Bombardier CL-600-2B19

Photo copyright Stuart Haigh - used with permission

Comair Flight 5191, N431CA

Lexington, Kentucky

August 27, 2006

On August 27, 2006, at approximately 6:06 AM local time, Comair Flight 5191, a Bombardier CL-600-2B19, crashed during takeoff from Lexington's Blue Grass Airport (LEX), Lexington, Kentucky. All 47 passengers and two of the three crew members were killed. The first officer survived, though seriously injured. Lexington's Blue Grass Airport has two runways. One was identified as runway 8/26, designated for "daytime VFR use only," and intended primarily for general aviation operations. The other runway, identified as 4/22, was intended for commercial airline operations. At the time of the accident, runway 8/26 was 3,501 feet long, while runway 4/22 was 7,003 feet long.

Despite being directed by FAA air traffic control to taxi and takeoff from runway 22, the crew of Flight 5191 incorrectly taxied to runway 26 and attempted to takeoff from the shorter runway. Night visual meteorological condition (VMC) prevailed at the time of the accident. Investigators determined that, without sufficient runway length to attain the target rotation speed of 142 kts, Flight 5191 was unable to takeoff. The airplane struck a perimeter fence, trees and terrain at the end of runway 26 where it was destroyed by impact forces and fire.

History of Flight

Photo copyright Klaus Ecker - used with permission

Comair Flight 5191 was a regularly scheduled flight bound for Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), Atlanta, Georgia. The flight was under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 121. Weather conditions at the time of the accident were 8 miles visibility, broken clouds at 5,000 feet, and no precipitation. Sunrise was at 7:03 AM, approximately one hour following the accident. The moon was below the horizon.

The flight crew boarded the airplane and began normal preflight activities at approximately 5:36 AM. At 5:48 the CVR recorded automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information "alpha" which indicated that runway 22 was in use. About one minute later, the first officer told the air traffic controller that he had received the ATIS information. Two minutes later, the controller provided the crew of Flight 5191 departure information for their planned flight to Atlanta. At 5:52 a discussion among the flight crew was recorded on the CVR concerning which pilot would fly the airplane to Atlanta. It was decided that the first officer would be the flying pilot.

View Larger

At 5:56, the captain stated, "Comair standard," which was determined to be part of the taxi briefing, and "Run the checklist at your leisure." At about 5:56, the first officer began the takeoff briefing, which is part of the before-starting-engines checklist. During the briefing he stated, "He said what runway...two four?" to which the captain replied, "It's two two." The first officer continued the takeoff briefing, which included three additional references to runway 22. After briefing that the runway end identifier lights were out, the first officer commented, "...Came in the other night it was like...lights are out all over the place." Investigators believed that what the first officer was referring to was on the previous day during a repositioning flight that landed on runway 22 at about 1:40 AM, the right runway edge lights after the intersection of runway 26 were out at the time.

View Larger

Following the comment regarding the inoperative lighting, the first officer then stated, "Let's take it out and...take...(taxiway) Alpha. Two two's a short taxi." The captain called the takeoff briefing complete at about 5:57. At 5:58 the first officer called for the first two items on the before-starting-engines checklist, to which the captain commented that the before-starting-engine checklist had already been completed. The first officer questioned, "We did?" The first officer then briefed the takeoff decision speed (V1) as 137 kts and the rotation speed (VR) as 142 kts.

Flight data recorder (FDR) data for the accident flight started at about 5:58. FDR data showed that the pilot's heading bug on the multi function display (MFD) had been properly set to 227 degrees, which corresponded to the magnetic heading for runway 22.

At 5:59, the captain stated that the airplane was ready to push back from the gate. FDR data showed that at about 6:00 they started the left and right engines. At 6:02 the first officer notified the controller that the airplane was ready to taxi. The controller then instructed the flight crew to taxi the airplane to runway 22. This instruction at that time authorized the airplane to cross runway 26 (the intersecting runway) without stopping. The first officer responded, "Taxi two two." FDR data showed that the captain began to taxi the airplane at about 6:02. About the same time, a Sky West Flight 6819 departed runway 22, which would have been parallel to their taxi route at that time.

At this point, the captain called for the taxi checklist. Beginning at about 6:03, the first officer stated, "Radar terrain displays" and "Taxi checks complete." At about 6:04 another commercial transport airplane, American Eagle Flight 882, departed runway 22.

