Lockheed L-1011

Copyright Steve Brimley - used with permission

Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 163, HZ-AHK

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

August 19, 1980

On August 19, 1980, Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 163, L-1011 registration number HZ-AHK, took off from the airport at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Seven minutes after take-off an aural warning indicated smoke in the aft cargo compartment. In response to information received from the flight attendants, the flight engineer went into the passenger cabin and reported back that there was fire and smoke emanating from the extreme aft area of the cabin, directly above the C-3 cargo compartment. The captain decided to return to Riyadh. During the return flight, the flight attendants attempted to fight the fire, which had burned through the cabin floor, with available handheld extinguishers. The aircraft landed back at Riyadh some 20 minutes later, and did not make an emergency stop, but instead taxied off the runway to a taxiway. It was several minutes after stopping the airplane on the taxiway before the engines were shut down. Following the landing, and prior to initiation of an evacuation, all of the occupants were incapacitated by the smoke and fire inside the airplane. An evacuation was never initiated. All 301 passengers and crew perished in the fire.

Photo copyright Tim Rees - used with permission

History of Flight

On August 19, 1980, a Saudi Arabian Airlines L-1011 took off from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia enroute to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Seven minutes after take-off (approximately 24 minutes before the airplane came to a stop back at Riyadh) an aural warning (Alarm A) indicated smoke in the aft (C-3) cargo compartment. Less than one minute after the first alarm, a second aural warning (alarm B) sounded. The cargo compartments on the L-1011 were originally certified as Class D cargo compartments and included two smoke detection alarm systems in each compartment. The flight crew spent 5 minutes 20 seconds confirming the first fire warning before the Captain elected to return to Riyadh. This confirmation included the Flight Engineer entering the passenger cabin to investigate the situation. When he returned to the flight deck, he reported smoke and fire in the cabin. The airport at Riyadh was contacted, and informed that the airplane was returning because of a fire in the cabin and requested that crash, fire, and rescue be alerted.

After turn back to Riyadh, the flight engineer returned to the passenger cabin to assess the extent of the fire. upon return to the flight deck he reported there was just smoke in the aft end of the aircraft. This was approximately 17 minutes before the airplane came to a stop after landing. A flight attendant reported to the flight crew that there was a general panic among the passengers. Fourteen minutes prior to landing at Riyadh, another aural smoke detector warning occurred, and was recorded on the cockpit voice recorder (CVR). Thirteen minutes before the airplane came to a stop, the Captain stated that the throttle of No. 2 engine was stuck, and that he was going to shut the engine down. Also, at 13 minutes before the airplane came to a stop on the taxiway, another flight attendant reported she could not go further aft than doors L2 and R2 because people were fighting in the aisles. Immediately thereafter, another flight attendant came into the flight deck and reported fire in the cabin. At 11 minutes before the airplane came to a stop, the CVR recorded an announcement by the cabin crew to stay calm and to stay seated. Ten minutes before stopping on the taxiway, a flight attendant came forward and advised the crew, "there is too much smoke in the back." The flight attendant repeated instructions to the passengers to stay in their seats to prepare for landing. Three minutes 33 seconds before the airplane came to a stop another aural smoke detector warning was recorded on the CVR.

A flight attendant repeated instructions to the passengers to stay in their seats to prepare for landing. The aircraft did not make an emergency stop but instead taxied off the runway to a taxiway. Two minutes forty seconds after landing, the aircraft came to a stop on the taxiway. After stopping, a witness parked his car just behind and to the left of the aircraft. He observed a fire through the windows on the left side of the cabin between the L3 and L4 doors. He said there was no fire outside the aircraft at that time. He could not see any movement in the cockpit or cabin.

Immediately after stopping, an announcement was made to the tower 'We are shutting down the engines and are now evacuating'.

