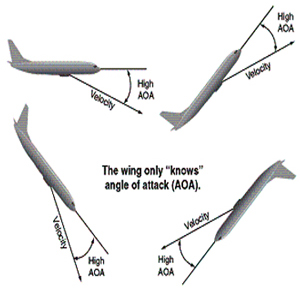

As the airplane encountered steep roll reversals, the stick pusher, a stall recovery device, triggered at 100 knots and 18 degrees angle of attack to forcefully lower the nose; yet, the captain continued to fight the pusher by pulling back on the yoke.

Without direction, the first officer raised the flaps from 15 degrees to zero, thus dumping whatever lift the flaps were providing. While this was a mistake in procedure, investigators concluded it had minimal effect upon the ultimate outcome.

As the aircraft continued to bank left and right, the pusher activated a second time. In response, the captain applied a 90-pound pull force, which temporarily disconnected the device that could have recovered the aircraft from the stall. The first officer asked if she should put the gear up and the captain agreed.

With the airplane in a right bank, the pusher fired for the third time and stayed on for the remainder of the flight. The captain continued to pull the yoke to a final angle of attack of 13 degrees beyond the stalling angle, and the nose fell through the horizon to 50 degrees down and the aircraft impacted the ground. The time elapsed from the stick shaker until impact was 27 seconds. All passengers, crew, and a person on the ground were killed.

NTSB photo of Colgan accident site (right)

View Larger

Approach Management Considerations

All operators have standard operating procedures (SOPs) for their pilots to follow during the approach phase of flight. These SOPs address when and how pilots should configure the airplane and prepare for the approach to the airport.

During the approach phase of flight, the pilots determine, set and confirm the correct approach airspeed. For normal approach speeds, all operators begin with Vref speed, which is 1.3 times the landing stall speed and is a fixed number determined during aircraft certification. Operators usually add ten knots to Vref speed (Colgan added seven) to obtain the normal approach speed.

Both pilots then place that approach speed on their respective airspeed indicator by setting a marker, called a “bug.” If they are going to fly a non-standard approach, such as one with gusty winds, in icing conditions, or landing with a non-normal flap setting, they must add additional speed to their normal approach speed and then set the new bug.

Also during the approach phase, while air traffic control is vectoring the airplane (giving headings) to intercept the approach course, the pilots have slowed and configured the airplane for the approach. This means they have extended approach flaps, slowed to a speed appropriate for those flaps, and are at the proper intercept altitude. As they join the approach course, they should begin their descent by lowering the gear, selecting flaps to the landing setting and slowing slightly to their final approach speed. This puts the aircraft on a stabilized approach - a constant angle glidepath to the runway at a constant airspeed and configuration.

While the pilots slow and configure the aircraft, the Pilot Flying (PF) is responsible for controlling the aircraft, even if it is on autopilot. The Pilot Monitoring (PM) is at all times responsible for observing the aircraft’s flight path and energy state. If there are any deviations, the PM is to tell the PF and intervene, if necessary.

Stall Identification and Protection

What is a Stall?

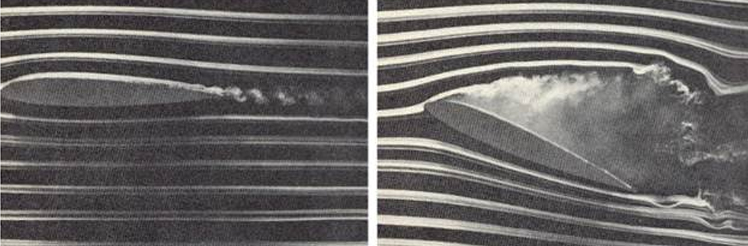

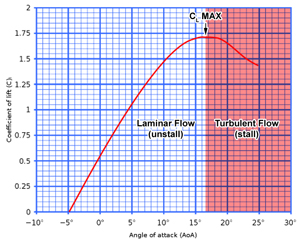

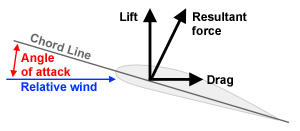

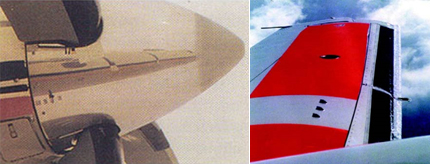

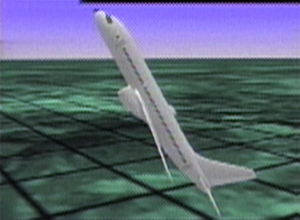

A stall is the rapid transition from laminar flow to separated, turbulent flow on the upper surface of the wing, substantially reducing the airfoil's lift generation. The stall from the Colgan accident occurred because the pilot reacted incorrectly to a stall warning and overpowered the stick pusher by pulling the yoke aft, forcing the nose of the aircraft up and increasing the angle of attack until lift was lost and a stall occurred. Prior to a stall, the wing's airfoil experiences laminar airflow (see left photo). However, at high angles of attack, the airflow becomes turbulent and separates, thereby substantially reducing lift (see right photo). In order to reestablish lift, it is essential that the pilot reduce the angle of attack thus restoring laminar flow on the wing surface. The standard way to decrease the angle of attack is to use the elevator to pitch the nose down, as the elevator controls pitch in all flight conditions.

The following video shows a normal wing inflight and a wing in a stall:

View Larger

The "wind" referred to in this graphic is the relative wind, the wind the plane makes by moving forward. The chord line is an imaginary line from the leading edge to the trailing edge of the airfoil. The angle of attack is the angle between the chord line and the relative wind, and lift is always perpendicular to the relative wind.

Effect of Ice on the Stall

View Larger

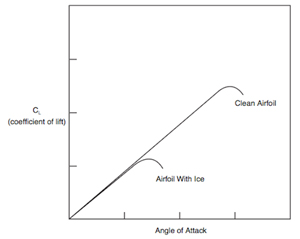

Ice accumulation negatively affects the stalling angle of attack and causes the stall to occur at a lower angle of attack (faster airspeed) as shown in the graph.

As a result of the ice accumulation, a faster approach speed is needed in icing conditions since the approach speed increase is about the same as the increase in the stall speed. The increased stall speed is due to the roughness of the ice, which creates a turbulent airflow over the wing, thus reducing lift. The plane may stall before the stick shaker activates and can cause pitch and roll excursions during the stall. For some airfoils, even small amounts of ice (equivalent to medium grit sandpaper) can increase the stalling speed.

Based on the Colgan flight crew's discussions learned through CVR analysis, investigators believed the aircraft was accumulating rime ice. Rime ice is rough and opaque on the leading edge of the wing and forms when super-cooled water drops rapidly freeze on impact. However, investigators determined that icing was not a cause of the accident.

Stall Recovery Training

At the time of the accident, the FAA used Practical Test Standards (PTS) to establish the criteria for successful completion of an approach-to-stall recovery procedure. Reducing the angle of attack in an approach-to-stall was not the procedure for transport pilots, and there was no published procedure to recover from a full stall in a transport airplane. Until 2012, when the FAA changed the stall recovery techniques, the approach-to-stall recovery procedure was to add maximum power and maintain altitude within 100 feet.

The mistaken practice of adding power to recover from an impending stall began when the aviation industry first introduced transport aircraft. Since there were no simulators, pilots had to train while in flight. Transport airplanes could lose significant altitude in a stall and severe structural stresses from the stall could cause damage to the airframe and engines. Thus, stall training was not conducted in actual flight conditions.

As a result, early transport pilots developed a technique to slow the aircraft to the first indication of a stall and then added power to speed up. This maneuver was known as an "approach-to-stall;" however, the airplane was not in a stall. The expectation was that pilots would be able to recognize the early indication of a stall and recover, thus never getting the aircraft into an actual full aerodynamic stall.