From about 6:03 to 6:04, investigators determined that the flight crew engaged in conversation that was not pertinent to the operation of the flight. At about 6:04 the first officer began the before-takeoff checklist and indicated again that the flight would be departing from runway 22.

At about 6:04, the report indicated that the captain stopped the airplane at the hold-short line for runway 26. To get to the hold-short line for runway 22, (their assigned runway) they should have crossed the end of runway 26 and continued on the connecting taxiway. Afterward, the first officer made an announcement over the public address system to welcome the passengers and completed the before-takeoff checklist. At about 6:05, while the airplane was still at the hold-short line for runway 26, the first officer told the controller that, "Comair one twenty one" was ready to depart. Three seconds later the controller responded, "Comair one ninety one...fly runway heading. Cleared for takeoff." At 6:05, the captain began to taxi the airplane across the runway 26 hold short line. CVR recording showed that the captain called for the lineup checklist at the same time. About one second later, Comair Flight 5191 began turning onto runway 26. About 6:05, the first officer called the lineup checklist complete.

At about 6:06, the captain told the first officer, "All yours," and the first officer acknowledged, "My brakes, my controls." FDR data showed that the magnetic heading of the airplane at that time was about 266 degrees, which corresponded to the magnetic heading for runway 26. At that point, the CVR recorded the sound of engines increasing in power. The first officer then stated, "Set thrust please." to which the captain responded, "Thrust set." Shortly after this response from the captain, the first officer stated, "(that) is weird with no lights," and the captain responded, "Yeah," two seconds later.

Approximately eight seconds later, the captain called, "One hundred knots," to which the first officer replied, "Checks." Approximately seven seconds later the captain called, "V-one, rotate," and then stated, "Whoa!" Investigators determined that the callout for V1 was six knots early, and the callout for VR was 11 knots early. It was also believed that the captain may have been reacting to seeing the end of the runway rapidly approaching.

The airplane impacted an earthen berm 265 feet beyond the end of runway 26, became temporarily airborne, then struck trees and burst into flames. Maximum airspeed recorded was 137 knots. The FDR ended at 6:06:36.

View Comair Flight 5191 Accident Animation below:

Blue Grass Airport Construction

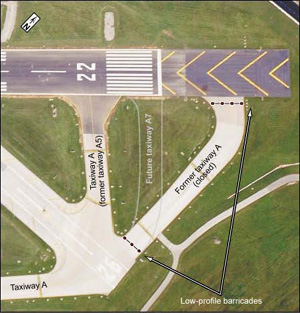

At the time of the accident, LEX was nearing the completion of a multiyear construction project. The project included shifting runway 4/22 325 feet to the southwest to accommodate a longer runway safety area at the approach end of runway 22, relabeling the existing taxiway connectors, demolishing taxiway A5 and taxiway A north of runway 8/26, and creating a new taxiway (labeled A7) at the end of runway 22.

From August 18 - 20, 2006, LEX was closed to resurface and paint new markings on runway 4/22 and change taxiway connector signage. On August 20, the airport was reopened, and a local NOTAM was issued to announce the closure of taxiway A north of runway 8/26. Additionally low-profile barricades with flashing red lights were placed on that part of the taxiway. Former taxiway A5 was re-designated as taxiway A, and was used by airplanes to access runway 22 before the construction of the new taxiway A7, which was planned to be completed about 30 to 45 days after the completion date of the repaving project.

CL-600 Flight Deck Display Layout

The Bombardier Cl-600-100 flight deck is equipped with an electronic flight information system (EFIS) which contains six flat-panel display units. The captain's and first officer's stations each contain multifunction display (MFD) and primary flight display positions. The MFDs are located inboard of the PFDs. The panels between the captain's and first officer's stations contain the engine indicating and crew alerting system (EICAS) displays.

Investigators determined that the flight crew had selected the proper runway magnetic heading selection, or "bug", on the MFD for runway 22 at the time of preflight preparation. This "heading bug" is intended to provide an additional cue to proper runway selection and should have been checked as part of the pre-take off check list procedure.

Airport Signage, Markings, and Lighting

to accomplish airport navigation (Airbus A380 pictured).

This photo shows directions to runway 16 and 14

via taxiway E at this airport.