One and a half minutes after stopping the tower told the aircraft that the tail of the airplane was on fire. The aircraft responded, "Affirmative, we are trying to evacuate now". This was the last transmission received from the aircraft. View the Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 161 Flight Path Animation below:

Three minutes and fifteen seconds after the aircraft stopped the engines were shut down. Smoke rose from the top of the fuselage, followed almost immediately by flames. A witness that parked his car behind the aircraft said that just as the engines were shut down, there was a big puff of white and black smoke emitted from the aircraft belly, just forward of the wings. Firefighting personnel observed within a minute of engine shut down, smoke rising from the top of the fuselage just forward of the No. 2 engine. Flames followed the smoke almost immediately. See Fire Penetration Diagram.

The crash, fire and rescue personnel did not succeed in opening a door (R2) until 26 minutes after the plane came to a stop. Three minutes after R2 was opened, flames were seen progressing forward from the rear section of the cabin. Bodies were found bunched up around unopened exits. The flight deck crewmembers were found still at their duty stations (seated). The evacuation procedure had not been started. The captain, by continuing to operate engines after stopping the aircraft, may have prevented the flight attendants from initiating the evacuation on their own. Further, the environmental control system packs were shut down before the engines were shut down, resulting in loss of any ventilation air introduced within the fuselage. It was not clear to the investigators why there were no apparent attempts to open any of the cabin doors, even though all doors were physically capable of being opened. Residual cabin differential pressure was determined not to have been a factor in preventing doors from being opened. One possible explanation considered by the investigators was that crowding around the doors prevented the cabin crew from opening any doors, or, that passengers and cabin crew had all been incapacitated, and not capable of initiating a door opening and evacuation.

The burn through of the cabin floor structure was localized beneath the 2nd through 6th row of dual seat units forward of door L4.

Post mortem examinations and toxicological findings revealed that the deaths in this accident were due to the inhalation of toxic gases and/or exposure to the effects of the fire, heat, and lack of oxygen. Heavy soot deposits were found in the tracheas of the majority of cases examined. Bodies were found bunched up around unopened exits. Some bodies had no burns, while others were severely charred. The captain and first officer were found in their seats and had sustained charring burns.

Class D Cargo Compartment

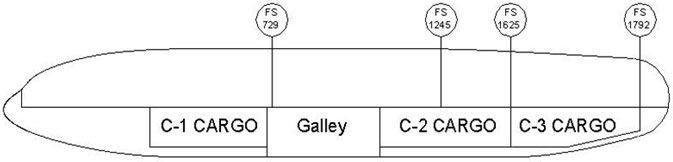

The L-1011 airplane has three lower cargo compartments that were certified as Class D cargo compartments per 14 CFR part, § 25.855.

The forward cargo compartment (C-1) extends from the rear of the Environmental Control Systems (ECS) bay and nose wheel well to the lower lobe galley. The mid cargo compartment (C-2) extends from the main gear wells to Fuselage Station (FS) 1625. The aft cargo compartment (C-3) abuts the C-2 cargo compartment and extends aft to FS 1792. For the subject airplane the C-1 and C-2 cargo compartments were designed for palletized or container cargo. The C-3 cargo compartment is used for bulk baggage/cargo and animal transport. Each cargo compartment is heated by a closed loop recirculation system in which compartment air is circulated over bleed air ducts in a low effectiveness heat exchanger. No fresh air was supplied to the C-1 or C-2 cargo compartments. The C-3 cargo compartment is supplied with 165 cubic feet per minute (CFM) of cabin exhaust air (controllable either manually or automatically) to provide cooling and ventilation for animal transport. An additional fixed flow of 10 CFM was supplied to the C-3 cargo compartment.

The primary method of controlling a fire in a Class D cargo compartment involves containment of the fire within the compartment until the available oxygen is consumed and the fire self extinguishes. This is accomplished by restricting the size and ventilation of the compartment. The intent was that any fire occurring therein would quickly use up the available oxygen and self-extinguish, or at least remain at a non-threatening level for the duration of the flight. Class D cargo compartments were required to have fire resistant liners to protect adjacent structure and systems, which also served as a means to limit ventilation of the compartment and to prevent smoke from entering occupied areas of the airplane, like the passenger cabin. Class D cargo compartments were not required to have fire detection systems, such as smoke detectors, to inform the flight crew of the presence of a fire. However, the subject airplane had two smoke detector alarms that would provide an aural warning on the flight deck.