Photo copyright Ethan Arnold - used with permission

When flight simulation devices (FSTDs or simulators) entered flight training, they were not able to replicate what the airplane would do in an actual stall. Therefore, pilots continued to practice only approach to stalls.

Following the Colgan accident, Congress required the FAA to ensure that transport pilots train in realistic full-stall recoveries in a simulator that accurately represents the airplane in the post-stall regime. The FAA eliminated recoveries that emphasized immediate application of power and zero or minimal altitude loss. Instead, pilots must now demonstrate they reduce the angle of attack as the first step in recovery from an impending or full stall and use power only after the wings are again generating lift and the plane is again flying. However, this results in a loss of altitude.

View: Approach-to-stall procedure, PTS in effect at the time of the accident (July 2008)

View Larger

At the time of the Colgan accident, it was the FAA's PTS that established the criteria for successful completion of the Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP) and Aircraft Type Rating. Adherence to the provisions of the PTS was mandatory. The PTS stall recovery procedure was to add maximum power with minimal loss of altitude. Most flight examiners expected the pilot to lose no more than 100 feet.

The company's approach- to-stall profiles were consistent with the FAA's ATP PTS. At the time, there was no training requirement to expose flight crews to the activation of the stick pusher. Some Colgan flight instructors showed the pusher activation to their students; however, investigators could not determine if the captain had seen a demonstration.

In the aftermath of the Colgan accident, the FAA changed the stall recovery procedure and replaced the PTS with the Airman Certification Standards (ACS). The new stall recovery training emphasizes that reducing the angle of attack is the first pilot action in recovering from an impending or full stall. The pilot uses power only after the wing has reestablished laminar flow on the upper surface, is generating lift, and is again "flying" and uses only as much pitch as is needed to stop the altitude loss. The altitude loss that occurs depends upon the severity of the stall and the amount of pitch down that occurs so that a predetermined altitude loss is not possible. For the complete training template, see Relevant Regulations / Policy / Background.

Flight crew Performance

Pilot Experience of the Accident Aircraft

Captain's background - Colgan did not learn of the accident captain's previous experience at other air carriers nor his training failures at those carriers before they hired him. Investigators discovered that the captain, age 47, had a flawed performance history from the beginning of his aviation training. In 1991, he failed his initial instrument rating when he had 125 hours of flying time. In 2002, he failed his initial commercial single-engine land certificate at 296 hours. Two years later, he failed his initial multi-engine rating and had to repeat the entire flight portion.

In August 2004, Gulfstream Flight Academy in Orlando, Florida accepted him into their first officer program. The company had designed their curriculum for low-time pilots who wanted to gain flight hours in an airline environment. Gulfstream provided advanced training in a two-pilot regional turboprop airliner, a Beechcraft 1900, which took 6-8 months and resulted in a type rating in the airplane. The captain flew as first officer for Gulfstream International Airlines (GAI) throughout Florida and the Bahamas for five months, accumulating 250 hours.

Photo copyright Sebastian Elijasz - used with permission

Investigators determined that the captain had difficulties with aircraft control and basic attitude flying, and that Gulfstream's program focused on systems and operation of the Beech 1900 and did not concentrate on instrument flying since pilots should have already learned that basic skill. In September 2005, Colgan Air hired him as a first officer on the Saab 340. At that time, Colgan's minimum hiring requirements were 600 total flight hours and 100 multiengine hours. The captain met these requirements as he had 618 hours total time, 290 of which he had accumulated as a first officer in the Beech 1900 at GIA.

At that time, the Pilot Records Improvement Act (PRIA) of 1996 did not require an FAA background records check for pilots. Investigators determined that Colgan asked if the captain had ever failed a check ride to which he admitted only one failure on his instrument rating but did not provide further details of other failures. On his first proficiency check at Colgan in the Saab, his record showed that he received a "train to proficiency" grade, meaning he needed extra periods in which to bring him up to standards.

His next flight check, the recurrent check as a Saab first officer, was noted as unsatisfactory in the areas of rejected takeoffs, general judgment, landings from a circling approach, non-precision approaches and the oral exam. After retraining, he passed the check the next month.

Investigators learned that the captain failed his initial first officer flight check for his airline transport certificate on the Saab. Despite the fact that he had demonstrated problems with three check rides during his employment with Colgan Air, the airline did not have a formal program for weak pilots. During his checkout as captain in the Saab, he completed all maneuvers without any repeats or failures; however, performance records noted that he was rough on the controls. At the time of the accident, he was still a new captain in the Q-400, having flown it only two months with 109 hours in the airplane, and reportedly relied heavily on the autopilot for aircraft control. Prior to the accident, a records review indicated the captain experienced three training failures at Colgan that included two training sessions and one checkride. He was allowed to be re-evaluated and passed subsequent training.

First officer's background - The first officer was 24 years old and held a commercial pilot certificate with second-in-command privileges on the Q-400 and a first-class medical with no limitations. She worked as a light airplane flight instructor in Scottsdale and Phoenix, Arizona, accumulating 1,470 hours of light airplane time. At the time of the accident, the first officer had 774 hours in turbine airplanes, bringing her total flying time to 2,244 hours. FAA records indicated no accident or incident history nor enforcement action.

Pilot Fatigue Program at Colgan

Colgan's fatigue policy for its crewmembers, found in their Flight Operations Policies and Procedures manual, was addressed during indoctrination training. Prior to the accident, crew members who were unable to complete assignment because of fatigue were required to notify systems operations and complete the required fatigue form within 24 hours of being released from duty. However, from 2008 until the beginning of 2009, only a dozen pilots had called in "fatigued." At the time of the accident, Colgan did not provide any information to its pilots regarding fatigue prevention.

Crewmember Activities

Captain's activities - This was the captain's third duty day. Investigators could find no information as to where he slept the night prior to the accident. However, he accessed the company computer that night at 2151, 0300, and 0730, so it was apparent he was awake during these times. The NTSB thought he might have been fatigued during the flight to Buffalo.

First officer's activities - The day before the accident, the first officer commuted from her home in Seattle to Memphis to Newark, arriving the day of the accident at 0630 eastern time. She slept on the airplane and then in the crew room. Colgan's policy did not permit pilots to use the crew room for rest; however, investigators determined it was a common practice at Colgan.

Investigators believed the pilots' performance may have been impaired because of fatigue, but the extent to which it contributed to their performance deficiencies could not be conclusively determined.

Flight in Icing Conditions

Q-400 Ice Protection System

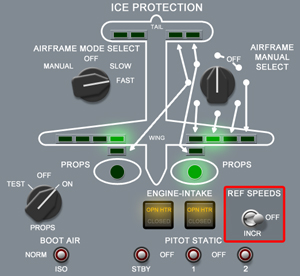

The FAA approved the Q-400 for flight in icing conditions. It has an ice detection system, an anti-icing system (which prevents ice buildup) and a de-icing system (for ice removal). Investigators concluded that the aircraft had minimal aircraft performance degradation from ice accumulation, so the icing conditions they were in did not affect the flight crew's ability to fly and control the airplane. However, it was concluded that their mismanagement of one of the components of the plane's ice protection system did affect the crew's activity in responding to the low-speed condition. When this system senses icing, the pilots are required to activate the propeller heaters and the airframe de-icing system and then select the Ref Speeds Switch to INCREASE (ON). The INCREASE position causes the stall protection system to indicate additional approach speed targets. When the airplane is clear of ice accumulation and out of icing conditions, pilots turn the anti- and de-icing systems to OFF and the Ref Speeds Switch to OFF.