Photo copyright Gerardo Dominguez - used with permission

The convention for runway identification utilizes the approximate magnetic heading of the subject runway. At Lexington, for example, runway 22 is aligned to an actual magnetic heading of 225 degrees (approximately 220 degrees). Aeronautical charts will depict the actual runway heading in order to properly verify the airplane's heading on takeoff or landing. If using the same runway, but in the opposite direction, the runway designation will be the reciprocal heading. At Lexington, the reciprocal runway is runway 04 (runway heading of 045 degrees).

Airport signage, lights, and markings play critical roles in the confirmation and repetition of position acknowledgement for pilots in determining their location on the airport, complying with mandatory instructions from the air traffic controllers, and utilizing available cues to prevent runway incursions and wrong runway takeoffs. All pilots are vulnerable to loss of situational awareness and surface navigational errors. Even when navigation tasks are straightforward, there is potential for catastrophic outcome resulting from human error if available cues are not observed and considered, especially at night during taxi, and if the airplane's position is not cross-checked at the intended runway.

and taxiway E6 identification

Photo copyright Gerardo Dominguez - used with permission

Despite being instructed to taxi to, hold-short, and takeoff from runway 22 at Lexington's Blue Grass Airport, Comair 5191 lined up on the wrong runway and began takeoff roll. The NTSB determined that the signage, lighting, and markings were correctly displayed on the day of the accident, and that the pilots violated 14 CFR 121.542, the sterile cockpit rule. That rule is specifically designed to ensure that the pilots' attention is directed to operational concerns during critical phases of flight, including taxiing to assigned runways. Had the pilots recognized their location when they reached the hold-short line of runway 26, they would have realized that they had not arrived at the hold-short line of runway 22, the point to which they had been cleared by the ground controller. The NTSB found that the 50-second timeframe during which the airplane was stopped at the runway 26 hold-short line prior to takeoff roll should have provided the flight crew with ample time to look outside the cockpit and see the runway 26 holding position sign, the 26 painted runway number, the taxiway A (alpha) lights across runway 26, and the runway 22 holding position sign in the distance. Additionally, runway 26 was painted with a 75-foot width, narrower than the 150-foot width of runway 22.

The taxi routing and associated cues available to the accident pilots were identical to those that were available to the pilots of the two regional jets (Skywest Flight 6819 and American Eagle Flight 882) that departed minutes before Comair 5191. The Skywest and American Eagle pilots had no difficulty identifying and successfully navigating to runway 22, even with differences in taxiway signage and chart labeling that were discovered in the investigation. In addition, even though the airport configuration at the time of the accident had been in place for only one week, the NTSB did not identify any reports about surface navigation problems during that time. The safety board concluded that adequate cues existed on the airport surface and available resources were present in the cockpit to allow the flight crew to successfully navigate from the air carrier ramp to the runway 22 threshold.

At Lexington, taxiway A, denoted by a yellow solid centerline, blue perimeter edge lights and a black sign with yellow letter A on the right side of the sign, should have led to the presence of runway 22 markings, a white centerline and side stripes, ahead of the airplane. That could have confirmed or denied the crew's perception that the airplane was at the hold-short line of runway 22 instead of actually being at the hold-short line for runway 26. The taxiway A centerline additionally split into three lines after the runway 26 hold-short line, each of those lines leading to a particular point on the airport surface. The center taxiway line led to runway 22, while a right one led to a closed portion of taxiway A and another left line led to runway 26, indicating that a crew would be prior to runway 22.

Takeoff Performance

Adequate runway length determination for transport category airplanes such as the CL-600 involves establishing "decision speeds" which provide for safe accelerate/stop and accelerate/go points on the runway for each takeoff. Airplane performance is evaluated during the certification programs of each airplane type, and V1/ VR /V2 speeds are determined for a range of airplane weights and airport atmospheric conditions. V1 (decision speed) is the maximum speed from which the airplane can be safety stopped on a balanced field using available braking. Failures, such as an engine failure which occurs prior to attaining V1, would cause a flight crew to reject the takeoff and bring the airplane to a safe stop. A balanced field is one where the accelerate-stop and accelerate-go (takeoff and climb to 35 feet) distances are equal. If the takeoff is field length limited, the accelerate-stop distance equals the available runway length.