Historical evidence associated with the effectiveness of fire control in Class D cargo showed mixed success. Because Class D compartments are not required to have fire detection systems, the presences of an in-flight fire was generally not discovered until the airplane landed and the cargo compartment door was opened. Typical causes of Class D cargo compartment fires included baggage contacting airplane electrical components such as lights, and items being carried in passenger baggage or mailbags.

The accident airplane had two smoke detector alarm loops that provided an aural warning on the flight deck. The cargo compartment ceiling liner was constructed of 0.030 inch Nomex fabric material. The investigators inspected the remains of the C-3 cargo compartment but were unable to determine the source of the fire that occurred in the cargo compartment.

The FAA conducted a series of tests approximating possible conditions in the C-3 cargo compartment. A 750 cubic foot simulated cargo compartment was used to determine the effects of airflow shut off on a small cargo fire in a compartment similar in volume to the C-3 compartment. The tests indicated that a small cargo fire, such as one started by a match or cigarette, on or in a bag, could easily reach a temperature that would penetrate the L-1011 Nomex liner. They also indicated that a slowly growing fire, in a compartment the size of the C-3 cargo compartment, could burn for a long duration before the oxygen would be reduced enough to cause a major reduction in flaming.

The FAA conducted a series of tests to determine specific design features and materials necessary to safely contain likely fires in Class D cargo compartments. The first test set up and the C-3 cargo compartment were similar and were released to the accident investigation team for their use. The test compartment used was as follows:

- A drop ceiling was installed approximately 12 inches below the roof. The ceiling was constructed of Lockheed Nomex cargo liner fastened to aluminum structure.

- Airflow in the cargo compartment was 130 CFM until smoke detection, at which time it was terminated.

- Airflow above the compartment was 206 CFM, and continued for the entire test.

- A smoke detector of the same type used in the C-3 cargo compartment was installed using the C-3 mounting panel supplied by Lockheed.

- The volume of the compartment was approximately 620 cubic feet.

The test was conducted using a combination of boxes and actual baggage as a fire load. The compartment was approximately 1/3 full. The fire was ignited in a canvas type bag using two packs of matches set off by a spark from an igniter. Airflow in the compartment was shut off when the smoke detector activated. The following are pertinent test results:

- A large amount of smoke was needed for the detector to properly sense the presence of smoke.

- Burn-through of the Nomex liner occurred around the same time as smoke detection, shortly after flame impingement.

- The fire intensity oscillated during the test. High intensity for a minute or so after burn through, then subsiding as oxygen in the compartment was consumed. Then as fresh air entered the compartment through the breach, the fire would gain intensity, thus again consuming the oxygen. This oscillation occurred 3 or 4 times during the test.

- The smoke detector came on at 2 minutes 59 seconds and went out at 5 minutes 44 seconds. It was determined that soot deposits on the lens of the detector caused the warning to cease. Subsequent tests also showed that heating of a detector could cause intermittent alarms.

- Temperature of significant magnitude and duration to penetrate a floor panel, were measured in the area above the ceiling liner.

- The temperature above the liner oscillated during the test with the highest peak being the first one just after burn-through.

- The hole burned through the Nomex liner was very similar in size and nature to that of the one in the C-3 cargo compartment.

- Damage in the compartment was confined to the hole in the liner and baggage directly under the hole.