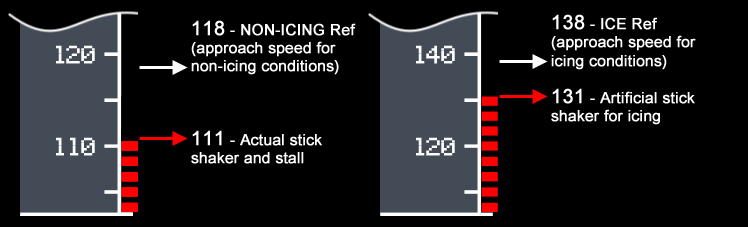

Turning the Ref Speeds Switch to the INCREASE position physically moves the top of the airspeed red and black band (low-speed cue) 15 to 20 knots faster, depending on the planned landing flaps (15 knots faster for a flaps 35 landing and 20 knots faster for a flaps 15 landing). The flight crew had planned for a flaps 15 landing, thereby requiring a 20-knot increase in reference speed.

Two ice detection probes are on each side of the airplane's nose, powered automatically by aircraft electrical power. With the Ref Speeds Switch set to INCREASE (as it was for the accident airplane), when one or both probes detect more than .5 millimeters of ice, they first flash an ICE DETECTED light on the center panel in black letters on white. This message changes in five seconds to white letters on a black background.

However, with the Ref Speeds Switch set to OFF, upon detecting ice, the ICE DETECTED light flashes yellow until the pilot turns the Ref Speeds Switch to INCREASE. The ICE DETECTED message also appears periodically during icing conditions, for at least a minute each time.

As soon as the pilot places the Ref Speeds Switch to the INCREASE position, [INCR REF SPEED] appears constantly in white on the center panel. Thus, the Colgan pilots had a continuous reminder to increase their approach speed, which investigators determined that they did not accomplish.

Reference (Ref) Speeds Switch

With the Ref Speeds Switch set to INCREASE, as the airspeed slows to the top of the red low-speed band, it has reached a bias or "padded" speed, which that day added 20 knots for the icing conditions. The Q-400 airplane exhibits all the normal stall indications, stick shaker and autopilot disconnect. However, this is an artificial stall indication, and the airplane is not actually in a stall. In addition to the Ref Speeds Switch, the low-speed cue can also change its position in response to flap setting, engine power, and Mach number.

On the accident flight (Ref Speeds Switch set to INCREASE,), the top of the low-speed cue (and artificial stall indications) was 131 knots. Their final approach ref speed (Ref + 7) should have been 138 knots.

View Larger

When the airplane is out of icing conditions, the pilot turns the Ref Speeds Switch to OFF. The top of the red band then physically moves 20 knots to a slower position. The top of this slower low-speed cue now displays the actual speed at which the airplane will stall, since there is no airspeed "padding" for icing. On the accident flight, the non-icing (actual) stall speed would have been 111 knots and the non-icing final approach speed would have been 118 knots.

The first officer incorrectly gave the captain a non-icing approach speed of 118 knots. With this incorrect speed, the stick shaker would activate, and the autopilot would disconnect when the artificial low-speed cue was reached at 131 knots as they slowed. However, they were not actually stalling at that point.

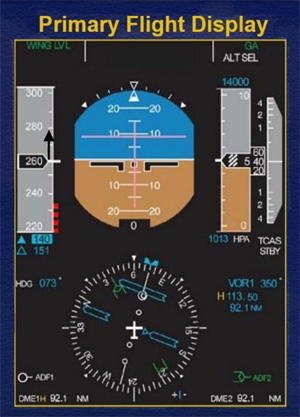

Low Speed Alerting

The Q-400's Low-Speed Cue is a red and black vertical band that extends from the left side of the Primary Flight Display (PFD). Slowing to the top of this band informs the pilots of a critically slow airspeed for the airplane's configuration or its operating condition (such as ice). At the top of the band the stick shaker activates, the autopilot disconnects, and the airspeed numbers and its window change from white to red.

Conclusion

The Colgan Air accident is an example of a loss of control in-flight (LOC-I), which is the leading cause of fatal accidents in the United States and in commercial aviation worldwide. In both air carrier and general aviation operations, loss of control frequently begins with an aerodynamic stall followed by incorrect recovery procedures. Investigators learned that the pilot flying failed to monitor airspeed, disregarded stall warning alerts, and allowed the aircraft to slow below its stall speed while keeping the yoke full aft, physically defeating the stick pusher's attempt to lower the nose.

While the accident occurred in icing conditions, the NTSB determined that icing was not a factor in the accident. Instead, investigators concluded that shortcomings in pilot training for stalls, deficiencies in flight crew member screening prior to employment, and lapses in professionalism were major issues in the Colgan accident. Additionally, air carrier and FAA oversight were found to be inadequate.

Following this accident, the FAA and industry implemented numerous safety and operational improvement initiatives, including:

- Expanded training - full stall, enhanced simulators, additional training requirements

- Pilot Record Database - records tracking database and information sharing

- Fatigue policies and practices - duty time definition and dissemination of information

- Safety oversight - flight crew qualification, safety management systems

Colgan Flight 3407 Memorials

Photo of stone near Long Street Memorial - Copyright Jerry Hanley - used with permission (right)

Long Street Flight 3407 Memorial

Located at the site of the home on Long Street where the airplane crashed is the Flight 3407 Memorial, dedicated June 2012. The walkway is in the shape of an airplane wing that is as long as the accident airplane. Embedded in the walkway are paving stones for each of the 51 people killed.

Patriots and Hero's Park, Williamsville, New York

This memorial outside of Buffalo was commissioned by Russell Salvatore. It is a memorial of the rising Phoenix, designed by Don Parrino, as a gift to the people of Buffalo.

Forest Lawn Memorial, Buffalo, New York

Colgan Air commissioned this memorial in the Buffalo Forest Lawn Cemetery. Within the crypt are remains of the victims.

Clarence Public Library, Clarence, New York

The Flight 3407 Civic Memorial, located in the Clarence library, was created by the Remember Flight 3407 Inc.'s Board of Directors, with the assistance of Hadley Exhibits and Erie County historian C. Douglas Kohler.

Flight 3407 Memorial 5K Race, Clarence Town Place Park

This yearly 5K race in October honors those lost in the Colgan accident and uses event proceeds to fund the building and maintenance of the Clarence Library memorial and local charities.

The NTSB compiled 46 findings for the Colgan accident. These findings included concerns primarily in the following areas:

- Captain's failure to effectively manage the flight

- Breakdown of sterile cockpit discipline

- Captain's weakness in aircraft control

- Colgan lack of remedial training

- Inadequate full stall training

- Inadequate FAA oversight

- Colgan unaware of captain's previous checkride failures

- Pilot fatigue likely

- Ambiguous low airspeed alerting systems

View: NTSB Complete List of Findings

View: Colgan Accident Report

The NTSB made numerous recommendations as a result of the Colgan accident that included concerns primarily in the following areas:

- Leadership and professionalism training

- Pre-employment training records

- Full stall and stick pusher training

- Monitoring skills training

- Ref Speeds Switch procedures

- Airspeed Indicator Display and low-speed alerting system

- Simulator fidelity to support full stall training

- Utilization of Flight Operational Quality Assurance (FOQA) programs

- Sterile cockpit procedures

- Fatigue risks

View NTSB List of New Recommendations

View NTSB List of Reiterated Recommendations

View NTSB List of Previously Issued Recommendations

Airplane Stall Certification Requirements

During the certification process of any transport airplane, flight test pilots perform stalls many times for several reasons. They measure stall speeds (VS1G) throughout the weight range of the airplane, and for all available configurations: all flap settings, and with the landing gear extended and retracted. They also determine operational speeds as multiples of the measured stall speed at a given operational weight. For takeoff flap settings, the minimum operational speed (V2) is usually 113% (1.13VS1G) of the stall speed for a given weight; and for approach and landing, the minimum speed (VRef) is 123% (1.23VS1G) of the stall speed.