Failures which occur following V1 should generally not result in a decision to stop since available runway length may be insufficient to safely stop the airplane using available braking. VR, or the speed at which the plane is to be rotated, is the speed at which the flying pilot rotates the airplane to a positive pitch attitude in order for the airplane to become airborne and establish an initial climb angle and safely fly away from the airport. V2 is the safe engine-out takeoff climb speed following lift off. With all engines operating, most takeoff procedures call for the pilot to climb at V2 + 10 kts.

View Lexington Takeoff 101 Animation below:

For Comair Flight 5191, V1 on the day of the accident was determined by investigators to be 135 kts, and VR to be 142 kts. Investigators also determined that V1 for the CL-600 would have required 3,593 feet of runway to attain this speed, and to reach a speed of VR would have required 3,744 feet. Since runway 26 was only 3,501 feet long, attaining a safe takeoff rotation speed of 142 kts would have been impossible.

Post Flight 5191 Accident "Wrong Runway" Study

Shortly after the accident involving Comair Flight 5191, the FAA conducted a review of events involving airplanes departing from or taxiing into position on a wrong runway. A period from 1981 to 2006 identified 80 events involving reported wrong runway operations. The review also identified certain specific U.S. airports which had multiple occurrences of wrong runway events. This study is documented in the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST) report titled "Wrong Runway Departures," dated August 2007.

Several common elements or contributing factors related to airport layout were identified in this study. Risk reduction opportunities were also identified. Common contributing factors observed at these specific airports were:

- Multiple runway thresholds located in close proximity to one another.

- A short distance between the airport terminal and the runway.

- A complex airport design.

- The use of a runway as a taxiway.

- A single runway that uses intersection departures.

Click here to view the complete CAST report, including conclusions and recommendations.

The NTSB issued 28 findings as a result of the accident. The findings ranged from flight crew qualifications to flight crew performance, air traffic controller performance, and runway marking requirements. The complete text of the findings is available at the following link: NTSB Findings

The NTSB determined the probable cause to be:

"The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the flight crewmembers' failure to use available cues and aids to identify the airplane's location on the airport surface during taxi and their failure to cross-check and verify that the airplane was on the correct runway before takeoff. Contributing to the accident were the flight crew's nonpertinent conversation during taxi, which resulted in a loss of positional awareness, and the Federal Aviation Administration's failure to require that all runway crossings be authorized only by specific air traffic control clearances."

The NTSB accident report is available at the following link: NTSB Report

The NTSB issued a number of new recommendations, as well as reiterating previous recommendations, resulting both from this accident and from other events investigated by the NTSB. Also, three previous recommendations were classified in this report. The complete text of the recommendations is available at the following link: NTSB Recommendations

Certification regulations:

14 CFR 25.105 Takeoff

14 CFR 25.107 Takeoff speeds

14 CFR 25.113 Takeoff distance and takeoff run

Operational regulations:

14 CFR 91.129 Operations in Class D airspace

14 CFR 121.135 Manual requirements

14 CFR 121.542 Flight crewmember duties

Airport regulations:

14 CFR 139.311 Marking, signs, and lighting.

14 CFR 139.339 Airport condition reporting.

14 CFR 139.341 Identifying, marking, and lighting construction and other unserviceable areas.

Air Traffic Regulations:

Relative to this accident, the primary air traffic control functions are governed by FAA Order 7110.65.

Over the history of commercial aviation, airports that have existed for decades have been expanded and reconstructed to accommodate advances in technology and increases in commercial traffic. This has led to certain factors becoming prevalent that in some cases have inadvertently affected a flight crew's ability to taxi to and depart on the correct runway. In the event that a flight crew loses positional awareness on the airport, these factors can influence navigation on the airport and may lead to arrival at an unintended runway.

Following this accident, an industry study led by the FAA determined that there were a number of key factors influencing the likelihood of an airplane departing from or taxiing into position on the wrong runway. At Lexington airport, some of these influences were present. A runway crossing was required in order to reach the correct takeoff runway. Further, the two runways intersected, and the runway thresholds were in close proximity to one another. The investigation concluded that runway signage, markings, and lighting were adequate to have allowed the flight crew to determine their position on the airport.

In August 2007, the Commercial Aviation Safety Team issued a report on wrong runway departures and cited the factors contributing to the events. This report is available via a link at the end of the Accident Overview section of this library module.

