Air Mail Pioneers

The postal system played a key role in the early history of U.S. civil aviation. On May 15, 1918, the Post Office inaugurated the Nation's first continuous scheduled air mail service between cities (Washington, Philadelphia, and New York).

A Curtiss JN4-H prepares to carry mail on a northward flight from Washington's Polo Field. Another mail plane headed south from New York to begin the first air mail route.

After initial help from the Army, the postal authorities took full responsibility for air mail operations and began to expand the system. They undertook the establishment of lighted airways and pioneered the techniques of airway flying.

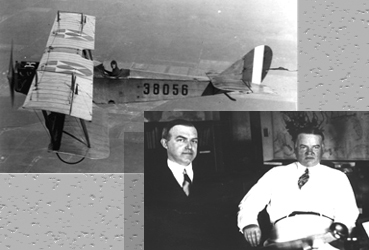

Besides its importance in developing the technical side of air transportation, air mail offered a material incentive. In 1925, Congress gave a much-needed boost to America's struggling airlines by authorizing them to carry the mail on a contractual basis. Shown at left is a Boeing 40-C mail plane operated by Universal Air Lines.

Besides its importance in developing the technical side of air transportation, air mail offered a material incentive. In 1925, Congress gave a much-needed boost to America's struggling airlines by authorizing them to carry the mail on a contractual basis. Shown at left is a Boeing 40-C mail plane operated by Universal Air Lines.

MacCracken and the Aeronautics Branch

William P. MacCracken, Jr., was the first head of FAA's earliest predecessor agency, the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce. In the upper photo at right, he is shown flying for the Army in 1917.

William P. MacCracken, Jr., was the first head of FAA's earliest predecessor agency, the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce. In the upper photo at right, he is shown flying for the Army in 1917.

Returning to his civilian career as a lawyer, MacCracken became an advocate of Federal safety regulation of aviation. After this campaign succeeded, he became Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aviation on August 11, 1926. On that day, MacCracken posed for a photo (right) with his new boss, Secretary Herbert Hoover.

Safety Certification Begins

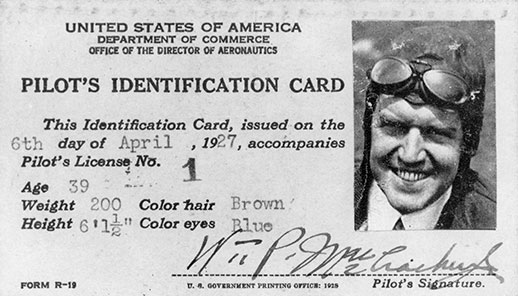

The Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce began pilot certification with this license, issued on April 6, 1927. The recipient was the chief of the Branch, William P. MacCracken, Jr. Orville Wright, who was no longer an active flier, had declined the honor.) MacCracken's license was the first issued to a pilot by a civilian agency of the Federal government.

Some three months later, the Branch issued the first federal aircraft mechanic license.

Equally important for safety was the establishment of a system of certification for aircraft. On March 29, 1927, the Aeronautics Branch issued the first airworthiness type certificate to the Buhl Airster CA-3, a three-place open biplane. The Airster is shown below in a 1926 photograph. (National Archives photo)

Building the Airways

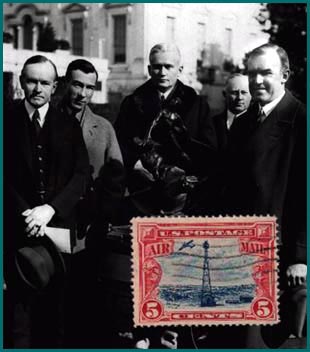

Pictured (left to right) are: Pres. Coolidge; Dir. of Aeronautics Clarence Young; Sen. Hiram Bingham; an unidentified person; and Assist. Sec. of Commerce William P. MacCracken, Jr.

Pictured (left to right) are: Pres. Coolidge; Dir. of Aeronautics Clarence Young; Sen. Hiram Bingham; an unidentified person; and Assist. Sec. of Commerce William P. MacCracken, Jr.

Responsibility for establishing a system of lighted airways passed from the Post Office to the new Aeronautics Branch after its creation in 1926. On January 14, 1929, the Branch received the Robert J. Collier Trophy in recognition of its work in developing the Nation's air navigation system. Fifteen days after the award ceremony pictured here, the Branch completed the lighting of the transcontinental airway.