The FAA certified the Q-400 via a Special Condition Issue Paper that allowed determination of the "1-G" stall speed rather than the minimum speed in the stall maneuver. Various transport airplanes were certified using this 1-G criterium, which in 2002 the FAA codified into 14 CFR part 25.103, Amendment 25-108. The issue paper included criteria for stall speed determination and stall warning criteria based on the redefinition of the stall speed as specified in the issue paper, and eventually codified it in Amendment 108 of 14 CFR part 25.

In addition to stall speed measurement, the FAA evaluates stall handling qualities, or "stall characteristics." For the Q-400, the FAA required stalls to be demonstrated per criteria specified in Amendment 25-84 of 14 CFR part 25.201 Stall Demonstration. The test pilots demonstrated stalls in all configurations, power on and off, in straight flight, and in turning flight at a bank angle of 30 degrees. During these demonstrations, the airplane is considered to be stalled under any of the following conditions:

- The airplane nose pitches down and that pitch down cannot be arrested

- There is a level of buffet that is a deterrent to further speed reduction

- The pitch control reaches the aft stop for a brief period with no further increase in pitch attitude

One or all of these criteria in combination, can define the stall endpoint. Per Amendment 25-84 of 14 CFR part 25.203, the airplane must remain controllable during the stall maneuver. The regulation also requires that the pilot must promptly prevent the stall by normal use of the controls. No control reversal or abnormal nose-up pitching may occur. Rolling (that is not induced by the pilot) cannot exceed 20 degrees in straight flight. For turning flight, depending on the stall entry rate, roll excursions can range from 30 to 60 degrees, but the regulation requires that roll excursions may not be violent or extreme enough as to make it difficult to affect a prompt recovery and regain control of the airplane.

Stall warning in all configurations and flight conditions also must occur at a sufficient margin above the stall speed to prevent inadvertent stalling and must be clear and distinctive to the pilot. 14 CFR part 25.207 provides the criteria for stall warning. Inherent warning (usually airframe buffet) is allowable if it occurs with sufficient margin and is recognizable in all flight conditions and configurations.

Historically, aerodynamic buffet has not been considered completely effective as a stall recognition criterion in all configurations, so engineers have employed other means, most often a "stick shaker." A stick shaker activates when the wing reaches a threshold angle of attack and causes a loud and easily recognizable vibration of the control column/wheel. The shaker remains "on" until the angle of attack reduces to a level below the onset threshold. This type of artificial device also provides a repeatable, consistent stall warning.

To prevent an actual stall, or to avoid conditions where stall handling qualities may be unacceptably degraded, some designs have employed a stall prevention device, generally referred to as a "stick pusher." A stick pusher operates at an angle of attack higher than the onset of other stall warning devices (such as a stick shaker), and physically inputs a large nose-down elevator force. If a pilot does not recognize or fails to respond appropriately to a stall warning device like a shaker, then at a programmed angle of attack, the stick pusher activates and applies a large nose-down control force in order to prevent further penetration into the stall maneuver. The pusher remains effective until the angle of attack reduces below the threshold level. The force of a stick pusher is considerable and generally sufficiently abrupt that a pilot will not resist its response. However, the force is not so great that the pilot cannot override it.

The Q-400 is equipped with both a stick shaker for stall warning and a stick pusher for stall prevention. However, as noted in the official accident report, when the stick pusher activated, the pilot flying made a large force input in the opposite (nose-up) direction, overriding the pusher, and thus prevented a reduction in the angle of attack.

14 CFR 25.201, Stall Demonstration

14 CFR 25.203, Stall Characteristics

14 CFR 121.542, Flight Crewmember Duties

14 CFR 121.544, Pilot Monitoring

SAFO 15011, Roles and Responsibilities for Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM)

AC 120-71, as amended, Standard Operating Procedures and Pilot Monitoring Duties for Flight Deck Crewmembers

Pilot Records Management

Before the Colgan accident, the Pilot Records Improvement Act of 1996 (PRIA) required employers to research the backgrounds of their pilot applicants through letters of request. Congress had formulated PRIA after there were numerous accidents where the air carrier did not have access to the pilot's background information. The PRIA law mandated that employers operating under 14 CFR part 121, 135, or 125 must request, receive and review the last five years of a pilot applicant's training, experience, qualification, and accident/enforcement history before making an offer of employment. The process was cumbersome, taking many weeks to wait for responses from different sources (FAA records, National Driver Registry, and previous air carrier records).

Pilot Records Management

Before the Colgan accident, the Pilot Records Improvement Act of 1996 (PRIA) required employers to research the backgrounds of their pilot applicants through letters of request. Congress had formulated PRIA after there were numerous accidents where the air carrier did not have access to the pilot's background information. The PRIA law mandated that employers operating under 14 CFR part 121, 135, or 125 must request, receive and review the last five years of a pilot applicant's training, experience, qualification, and accident/enforcement history before making an offer of employment. The process was cumbersome, taking many weeks to wait for responses from different sources (FAA records, National Driver Registry, and previous air carrier records).

The Colgan accident was a catalyst for improvements in several key safety initiatives, some involving long-standing cultural and organizational factors that were industry wide. The FAA made substantial changes regarding minimum pilot experience, pilot training, flight simulators, and pilot employment records. These requirements were levied to all airlines, including both major and regional carriers. See Resulting Safety Initiatives.

- Inadequate pilot training - At the time of the Colgan accident, pilots were not required to complete full stall recovery training, stick pusher familiarization, remedial training programs, training in manual handling techniques, runway maneuvers and pilot monitoring techniques. In addition, there were inadequate Airline Transport Pilot certificate training requirements.

- Excessive fatigue - New regulations were needed that used scientific information on pilot fatigue

- Lack of professionalism - The Colgan accident focused attention on deficiencies in training for pilot leadership and command and professional development.

- Lack of sterile cockpit adherence - Colgan flight crew members disregarded the prohibition from unnecessary conversations and activities which distracted them and caused them to lose situational awareness.

- Inadequate flight crewmember screening - The process for hiring and screening pilots was a cumbersome and ineffective means to access background and qualifications of pilot applicants and determining FAA certification failures. A poorly performing pilot may not be revealed prior to employment.

Teaching approach-to-stall recoveries in a simulator is adequate to prepare pilots for recovery from actual stalls in the airplane.

- The Colgan accident revealed that the approach-to-stall procedure was inadequate in preventing stall accidents. Congress then required that pilots experience full-stall recoveries in a simulator that accurately replicates the airplane's stall characteristics. The FAA then changed its stall recovery procedure.

Pilot performance history, background investigation, and training records for crewmembers will identify qualified pilots.

- While such information was required during the pilot hiring process, the procedure at the time of the accident was cumbersome and time-consuming and it did not include FAA certification failures.

Photo copyright Stuart Jessup - used with permission

Atlantic Coast Airlines Flight 6291, January 7, 1994, Jetstream 4101, Columbus, Ohio

A scheduled 14 CFR part 135 flight was on an ILS approach in instrument conditions at night. They were flying in light snow and fog and the airline had paired a new first officer with a new captain. According to company procedures, the minimum airspeed for the approach was 130 knots. The captain was late in configuring the airplane for the approach and it slowed below 130 knots while the first officer failed to warn the captain of the deteriorating airspeed.