- The flight crew lost situational and positional awareness and attempted a takeoff on a runway that was too short to accommodate airplane performance requirements.

- Airport signage would be viewed by the flight crew and used effectively in navigating to the proper runway.

- Associated pre-takeoff and takeoff checklists would be properly performed.

- Non-pertinent conversation would not occur during high workload "sterile cockpit" periods during a flight.

- Takeoffs will not be attempted on a runway designated as unusable and with no lighting.

Between 1981 and 2006 there were 117 events involving airplanes departing from or taxiing into position on the wrong runway. Following the Lexington accident, the FAA conducted a study and determined that wrong runway events occurred at many airports and under varying circumstances; however, they occurred most frequently at four airports: Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, Houston Hobby Airport, Salt Lake City International Airport, and Miami International Airport. These airports share the following common elements or contributing factors:

- Multiple runway thresholds located in close proximity to one another.

- A short distance between the airport terminal and the runway.

- A complex airport design.

- The use of a runway as a taxiway.

- A single runway that uses intersection departures.

Three of these factors existed at Lexington airport, in addition to changed runway markings and taxi procedures resulting from ongoing construction that partially reconfigured a taxiway and a runway.

The report of the FAA study is available via a link at the end of the Accident Overview section of this library module.

Enhanced Airport Markings:

Prior to this accident, the FAA had initiated a decade-long effort that was designed to review and improve airport markings, signs and lighting. The FAA's ongoing planned effort was to look for ways to enhance ground navigation at airports. In 2002, the FAA sponsored a Mitre study to determine whether enhanced paint markings would improve the situational awareness of pilots operating on an airfield. The study confirmed that enhanced taxiway centerline markings and surface painted holding position signs were effective in increasing runway awareness among pilots.

These enhanced markings involve three general areas of improvement:

- Extended runway holding position markings

- Required by June 30, 2008

- Enhanced taxiway centerline markings

- Phased requirements between June 30, 2008, and December 31, 2010, based on airport usage

- Surface painted hold signs

- Required by December 31, 2010

On September 29, 2010, the FAA issued Advisory Circular 150/5340-40E, providing information relative to these improvements.

Air Traffic Control:

14 CFR part 91.129(i) was amended to require that all runway crossings be authorized only by specific air traffic control clearance, and to ensure that pilots and personnel assigned to move aircraft receive adequate notice of the change.

FAA Order 7110.65, Air Traffic Control, was also changed in 2010 to prohibit controllers from issuing multiple runway crossings, with an exception for closely spaced runways with centerlines of less than 1,000 feet. Additionally, the order required standard International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) phraseology for airport surface operations and required that ATC personnel speak at reasonable rates when communicating with all flight crews. As a result, "Line up and wait" has been incorporated to replace "Position and Hold" and an aircraft or vehicle must have crossed the previous runway before another runway crossing clearance is issued. This order is in excess of 600 pages and is not included here due to size constraints.

An InFO, Information for Operators, (InFO 07005) was published by the FAA in 2007. The InFO announced new ATC procedures and phraseology to improve runway safety. It became effective on February 5, 2007, and recommended pertinent safe practices for pilots.

The FAA issued InFO 07009 that enforced the safety aspects of prohibiting night takeoffs on runways that are not lighted or are closed. It became effective on May 11, 2007.

On March 16, 2007, the FAA Inspector General's Office issued report AV-2007-038, which presented the results of a study conducted to address tower facility staffing issues identified during the investigation of this accident. The report made a number of recommendations relative to tower staffing. The FAA adopted many of the recommendations and revised N JO 7210.639 in order to bring those recommendations into effect. The revised order defined new criteria for the consolidation of control tower and approach control functions, It also resulted in all FAA terminal facilities that provide approach control and control tower services having at least two controllers assigned to it whenever both functions are opened.

N JO 7110.468 was changed to revise takeoff clearances to include the runway number.

Flight Crew/Operational Procedures:

On September 1, 2006, the FAA issued SAFO 06013, which provided techniques, procedures and items for consideration in training programs that emphasize safe operations in the pre-takeoff and takeoff phases of flight. It also reemphasized that crews maintain the highest levels of airmanship discipline and crew resource management practices during critical phases of flight such as takeoff and landing. Additionally, on April 16, 2007, the FAA issued SAFO 07003 emphasizing the importance of implementing standard operating procedures and training to ensure that an airplane is at the desired takeoff runway.