![]() Enthusiasm for the new aerial highways was reflected in the 5 cent air mail stamp of 1928. One of the light beacons used to mark the airways is shown on the stamp and in the photo to the left.

Enthusiasm for the new aerial highways was reflected in the 5 cent air mail stamp of 1928. One of the light beacons used to mark the airways is shown on the stamp and in the photo to the left.

Built at intervals of approximately 10 miles, the standard beacon tower was 51 feet high, topped with a powerful rotating light. Below the rotating light, two course lights pointed forward and back along the airway. The course lights flashed a code to identify the beacon's number.

The tower usually stood in the center of a concrete arrow 70 feet long. A generator shed, where required, stood at the "feather" end of the arrow.

Another feature of the early airways were intermediate landing fields. Federal authorities established these facilities where needed to ensure that pilots could land safely at intervals of approximately 50 miles along their route. The fields were usually colocated with light beacons, as shown in this scene from the late 1920s or early 1930s. The conical object at left is a boundary marker light. (National Archives photo)

Those who constructed the airways often faced adverse weather and terrain. In remote areas of the Southwest, burros played an important role in transporting equipment and materials. When slopes proved too rugged for even these sure-footed animals, the Airways Division built "trolley lines" to haul material along cables mounted on poles.

Those who constructed the airways often faced adverse weather and terrain. In remote areas of the Southwest, burros played an important role in transporting equipment and materials. When slopes proved too rugged for even these sure-footed animals, the Airways Division built "trolley lines" to haul material along cables mounted on poles.

To limit expenses, Secretary of Commerce Hoover assigned many of the new aviation responsibilities to existing organizations within his Department. The Airways Division, for example, was structurally part of the Bureau of Lighthouses. This arrangement continued until July 1933, when the Aeronautics Branch assumed sole responsibility for the airways.

To limit expenses, Secretary of Commerce Hoover assigned many of the new aviation responsibilities to existing organizations within his Department. The Airways Division, for example, was structurally part of the Bureau of Lighthouses. This arrangement continued until July 1933, when the Aeronautics Branch assumed sole responsibility for the airways.

In this 1931 photo, the "Lighthouse" designation appears above the door of the airway station at Elko, Nevada.

Keeping the airways in operating condition was always a demanding task, but not without its lighter moments. Technician "Dusty" Rhodes is shown relaxing beside his truck in this photo from the late 1930s. He is wearing the uniform of airway station keepers during that era.

In the late 1920s, the Aeronautics Branch began establishing a new type of navigational aid, the low frequency radio range (LFR), also know as the four-course radio range. This type of facility could provide guidance even when poor visibility made light beacons useless.

In the late 1920s, the Aeronautics Branch began establishing a new type of navigational aid, the low frequency radio range (LFR), also know as the four-course radio range. This type of facility could provide guidance even when poor visibility made light beacons useless.

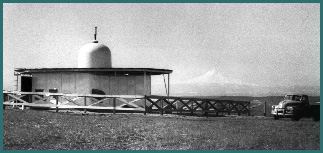

By comparing two coded signals generated by an LFR, pilots could tell whether they were drifting to the left or right of an airway. For those flying on course, the two signals merged into a single tone. The range shown above, at Northway, Alaska, was the last LFR to continue in operation. (National Archives photo)

By the time the Northway range fell silent in 1974, a new type of navigation facility had long dominated the airways: the Very High Frequency Omnidirectional Radio Range (VOR). Based on technology developed during World War II, the VOR enabled the pilots of instrument-equipped planes to determine their position more efficiently. The Civil Aeronautics Administration commissioned the first VOR in 1947, and three years later opened the first "Victor" airways based on chains of the facilities. Modernized versions of these navigation aids still guide pilots to their destinations.

By the time the Northway range fell silent in 1974, a new type of navigation facility had long dominated the airways: the Very High Frequency Omnidirectional Radio Range (VOR). Based on technology developed during World War II, the VOR enabled the pilots of instrument-equipped planes to determine their position more efficiently. The Civil Aeronautics Administration commissioned the first VOR in 1947, and three years later opened the first "Victor" airways based on chains of the facilities. Modernized versions of these navigation aids still guide pilots to their destinations.

Airway Communications

In 1927, the Aeronautics Branch took over 17 aeronautical radio stations from the Post Office Department. The Branch soon began to establish more of these facilities, which served as gathering points for data on weather and flights to be used in briefing pilots. The stations transmitted this information along the airways by radio and later by teletype via ground lines.