At 400 feet and 104 knots, a brief stick shaker alerted the crew and the autopilot disengaged, as designed. The captain pulled the nose up without adding power and inappropriately retracted the flaps. The stick shaker began again and remained on for the rest of the flight while the pusher fired three times. During the stall, the airplane entered a series of pitch and roll excursions until it dropped onto a storage warehouse. The pilots, the flight attendant, and two passengers were killed. Three other passengers escaped before the plane was consumed by fire.

View: Atlantic Coast Airlines Flight 6291 Accident Report

Photo copyright Frank J. Mirande - used with permission

Airborne Express Test Flight, December 22, 1996, DC-8-63, Narrows, Virginia

The test flight with six crewmembers was about 10,000 feet above the ground and on top of an overcast layer when they began their stall series. Protocol called for the crew to perform the stalls during daylight, but due to a late start, it was dark. During the first clean stall maneuver, the stall buffet occurred but the stick shaker did not activate since the stall protection system was inoperative. The pilot flying added power but held the yoke back. The airspeed continued to decay, and the plane plunged downward through the clouds for one minute 32 seconds as the stall progressed with a series of roll reversals.

The pilot flying never pushed forward on the yoke to apply positive, nose-down control inputs in response to the stall. The NTSB believed this might have been because the pilots had practiced stalls in a DC-8 simulator that did not accurately reflect the airplane's stall characteristics. They descended out of the clouds 52° nose down, in a 113° right roll and hit mountainous terrain at 240 knots. All onboard were fatally injured in the impact and there was a post-crash fire.

Photo copyright Daniel Murzello - used with permission

Link to Accident Report: NTSB AAR 97-01

Pinnacle Flight 3701, October 14, 2004, Bombardier CL-600-2B19 (CRJ), Jefferson City, Missouri

While on a repositioning flight at night (with no passengers) the crew exhibited many unprofessional behaviors including swapping seats after takeoff. They intended to become a member of the "four-one-oh" club, so they zoomed up to 41,000 feet. This altitude was much too high for their weight and the aircraft stalled.

The inexperienced first officer was flying and incorrectly reacted to the stick shaker by pulling the nose up. The stick pusher fired four times, but each time he fought it by pulling back, thus holding the plane in a stall. The air at the engine inlets became turbulent from the high nose attitude and both engines flamed out. They depressurized due to the engine failures and descended, telling ATC that they had lost just "one engine," possibly worried about consequences with their company. The pilots made many attempts to restart; however, the engines had no rotation because they had seized and could not restart. They finally admitted to air traffic control that they had lost both engines and needed vectors to the nearest airport. By then they were too low to reach it and struck a garage 2.5 miles from the field. Both pilots were killed; no one was hurt on the ground.

Link to Accident Report: NTSB AAR 07-01

Following the Colgan accident, Colgan Air, Congress, and the FAA introduced numerous safety initiatives. The following is intended to capture the major safety initiatives undertaken since the accident.

Colgan Airline Actions

Ref Speeds Switch:

- Eight days after the accident, issued an Operations Bulletin that included two cautions regarding the Ref Speeds Switch

- Several weeks later, issued an Operations Bulletin that added a Ref Speeds Switch callout item to the Normal Checklist, which required a response from both flight crewmembers

- In February 2009, issued Operations Bulletin, "Speed Bugs for Landing, Icing Definitions, and Ice Equipment Operations," which:

- emphasized the importance of setting the proper speeds, especially when expecting icing conditions

- reiterated proper terminology to use with the onboard computer to ensure the pilots receive proper ice speeds

- introduced three levels of ice protection

- prohibited selecting the Ref Speeds Switch to the INCREASE position during takeoffs

- prohibited changing the position of the switch during landings and within 1,000 feet of the ground

- In March 2009, issued Operations Bulletin, "Ref Speeds Switch and Speed Guidance," which set specific target airspeeds during various segments of the approach phase of flight

Pilot Training:

- In April 2009, issued Operations Bulletin, "Q-400 Enhanced Flight Maneuvers Training," which:

- described the maneuvers added to initial, upgrade, transition, and recurrent training and checkrides

- added new stall recovery training that included autopilot disconnect, a stick pusher demonstration, and upset recovery training

- In August 2009, began a formal monitoring program for pilot training

- Revised its Crew Resource Management (CRM) training to make the program more robust and, in summer 2009, provided a two-day CRM course to pilots, dispatchers, flight attendants, and managers

- In September 2009, revised its Flight Operations Policies and Procedures Manual to contain a review of CRM and Threat and Error Management (TEM)

- Changed its line check policy so that all new captains would have a line check after six months

- Trained its check airmen to evaluate the performance of the monitoring pilot (in addition to the flying pilot) during checkrides

Fatigue:

- In April 2009, issued an Operations Bulletin that stated any crewmember who conducted a flight when fatigued, or otherwise physically incapable of completing a flight safely, would be in violation of company policy

- In September 2009 revised its Flight Operations Policies and Procedures Manual and added information about the company's fatigue policy

- Added a discussion of fatigue in their new CRM program

- In December 2009, the Director of Operations issued a read-and-sign memo, "Interim Fatigue Policy," that:

- stated pilots were abusing their non-punitive fatigue policy

- contained revised fatigue policy information

- limited fatigue calls under certain situations

- threatened disciplinary action for blatant abuse of the fatigue policy

- announced they would have a comprehensive fatigue program by February 2010

Hiring Policies:

- In April 2009, required newly-hired pilots to have 1,000 hours total flight time and 100 hours in multi-engine aircraft

- Required Q-400 captains to have 3,500 hours total flight time and one of the following: 1,000 hours as a pilot-in-command at Colgan, 1,500 hours in aircraft type, or 2,000 hours at Colgan

- Required Saab 340 captains to have 2,500 hours total flight time and 1,000 hours at Colgan

Sterile Cockpit:

- Added a recurrent training slide addressing adherence to sterile cockpit procedures

- In February 2009, the Chief Pilot issued a message addressing sterile cockpit adherence

- In September 2009, added a checklist item for the 10,000-foot sterile cockpit period and expanded the sterile cockpit period to include (1) 1,000 feet above or below a level-off altitude and (2) approaching the top of descent on crossing restrictions and pilot-discretion descents

Voluntary Safety Programs:

- During summer and fall 2009, conducted an Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP) "re-emphasis campaign" for all crew bases

- Trained additional Line Operations Safety Assessments (LOSA) observers and planned to complete at least 100 LOSA observations by the end of the first quarter of 2010

- Equipped 14 Q-400s with quick access recorders (QARs) by January 2010 to initiate their FOQA program

Additional Post-Accident Actions:

Required dispatchers to check the icing box on the dispatch release if icing conditions existed in either the departure or arrival city

Increased flight operations management at crew bases

Safety department personnel conducted monthly observations of crew bases and observed flight crews during line operations

Increased the surveillance by Q-400 check airmen as part of a "standardization push"

Required pilots to ride with a check airman after an infraction

Implemented a zero-tolerance policy that held pilots accountable for "egregious" mistakes

Increased communications to flight crews for each event or challenge a crew had encountered

Reviewed their top-of-descent to touchdown phase of flight for both of their fleets

In September 2009, introduced their "VVM Program" (Verbalize, Verify, and Monitor)

Congressional Actions

PUBLIC LAW 111-216, AUGUST 1, 2010

After Congress unanimously passed its safety provisions, on August 1, 2010 President Barack Obama signed Public Law No: 111-216, the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010. Below is a summary of the provisions of the law for both FAA-required actions along with the measures the FAA implemented.