The Presidency of Civil Aviation, Saudi Arabia, determined the fire initiated in the C-3 cargo compartment for undetermined reasons. The investigation determined that the C-3 cargo compartment on the L-1011, which was certified as a Class D, did not contain the fire within the cargo compartment as intended by the regulations. The regulations intended that the liner material contain the fire within the cargo compartment, and the fire would quickly consume the oxygen (oxygen starvation) within the compartment before the fire had a chance to get out of control. Testing demonstrated that the Nomex cargo liner material was inadequate to contain the fire within the cargo compartment. As a result of the fire burning through the cargo liner, creating a breach into the cabin, additional oxygen was available to feed the fire in the cargo compartment. The fire quickly spread to the passenger cabin, and the burning material produced toxic fumes, including carbon monoxide.

Investigators determined that the captain did not fully utilize his flight deck crew during the emergency. One example of this was the captain's decision to continue to fly the airplane rather than have the copilot fly the airplane, allowing the captain more time to assess the critical conditions occurring during the return to Riyadh. The Operator's Emergency and Abnormal checklist procedures were not adequately indexed for rapid identification. The captain failed to prepare the flight attendants for immediate evacuation upon landing and did not make a maximum performance stop landing, but instead taxied off the runway. The flight deck crew did not immediately shut down the engines when the airplane came to a stop. This may have prevented the flight attendants from initiating an evacuation because the engines were still operating. By the time when the engines were shut down, the airplane occupants may have become incapacitated by the toxic fumes from the fire and/or flash over fire. There was no evidence of an attempt to open the doors from the inside of the aircraft.

The complete text of the findings is available at this link: Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 163 Accident Findings

The complete accident report is available at this link: Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 163 Accident Report

The Presidency of Civil Aviation, Saudi Arabia, made six recommendations regarding the operational practices of the airline. A complete list of recommendations is found in the full accident report. (Saudi Arabian Airlines Aircraft Accident Report).

The recommendations covered a number of subjects:

- Revision of training programs for aircrew, stressing emergencies and command training

- Additional assertiveness training for junior flight crew members

- Crew matching to ensure cockpit experience levels

- Avoid rehiring of flight crew members who have been previously dismissed due to substandard performance

- Review and amend emergency checklists

National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) recommendation A-81-12, Reevaluate the "Class-D" certification of the L-1011 C-3 cargo compartment with a view toward either changing the classification to "C," requiring detection and extinguishing equipment, or changing the compartment liner material to ensure containment of a fire of the types likely in the compartment while in-flight.

NTSB Recommendation A-81-13, Review the certification of all baggage/cargo compartments (over 500 cu. ft.) in the "D" classification to ensure that the intent of 14 CFR 25.857(d) is met.

14 CFR 25.855 describes the basic requirements for transport category airplanes. Specific cargo compartment classifications, including Class C and E (Class D compartments have now been removed), are described in the referenced regulation. Cargo or baggage compartment smoke and fire detection system requirements are described in 14 CFR 25.858. (14 CFR Part 25)

At the time of the accident, Saudi Arabian Airlines did not have a system in place to ensure flight deck experience level or crew makeup relative to aggregate experience levels. The airline had also rehired several flight crewmembers that had been previously terminated due to performance concerns. The flight crew on the subject flight had limited experience on the L-1011, and all three had inconsistent performance records throughout their careers. All three, at various times in their careers, had been either dropped from flight programs or had failed flight performance evaluations. The investigation questioned the flight crew decision making, especially the decision to taxi following landing, rather than stopping on the runway and evacuating immediately. Flight crew records reflected some of the inconsistent decision making of the crew individually and indicate that their collective decisions in this accident may have negatively affected the outcome.

Further, the crash, fire, and rescue (CFR) personnel appeared to be unfamiliar with the L-1011, particularly with how to open the doors from outside the airplane. Once rescue personnel arrived at the airplane after it stopped, 26 minutes elapsed before the first passenger door was opened. The investigators believed all the doors were operable from both inside and outside the airplane, and that the airplane was not pressurized. The investigation criticized apparent deficiencies in training and emergency preparedness of CFR personnel.

The Class D cargo compartment safety strategy was shown to be flawed, and eventually, as a result of the ValuJet DC-9 accident in 1996, the FAA mandated the removal of all Class D compartments on U.S. airplanes.