At right is the St. Louis Airway Radio Station during the late 1920s or early '30s. Barely visible in the photo is the wire strung between the tops of its twin antenna towers. During this era, some stations were making hourly weather broadcasts. When needed for safety, they also accepted messages from the airlines and transmitted them to pilots aloft.

At right is the St. Louis Airway Radio Station during the late 1920s or early '30s. Barely visible in the photo is the wire strung between the tops of its twin antenna towers. During this era, some stations were making hourly weather broadcasts. When needed for safety, they also accepted messages from the airlines and transmitted them to pilots aloft.

The photo at left shows the interior of the Airway Radio Station at Portland, Oregon, about 1929. Carl Anderson examines a strip of the code in which the station operators made most of their transmissions during this period.

The photo at left shows the interior of the Airway Radio Station at Portland, Oregon, about 1929. Carl Anderson examines a strip of the code in which the station operators made most of their transmissions during this period.

The view at right dates from about 1940, when the evolving facilities were known as Interstate Airway Communication Stations (INSACs). Women often staffed the stations, particularly during the World War II era.

The view at right dates from about 1940, when the evolving facilities were known as Interstate Airway Communication Stations (INSACs). Women often staffed the stations, particularly during the World War II era.

The names, procedures, and equipment of the facilities continued to change with the advance of technology. Today's Automated Flight Service Stations have inherited their mission of keeping pilots abreast of safety-related information.

Aeronautics Branch Aircraft

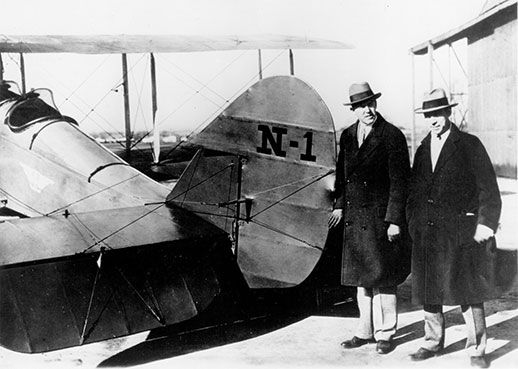

In 1927, the Aeronautics Branch acquired this De Haviland D.H.4b, a former mail plane. The numeral on its tail indicates that this was probably the first aircraft to receive a registration number from the Branch. (The letter "N" had been assigned to the United States by international agreement in 1919.)

Standing next to the aircraft is William P. MacCracken, Jr., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics. To the right is Clarence Young, who was MacCracken's deputy and later his successor as head of the Aeronautics Branch. (National Archives photo)

The Aeronautics Branch used most of its fleet for aerial inspection of navigation aids, a function that has continued to the present day.

The Aeronautics Branch used most of its fleet for aerial inspection of navigation aids, a function that has continued to the present day.

One such aircraft was the Stearman C-3B biplane, shown at left in 1929 or 1930. (Museum of Flight photo)

Another early example of the Aeronautics Branch aircraft is this Bellanca Pacemaker E. The Branch bought nine of this type in 1929, and assigned five to the Airways Division. For a history of flight inspection, see Scott A. Thompson's book Flight Check!, an FAA publication.

Vidal and the Bureau of Air Commerce

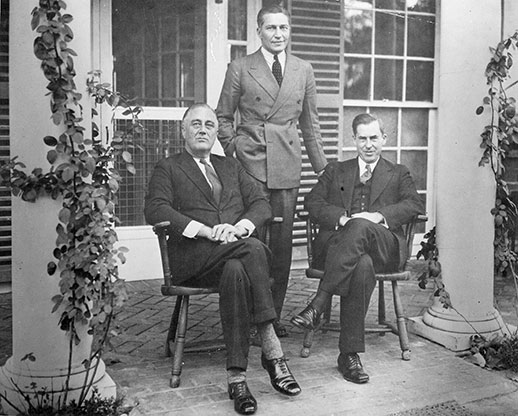

The third head of the Aeronautics Branch, Eugene L. Vidal, is flanked by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace (right). The photograph was taken in 1933 at the President's favored spa in Warm Springs, Ga.

During Vidal's tenure, the Aeronautics Branch was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce on July 1, 1934. The new name more accurately reflected the status of the organization within the Department of Commerce. The Bureau remained aviation's safety regulator until the creation of the Civil Aeronautics Authority in 1938.