Congressional Actions

PUBLIC LAW 111-216, AUGUST 1, 2010

After Congress unanimously passed its safety provisions, on August 1, 2010 President Barack Obama signed Public Law No: 111-216, the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010. Below is a summary of the provisions of the law for both FAA-required actions along with the measures the FAA implemented.

SECTION 202: SECRETARY OF TRANSPORTATION RESPONSES TO SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

The Secretary shall submit to Congress and the Board, on an annual basis, a report on the recommendations made by the Board to the Secretary regarding air carrier operations conducted under Part 121 of title 14, Code of Federal Regulations. This report is to include for each NTSB recommendation:

- a description of the recommendation;

- a description of the procedures planned for adopting the recommendation or part of the recommendation;

- the proposed date for completing the procedures; and,

- if the Secretary has not met a deadline contained in a proposed timeline developed in connection with the recommendation an explanation for not meeting the deadline,

- a description of the reasons for the refusal to carry out all or part of the procedures to adopt the recommendation

DOT ACTIONS: Report to Congress on Secretary of Transportation Responses to NTSB Recommendations, December 1, 2011

SECTION 203: FAA PILOT RECORDS DATABASE

Requires the FAA Administrator to establish an electronic database of FAA Records for Parts 121, 125 and 135, air carrier records, and also the National Driver Register records of all pilots and prospective pilots. The air carrier must evaluate all of these records before they hire a pilot.

FAA Actions: Before the Colgan accident the Pilot Records Improvement Act of 1996 (PRIA) required employers to research the backgrounds of their pilot applicants through letters of request. Congress had formulated PRIA after there were numerous accidents where the air carrier did not have access to the pilot’s background information. The PRIA law mandated that employers operating under 14 CFR part 121, 135, or 125 must request, receive, and review the last five years of a pilot applicant’s training, experience, qualification and accident/enforcement history before making an offer of employment. The process was cumbersome, taking many weeks to wait for responses from different sources (FAA records, National Driver Registry and previous air carrier records).

After Colgan, Congress required a more rapid process and amended PRIA to utilize a web-based, online Pilot Records Database (PRD). The PRD electronically automates the PRIA process and employers may use it in lieu of completing the manual PRIA requests. Plans called for the FAA to deploy the PRD in multiple phases through the early 2020's while continuing to conduct rulemaking and technological upgrades to other portions of the database.

The FAA deployed Phase I of the PRD in December 2016. Use of Phase I was voluntary and provided only FAA records for the air carrier or operator. Under Phase I, employers still had to request paper records from current and previous employers and from the National Driver Registry.

During Phase 2, air carriers and operators are strongly encouraged to access the PRD. When the FAA releases Phase 3, air carriers and operators will be required to utilize the database.

- InFO 11014, Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 91, 121, 125 and 135 Retention of Pilot Records for the Pilot Records Database (PRD), August 15, 2011

- InFO 14005, Pilot Records Database (PRD) Status Update, March 13, 2014

- AC 120-68G, Pilot Records Improvement Act of 1996, June 21, 2016

- InFO 17019, Beta Release of the Pilot Records Database (PRD), December 7, 2017

- InFO 18005, Expanded Beta Release of the PRD, May 21, 2018

SECTION 204: FAA TASK FORCE ON AIR CARRIER SAFETY AND PILOT TRAINING

Requires the FAA Administrator to establish a task force to evaluate air carrier recommendations for flight crewmember education and support and professional and training standards. The Administrator is to submit an annual report to Congress detailing their progress and recommendations for legislative or regulatory actions.

The duties of the Task Force shall include, at a minimum, evaluating best practices in the air carrier industry and providing recommendations in the following areas:

- Air carrier management responsibilities for flight crew member education and support

- Flight crew member professional standards

- Flight crew member training standards and performance

- Mentoring and information sharing between air carriers

FAA Actions: The FAA Administrator and the Secretary of Transportation conducted a series of Call-to-Action safety forums with airlines and labor unions, aimed at strengthening safety standards. Eighty-two percent of US air carriers representing 99% of the commercial fleet and seven pilot unions responded. The hearings highlighted the differences between mainline and regional operators and their differing safety records. The FAA’s Call to Action Plan focused on reducing risks at all air carriers; promoting best practices from mainline to regional carriers; and seeking industry compliance with safety initiatives that involved pilot training, fatigue management, and pilot professionalism.

In September 2010, the FAA formed an Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC), the Air Carrier Safety and Pilot Training ARC, to address the four requirements of Section 204 of the Law.

On July 31, 2011, the task force developed and delivered to Congress the required report of these meetings. The narrative contained recommendations for airline best practices and those recommendations that needed legislative or regulatory action. The report also established that airlines who follow these recommended safety practices will help foster a positive safety culture.

- InFO 10002, Industry Best Practices Reference List, March 16, 2010

- InFO 10002 SUP, Industry Best Practices Reference List Supplement, March16, 2010

- Air Carrier Safety and Pilot Training Aviation Rulemaking Committee, September 15, 2010

- Report from the Air Carrier Safety and Pilot Training Aviation Rulemaking Committee, July 31, 2011

SEC. 205: AVIATION SAFETY INSPECTORS AND OPERATIONAL RESEARCH ANALYSTS

The Inspector General (IG) of the Department of Transportation shall conduct a review of the aviation safety inspectors and operational research analysts of the Federal Aviation Administration assigned to Part 121 air carriers and submit to the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration a report on the results of the review.

IG Report: The Inspector General’s audit found that the FAA employs approximately 4,000 aviation safety inspectors and 40 analysts. Due to concerns raised after the Colgan Air accident, the IG evaluated how the FAA assigns inspectors to Part 121 carriers, including assessing the number and experience levels of inspectors and analysts. The FAA had introduced a new inspector-staffing model in 2009, but they had not fully relied on the model’s results to determine the number and placement of inspectors needed. The IG made seven recommendations to enhance the FAA’s inspector-staffing model and the FAA considered the suggestions resolved.

SEC. 206: FLIGHT CREW MEMBER MENTORING, PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND LEADERSHIP

Shall convene an ARC to take the following action:

- Establish flight crew member mentoring programs under which the air carrier will pair highly experienced flight crew members who will serve as mentor pilots with newly employed flight crew members. Mentor pilots should be provided, at minimum, specific instruction on techniques for instilling and reinforcing the highest standards of technical performance, airmanship, and professionalism in newly employed flight crew members.

- Establish flight crew member professional development committees made up of air carrier management and labor union or professional association representatives to develop, administer, and oversee formal mentoring programs of the carrier to assist flight crew members to reach their maximum potential as safe, seasoned, and proficient flight crew members

- Establish or modify training programs to accommodate substantially different levels and types of flight experience by newly employed flight crew members

- Establish or modify training programs for second in command flight crew members attempting to qualify as pilot in command for the first time in a specific aircraft type and ensure that such programs include leadership and command training

- Ensure that recurrent training for pilots in command includes leadership and command training

- Such other actions as the aviation rulemaking committee determines appropriate to enhance flight crew member professional development

Compliance with sterile cockpit rule: leadership and command training described in paragraphs (d) and (e) shall include instruction on compliance with flight crew member duties under Part 121.542 of Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations.

FAA Actions:

The FAA issued the final rule, Pilot Professional Development, on February 25, 2020. By April 27, 2022, air carriers must have in place:

- Leadership and command curriculum and mentoring curriculum during pilot-in-command initial and upgrade training

- Second-in-command to pilot-in-command upgrade curriculum

- Operations familiarization for newly hired pilots

- By April 27, 2023, a one-time leadership and command training and mentoring training for current pilots-in-command

The revised performance-based curriculum requirements ensure pilots-in-command (PICs) have technical knowledge and skills, while focusing on the decision-making and leadership skills required of a PIC. The mentoring training provides all PICs with techniques for instilling and reinforcing the highest standards of technical performance, airmanship, and professionalism in newly employed pilots. This rule satisfied Congress requirement for FAA rulemaking in section 206 of Public Law 111-216. The benefits of this required training ensure that carriers reduce the risk of unprofessional pilot behavior and thus avoid situations that can lead to a catastrophic event. Investigators determined that unprofessional pilot behavior contributed to the accident of Colgan Air flight 3407.