Airplane Life Cycle:

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories:

- Crew Resource Management

- Landing / Takeoff Excursions

- Midair / Ground Incursions

Groupings:

- Loss of Control

Accident Common Themes:

- Organizational Lapses

- Human Error

Organizational Lapses

At the time of the accident, the control tower at Lexington was staffed by a single controller, performing multiple functions. The investigation determined that after clearing the accident flight for takeoff, the controller initiated other activities, and did not monitor the takeoff. As a result, he did not observe that the flight was on the incorrect runway. The investigation concluded that if the controller had been monitoring the flight, he may have observed that the incorrect runway was being used and stopped the flight before beginning takeoff roll. Following the accident, the FAA revised tower operating procedures at airports that provide both tower and approach control functions, requiring that at least two controllers be on duty.

Human Error

To initiate the accident sequence, the flight crew taxied to, and attempted to takeoff on the incorrect runway - A runway that was too short to accommodate the performance requirements of the airplane. The investigation concluded that during taxi, the crew did not observe proper cockpit protocol relative to "sterile cockpit" procedures and did not appropriately apply crew resource management practices. The NTSB stated that the non-pertinent flight crew conversations during taxi may have led to a loss of positional awareness on the airport and resulted in use of the incorrect runway.

Korean Airlines Flight 084 and Southcentral Air Flight 59

At 1406 Yukon standard time, on December 23, 1983, Korean Air Lines Flight 084, a scheduled cargo flight from Anchorage, Alaska, to Los Angeles, California, collided head-or with Southcentral Air Flight 59, a scheduled commuter flight from Anchorage to Kenai, Alaska, on runway 6L-24R at Anchorage International Airport. Both flights had filed instrument flight rules flight plans, and instrument meteorological conditions prevailed at the time of the accident. The Southcentral Air Piper PA-31-350 was destroyed by the collision impact, and the Korean Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 was destroyed by impact and post-impact fire. Of the eight passengers aboard Flight 59, three were slightly injured. The pilot was not injured. The three crewmembers on Flight 084 sustained serious injuries.

Singapore Airlines Flight 006 Accident

On October 31, 2000, Singapore Airlines flight 006, a Boeing 747, crashed during an attempted takeoff from a partially closed runway at Chiang Kai-Shek International Airport, Taoyuan, Taiwan. 136 of the 179 occupants aboard the airplane, 83 were killed. The report by Taiwan's Aviation Safety Council found that the pilots did not adequately review the taxi route to ensure that they understood that the route to runway 5L (the correct departure runway) required passing runway 5R (a parallel runway that was under construction and open only for taxi operations).

The report also stated that the pilots did not verify the airplane's position with the taxi route as they were turning onto the runway and that the company's operations manual did not include a procedure to confirm an airplane's position on the active runway before initiating takeoff. The report concluded that the flight crew lost situational awareness and took off from the wrong runway despite numerous available cues that provided information about the airplane's position on the airport.137 The Aviation Safety Council recommended that Singapore Airlines "include in all company pre-takeoff checklists an item formally requiring positive visual identification and confirmation of the correct takeoff runway."

China Airlines Flight 011 Incident

On January 25, 2002, China Airlines flight 011, an Airbus A340, departed from a taxiway at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, Anchorage, Alaska, instead of the assigned runway. The available distance on the taxiway was 6,800 feet, but the airplane's calculated takeoff distance was 7,746 feet. The airplane took off, but its main landing gear left impressions in a snow berm at the end of the taxiway. The airplane proceeded to its destination and landed without further incident.

The Safety Board determined that the probable cause of this incident was the captain's selection of a taxiway instead of a runway for takeoff and the flight crew's inadequate coordination of the departure, which resulted in a departure from a taxiway. The Board determined that a contributing factor to the incident was the lack of an operator requirement for the flight crew to verbalize and verify the runway in use before takeoff.138 As a result of this incident, China Airlines modified its Airbus A340 operating manual to include verbalization and verification of the runway in use.