The Nomex cargo liner was intended to contain a cargo compartment fire, and in combination with the assumed oxygen starvation characteristics of a Class D compartment, would prevent a fire from progressing outside the compartment until the fire self-extinguished. In this accident, the Nomex liner burned through relatively early in the fire progression (at about the same time as fire detection) and failed in its intent to contain the fire.

It was assumed that the "oxygen starvation" safety philosophy of Class D cargo compartments would limit the oxygen available after a fire started in the compartment, resulting in the fire extinguishing itself. Since this design concept should have resulted in the suppression of any fire, no fire warning system was required by the regulations for Class D cargo compartments. Although not required by the regulations at that time, this airplane did have a fire/smoke detection system, which activated multiple times during the accident sequence.

Further, the Nomex liner was supposed to contain the fire for a time period sufficient to use all the available oxygen and starve the fire. However, the liner failed, allowing an inflow of oxygen from the passenger compartment and progression of the fire to the rest of the airplane.

Two previous accidents, a United Airlines DC-8 in Denver, Colorado in July 1961 and a Trans World Airlines Boeing 707 in Rome, Italy in November 1964, indicated that the existing regulations relating to occupant survival and passenger evacuation were not adequate. After these two accidents, the FAA was aware of the need to upgrade the regulations in the emergency evacuation and cabin safety areas and was evaluating regulatory changes when United Airlines Flight 227 crashed in Salt Lake City in 1965. This accident prompted quicker action and led to Amendment 25-15 which changed many cabin safety regulations.

Civil Aeronautics Board Report for United Air Lines, Douglas DC-8, Denver, CO, July 11, 1961.

NTSB Report for Trans World Airlines, Boeing 707, Rome, Italy, November 23, 1964.

Lessons Learned module for United Airlines, Boeing 727, Salt Lake City, Utah, November 11, 1965.

This amendment introduced a new test method to determine flame penetration resistance of cargo compartment liners. This new method for testing cargo compartment liner materials is contained in Appendix F Part III and employs a large oil burner. This amendment made changes to §§ 25.853, 25.855, and 25.857.

Further, 14 CFR 121 was amended to revise § 121.314(a), Amendment 121-253, effective February 17, 1989, requires cargo liners not constructed of glass fiber reinforced resin to be tested to the requirements of 14 CFR 25, appendix F, part III after the effective date of this amendment.

The current version of 14 CFR 121.314 is available at the following link: 14 CFR 121.314

No Airworthiness Directives were issued to address the cargo liner material of the L-1011 aircraft. However, changes to the liner material in future aircraft were mandated by the changes to §§ 25.853, 25.855, 25.857, and 121.314(a), and were retroactively mandated by a revision to 14 CFR 121.314.

Airplane Life Cycle:

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories:

- Cabin Safety / Hazardous Cargo

- Uncontrolled Fire / Smoke

- Crew Resource Management

Groupings:

- Approach and Landing

- Automation

Accident Common Themes:

- Human Error

- Flawed Assumptions

Human Error

- There were several crew errors during the return to Riyadh, and again while landing and stopping the airplane. During the return flight, the captain did not fully utilize the flight crew in dealing with the in-flight fire. He could have had the copilot fly the airplane, thus providing himself more time to understand the criticality of the in-flight fire. As a result of not fully understanding the critical nature of the fire, he did not prepare the flight and cabin crews for an immediate evacuation once on the ground. Further, the flight crew did not don oxygen masks or smoke goggles on the return to Riyadh, nor did they instruct the flight attendants to use oxygen as needed while fighting the fire to avoid smoke inhalation.

- After the airplane touched down at Riyadh, the captain did not immediately stop the airplane on the runway, but instead taxied off the runway before stopping on a taxiway. Once the airplane came to a stop, the captain did not immediately shut down the engines and initiate an evacuation.