The Professional Pilot Development Rule applies to certificate holders who train and qualify pilots under Part 121 subparts N and O (traditional) and under subpart Y (AQP). It also affects Part 135 air carriers / operators and Part 91K program managers who train their pilots under Part 121 Subpart N and O. The rule responds to NTSB recommendations A-10-013 (Issue an Advisory Circular with guidance on leadership training for upgrading captains at Part 121, 135 and 91K operators) and A-10-014 (Require all Part 121, 135 and 91K operators to provide a specific course on leadership training to their upgrading captains).

- InFO 10003, Cockpit Distractions, April 26, 2010

- AC 120-74, as amended, Parts 91, 121, 125 and 135 Flight crew Procedures during Taxi Operations, July 30, 2012

- InFO 14006, Prohibition of Personal Use of Electronic Devices on the Flight Deck, May 20, 2014

- SAFO 15011, Roles and Responsibilities for Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM), November 17, 2015

- AC 120-71, as amended, Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) and Pilot Monitoring Duties, January 10, 2017

- AC 135-43, as amended, Part 135 Second in Command Professional Development Program, June 28, 2018

- Final Rule: Pilot Professional Development (85 FR 10896), February 25, 2020

- AC 121-42, as amended, Leadership and Command Training for Pilots in Command, (to be published the week of 04/27/20)

- AC 121-43, as amended, Mentoring Training for Pilots in Command, (to be published the week of 04/27/20)

SEC. 207: FLIGHT CREW MEMBER PAIRING AND CREW RESOURCE MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES

Study - The Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration shall conduct a study on aviation industry best practices with regard to flight crew member pairing, crew resource management techniques, and pilot commuting.

FAA Actions: The FAA had been promoting many of the recommended best practices. These include the use of voluntary programs, including the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP), which encourages aviation employees to report unsafe conditions; the Advanced Qualification Program (AQP), an alternative to traditional training requirements; and the Line Oriented Safety Assessments (LOSA), where pilots observe other pilots of their company while inflight.

The FAA also issued the final rule, Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers, on November 12, 2013 (78 FR 67799). This rule revises and enhances the training requirements for pilots in air carrier operations. It emphasizes the development of pilots’ manual handling skills and adds safety-critical tasks such as recovery from stall and upset. The final rule also requires enhanced runway safety training and pilot monitoring training be incorporated into existing requirements for scenario-based flight training. It obliges air carriers to implement remedial training programs for pilots. Additionally, the rule provides civil enforcement authority for making fraudulent statements, along with a number of technical changes to existing air carrier training requirements. The FAA expects that these changes will contribute to a reduction in aviation accidents.

SEC. 208: IMPLEMENTATION OF NTSB FLIGHT CREW MEMBER TRAINING RECOMMENDATIONS

The FAA Administrator is to conduct rulemaking to require Part 121 air carriers to provide flight crew members with ground and flight or flight simulator training on stall and upset recognition and recovery training.

The FAA is going to conduct rulemaking to require Part 121 air carriers to establish remedial training programs for flight crew members who have demonstrated performance deficiencies or have experienced failures in the training environment.

Additionally, the FAA is to convene a multidisciplinary panel of specialists in aircraft aviation safety to study and submit a report on methods to improve the response of flight crew members to stick pusher systems, icing conditions and microburst and windshear weather reports.

FAA Actions: The FAA chartered the Stick Pusher and Adverse Weather Event Training (SPAW) Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) on September 30, 2010. Their task was to make recommendations on the best methods to improve pilots' response to stick pusher systems, icing conditions and microburst, and windshear weather events.

Many of the SPAW ARC had also served on the Stall and Stick Pusher Work Group, chartered March 11, 2010, the group that developed the new procedure for stall recovery and for training on the stick pusher. In August 2012, the FAA harmonized with industry to define the new procedure for impending and full stalls through Advisory Circular (AC) 120-109, "Stall and Stick Pusher Training." While the FAA developed this AC for Part 121 air carriers, they urged all airplane operators and pilot schools to use this guidance for stall training, testing, and checking, as the principles apply to all airplanes.

The ARC also addressed the fact that the current performance envelopes of flight simulation training devices (FSTD) or full flight simulators, (FFS) were unable to perform these maneuvers accurately.

The SPAW ARC then suggested that 14 CFR part 60 be modified for new standards of level A through D FFS fidelity for flight in icing, microbursts, windshear, stall and stick pusher training, takeoffs and landings in gusting crosswinds and bounced landing recovery maneuvers. Additionally, they recommended both academic and flight training for upset prevention and recovery, based on the Airplane Upset Recovery Training Aid (Revision 2). The NTSB also issued recommendations for training in the above maneuvers.

The FAA issued the Final Rule, Flight Simulation Training Device Qualification Standards for Extended Envelope and Adverse Weather Event Training on March 30, 2016 (81 FR 18177) This rule requires new technical evaluation standards for Level A through D FFS and flight training devices (FTD) that are approved under 14 CFR part 60.

The FAA's Final Rule: Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers, November 12, 2013 (78 FR 67800) now requires these advanced maneuvers to be taught by March 12, 2019, thus the new simulator fidelity was necessary.

- Airplane Upset Recovery Training Aid, Revision 2, November 2008

- SAFO 10012, Possible Misinterpretation of the Practical Test Standards (PTS) Language "Minimal Loss of Altitude," July 6, 2010

- InFO 10010, Enhanced Upset Recovery Training, July 6, 2010

- Final Rule: Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers, November 12, 2013 (78 FR 67800)

- InFO 15004, Use of Windshear Models in Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Qualified Flight Simulation Training Devices (FSTD), March 13, 2015

- AC 121-39, Air Carrier Remedial Training and Tracking Program, December 30, 2014

- AC 120-109A, Change 1: Stall Prevention and Recovery Training, January 4, 2017

- Final Rule: Flight Simulation Training Device Qualification Standards for Extended Envelope and Adverse Weather Event Training Tasks, 14 CFR part 60, March 30, 2016 (81 FR 18178)

- SAFO 17007, Manual Flight Operations Proficiency, May 4, 2017

- AC 120-111, Change 1, Upset Prevention and Recovery Training, January 4, 2017

- InFO 17017, Enhanced Pilot Training and Qualification for Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 121 Pilots, November 20, 2017

Photo copyright Ethan Arnold - used with permission

PART 209: FAA RULEMAKING ON TRAINING PROGRAMS

The FAA is to issue a final rule for the NPRM issued on January 12, 2009 (74 FR 1280) relating to training programs for flight crew members and aircraft dispatchers.

FAA Actions: Shortly after publication of the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers, the Colgan Air crash happened. Congress then directed the FAA to conduct rulemaking to ensure that all flight crew members receive ground training and flight training in recognizing and avoiding stalls, recovery from stalls and recognizing, avoiding and recovery techniques of an aircraft upset.

Public Law 111-216 also directed the FAA to conduct rulemaking to ensure air carriers develop remedial training programs for flight crew. In light of this, the FAA published the final rule on November 12, 2013, entitled, Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers (78 FR 67800).

The new regulations enhance pilot training programs for air carrier pilots. They emphasize the development of pilots’ manual handling skills (upset recovery maneuvers, slow flight, stalls, recovery from stick pusher activation and loss of reliable airspeed.) The rule also requires enhanced runway safety training (expanding taxi and pre-takeoff requirements, crosswind maneuvers to include gusts and bounced landings) and pilot monitoring. All these maneuvers should be incorporated into scenario-based flight training. The rule also grants civil enforcement for making fraudulent statements.

- SAFO 10009, Safety Management System (SMS) Principals, Training and Pilot Skill Level Tracking, June 23, 2010

- Final Rule: Qualification, Service and Use of Crewmembers and Aircraft Dispatchers, November 12, 2013 (78 FR 67800)

- AC 120-71B, Standard Operating Procedures and Pilot Monitoring Duties for Flight Deck Crewmembers, January 10, 2017

SECTION 210: DISCLOSURE OF AIR CARRIERS OPERATING FLIGHTS FOR TICKETS SOLD FOR AIR TRANSPORTATION

Congressional Actions: On August 1, 2010, Public Law 111-216 immediately amended Title 49 of the United States Code, Section 41712. It added the requirement, "It is an unfair or deceptive practice to sell tickets on a flight of an air carrier if they fail to disclose the name of the air carrier providing the air transportation and it shall be provided on the first display of the website, easily visible to the viewer."

Thus, when the passengers for the Colgan Flight 3407 purchased their tickets, they would have only seen: Continental Airlines. Under the new law, the itinerary would have said, Continental Airlines, operated by Colgan Air.

SECTION 211: SAFETY INSPECTIONS OF REGIONAL AIR CARRIERS

Once a year the FAA is to conduct yearly, random, onsite inspections of air carriers under Part 121. This is to ensure that such air carriers are complying with all applicable safety standards of the FAA.

SECTION 212: PILOT FATIGUE

This section directs the FAA to develop regulations based on the best available scientific information to provide limitations on the hours of flight and duty time for pilots to address problems relating to pilot fatigue, including the effects of commuting on pilot fatigue.

These regulations are to also include each airline developing a Fatigue Risk Management Plan (FRMP). This plan is an airline's policies and procedures for reducing the risks of a flight crew member's fatigue, based on the type of its operation.

FAA Actions: At the time of the Colgan accident, the flight and duty regulations were not consistent across different types of flights and did not take into account start time and time zone crossings. The new rule sets a ten-hour minimum rest period prior to flight, which was a two-hour increase. It also mandates a pilot have eight hours of uninterrupted sleep, where it used to require only eight hours between leaving the aircraft and returning to it for the next flight.

The new rule also addresses cumulative fatigue by placing both weekly and 28-day limits on flight time, including at least thirty consecutive hours free from duty each week, which is a 25% increase over the previous rules.

The FAA now expects both pilots and airlines to take joint responsibility to ensure a pilot is fit for duty, including fatigue from commuting. Prior to each flight segment, a pilot must sign that he or she is fit for duty and if they are fatigued, the airline must immediately remove them from duty.

One provision of Part 117 is an initial fatigue and awareness-training program for pilots that must be FAA approved. This important provision of Part 117 is the Fatigue Risk Management Plan (FRMP), which the FAA also approves. This describes how an air carrier will manage, monitor and mitigate day-to-day pilot fatigue, including scheduling, fatigue reporting policies and pilot education. The carrier must update the FRMP with the FAA every two years.

- SAFO 09014, Concepts for Fatigue Countermeasures in Part 121 and 135 Short- Haul Operations, September 11, 2009

- AC 120-100, Basics of Aviation Fatigue, June 7, 2010

- InFO 10013, Fatigue Risk Management Plans (FRMP) for Part 121 Air Carriers, Part 1, August 12, 2010

- InFO 10017, Fatigue Risk Management Plans (FRMP) for Part 121 Air Carriers, Part 2, August 19, 2010

- InFO 10017 SUP, Fatigue Risk Management Plans (FRMP) for Part 121 Air Carriers, Part 2, August 19, 2010

- Final Rule: Flight crew Member Duty and Rest Requirements, 14 CFR parts 117, 119 and 121, January 4, 2012 (77 FR 330)

- AC 117-2, Fatigue Education and Awareness Training Program, October 11, 2012

- AC 117-3, Fitness for Duty, October 11, 2012

- Clarification of Final Rule: Flight crew Member Duty and Rest Requirements, March 5, 2013 (78 FR 14166)

- AC 120-103A, Fatigue Risk Management Systems for Aviation Safety, May 6, 2013

- InFO 13008, Required Updates to Fatigue Risk Management Plans (FRMP), May 15, 2013

- AC 117-1, Change 1, Flight crew Member Rest Facilities, August 21, 2013

- InFO 15001, Fatigue Education and Awareness Training Programs Required by 14 CFR part 117.9, January 14, 2015

SECTION 213: VOLUNTARY SAFETY PROGRAMS

Congress directed the FAA to provide a report to Congress on which air carriers were using one or more of the voluntary safety programs. This included the aviation safety action program (ASAP), the flight operational quality assurance program (FOQA), the line operations safety audit (LOSA) and the advanced qualification program (AQP).

Additionally, the report had to explain where the data from the programs is stored, how the data are protected and secured and what data analysis processes air carriers were implementing for effective use of the data.

FAA Actions: The FAA reported that of the 94 Part 121 operators, 64 (68%) participate in at least 1 voluntary program and 42 (45%) participate in more than one. Thirty-eight operators (40%) have 15 or fewer aircraft. Of those small operators, only sixteen have at least one voluntary program.

The Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) initiative proactively identifies safety trends and assesses the impact of changes in the aviation-operating environment. When ASIAS was initiated, FOQA and ASAP data were stored on the participants' facilities and not at a central location. As the program has matured, the architecture has evolved. Based on costs, maintenance, and efficiency, participants that are more recent have agreed to have their proprietary data stored in a central location as long as the FAA adequately protects the data. Some of the original participants have nodes at their sites (a distributed network) while those that joined ASIAS most recently store their data at a centralized repository, currently the FAA's FFRDC, MITRE/CAASD.

Information System Security (ISS) is a critical component of ASIAS. The security for ASIAS meets all Federal standards. The FAA established a secure infrastructure to protect the sensitive participant data and other data as well as the ASIAS network as a whole. This includes the installation of dedicated firewalls, intrusion detection equipment, and anti-virus protection software at participants' nodes as well as at the central site. ASIAS ISS is a continuous process that is monitored daily. Security for ASIAS is assured by maintaining the entire production network as a separate entity, with no connection to the Internet. ARINC maintains this network. User access to the system uses both operating-system-based user authentication and permissions functionality within the underlying database to control access to data.

- AC 120-66B, Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP), November 15, 2002

- AC 120-51E, Crew Resource Management (CRM) Training, January 22, 2004

- AC 120-90, Line Operations Safety Audits (LOSA), April 27, 2006

- AC 120-54A with Change 1, Advanced Qualification Program (AQP), January 31, 2017

- FAA Report to Congress on Voluntary Safety Programs, January 28, 2011

- AC 120-35D, Flight crew Member Line Operational Simulations: Line Oriented Flight Training, Special Purpose Operational Training, Line Operational Evaluation, March 13, 2015

SECTION 214: ASAP AND FOQA IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

The Administrator is directed to develop and implement a plan to facilitate the establishment of an aviation safety action program (ASAP) and a flight operational quality assurance program (FOQA) by all Part 121 air carriers. The Administrator shall consider:

- How the Administration can assist Part 121 air carriers with smaller fleet sizes to derive a benefit from establishing a flight operational quality assurance program.

- How Part 121 air carriers with established aviation safety action and flight operational quality assurance programs can quickly begin to report data into the aviation safety information analysis sharing database: and