Flawed Assumptions

- The basic safety strategy associated with a Class D cargo compartment was that the compartment was sufficiently small, and that any fire would quickly use all the available oxygen in the compartment. Then, starved of oxygen, the fire would go out. While this process was occurring, it was assumed that the Nomex compartment liner would resist the fire and prevent a threat to the rest of the airplane. Neither of these assumptions proved valid. The compartment liner burned through and was breached very early in the fire sequence. Once the breach occurred, air (oxygen) from the passenger cabin flowed into the compartment, allowing the fire to escalate. Both of these basic assumptions relative to the cargo compartment safety strategy proved flawed.

1996 ValuJet Airlines Flight 592, DC-9-32 (chemical O2 generators transported in a Class D cargo compartment)

ValuJet Flight 592 crashed while attempting to return to Miami, Florida after experiencing a loss of control caused by an uncontrolled fire, initiated by the actuation of one or more chemical oxygen generators which were being improperly carried as cargo in the airplane's forward, Class D, cargo compartment.

Accident Lessons Learned Library Module

1988 American Airlines Flight 132 MD-83 (fire in Class D cargo compartment)

American Airlines 132 flight 132 was loaded with a 104- pound fiber drum of undeclared and improperly packaged hazardous materials, including 5 gallons of hydrogen peroxide solution and 25 pounds of a sodium orthosilicate-based mixture. The hazardous materials caused a hydrogen peroxide reaction in the cargo hold and the flight experienced an inflight fire.

1983 Gulf Air Boeing 737 (incendiary device in Class D cargo compartment)

Gulf Air 191 crashed following the detonation of a bomb the baggage compartment and an immediate fire.

The final report for this accident has not been published.

Technical Related Lessons

Cargo compartments not readily accessible to the flight crew require adequate fire detection and suppression. (Threat Category: Cabin Safety/Hazardous Cargo)

- In this accident, a fire started in the C-3 cargo compartment. The fire quickly burned through the Nomex cargo liner and entered into the passenger compartment. The cargo compartment was certified as a Class D cargo compartment, and was equipped with a fire detection system, even though it was not required by the regulations. The fire detection system detected the fire about the same time as the fire burned through the Nomex liner and entered the passenger compartment. The fire burning through the cargo compartment liner allowed oxygen from the passenger compartment to feed the fire in the cargo compartment. This additional source of oxygen defeated the 'oxygen starvation' fire suppression means of the Class D cargo compartment.

Note: Class E cargo compartments do rely on oxygen starvation as the method of fire suppression, similar to Class D cargo compartments, but with several important differences. Class E cargo compartments require a smoke or fire detection system, means to shut off the ventilating airflow to, or within the compartment, and a means to exclude hazardous quantities of smoke, flames, or noxious gases from the flight crew compartment. In addition, regulatory guidance denotes that some cargo airplanes have a recommended smoke procedure in the Airplane Flight Manual to raise the cabin pressure to 25,000 feet or more to limit the available oxygen supply until the airplane can descend to land.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Proper application of pre-evacuation checklists will facilitate passenger/crew safety in escaping the airplane following a survivable accident. (Common Theme: Human Error)

- Once the airplane had landed, the flight crew delayed initiation of an emergency evacuation. The airplane was taxied after landing, and engines were not shut down for three minutes after the airplane had come to a stop. Existence of, and adherence to, an emergency evacuation checklist would have enhanced the crew's ability to properly configure the airplane and rapidly initiate an evacuation that could have saved lives. In this accident, the time delays were never explained, but were cited as a reason for the large number of fatalities.

When an in-flight fire is confirmed, planning for an emergency descent and landing should begin as soon as possible. (Common Theme: Human Error)

- While still in flight, both the cabin crew and flight crew took deliberate steps to confirm the existence and severity of the fire. Once the fire was confirmed, return to Riyadh and landing were expedited. However, once on the ground, a normal stop - rather than an emergency, maximum performance stop - was performed, and the airplane was taxied clear of the active runway. An additional three minutes elapsed until the engines were shut down. The unexplained crew delays in initiating an emergency evacuation were cited by the investigation as having been key factors in the loss of passengers and crew.