Alaska Airlines Flight 61 Incident

On October 30, 2006, Alaska Airlines flight 61, a Boeing 737, took off from runway 34R instead of runway 34C (center), which was the assigned runway, at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA), Seattle, Washington. The airplane continued uneventfully to its destination of Juneau International Airport, Juneau, Alaska. According to the captain of the flight, the ATIS that was current at the time indicated that departing aircraft were taking off either with the full length of runway 34R or at the point where the runway intersected taxiway Q. The first officer of the flight stated that the takeoff briefing included a departure from runway 34R.

The captain stated that the controller instructed the flight crew to follow a Boeing 757 to runway 34R and that the 757 departed from runway 34R where the runway intersected taxiway Q. The captain also stated that the controller instructed the crew to taxi the airplane into position and hold on runway 34C. Further, even though he repeated this information to the controller, the captain was still thinking that the airplane would be taking off from runway 34R. During this time, the first officer was completing flight paperwork and conducting other preflight activities. After receiving takeoff clearance from runway 34C from the controller, the captain stated that he lined up the airplane on runway 34R and transferred control of the airplane to the first officer.

The airplane departed uneventfully from runway 34R. According to the controller, he was scanning the runways and noticed that the airplane was rolling on runway 34R abeam the tower instead of runway 34C. Because there were no potential air traffic conflicts at the time, the controller thought that it would be safer to let the airplane depart from runway 34R than to have the pilots abort the takeoff. After the airplane had taken off, the controller informed the flight crew that the airplane had departed from the wrong runway.

United Airlines Flight 1404 Incident

On April 18, 2007, about 0625, United Airlines flight 1404, an Airbus A320, taxied onto a closed runway at Miami International Airport (MIA), Miami, Florida, and began its takeoff roll. Night VMC prevailed at the time. A NOTAM indicated that runway 9/27 was closed from 2300 on April 17 to 1000 on April 18; the NOTAM was included in the flight release paperwork. The runway closure was also included in the ATIS information broadcast. The flight crewmembers reported that they had the airport charts out and available. The controller told the flight crew to taxi the airplane to runway 30. The captain stated that he observed taxiway S almost directly opposite from the airplane's position and chose to make a left turn from taxiway S onto taxiway Q.

This parallel taxi route placed the airplane adjacent to runway 30, the assigned runway for takeoff. The captain stated that, as the airplane passed the intersection with taxiway T, he verified that the runway sign was for runway 30. The first officer stated that, during this time, he was busy with flight paperwork and was accomplishing flight control checks. Taxiway Q made a slight bend to the left after the intersection with taxiway T so that the taxiway was parallel with runway 27. The captain stated that he saw a runway, which he believed to be runway 30, when he looked to the right. The first officer called the tower and advised that the airplane was ready to depart on runway 30. The controller cleared the airplane for takeoff from runway 30 while the airplane was still on taxiway Q. The first officer acknowledged the clearance for takeoff but did not state the runway number for the departure. The captain stated that, as the airplane neared the end of taxiway Q, he observed the hold short line and that, because the airplane was cleared for takeoff, he chose to turn directly onto the runway without stopping and transfer control of the airplane to the first officer.

The first officer stated that his heading display was rotating to the right and in the correct direction to line up with the runway, which was still located to the right. The first officer stated that he advanced the throttles, and just before they reached the cruise thrust position, the airplane's nose wheel light illuminated a truck flashing its lights on the right side of the runway. The captain and the first officer stated that they observed the truck at the same time. Simultaneously, the controller was querying the flight crew to determine whether the airplane was on runway 30. The first officer rejected the takeoff, and the captain assumed control of the airplane. Ramp personnel called the tower to advise that an airplane was on a closed runway, and the controller acknowledged this information. The controller subsequently advised the crew to use caution for workers and equipment on runway 27 and instructed the flight crew to taxi the airplane to runway 30.

The airplane then took off to its destination airport-Dulles International Airport, Chantilly, Virginia-without further incident The pilots reported that the runway 27 edge lights were on. However, an airport engineer who witnessed the incident stated that he immediately scanned runway 27 after the event and noted that the runway edge lights were off.

Technical Related Lessons

An airplane that is required to cross intervening runways in order to taxi to the departure runway should be given an ATC clearance that includes identification of all runways to be crossed, in addition to identification of the departure runway. (Threat Category: Midair/Ground Incursions)

- At the time of this accident, taxi clearances provided approval to taxi to a destination on the airport but did not necessarily provide information that specific runways would have to be crossed while en route to the final taxi destination. The taxi clearance for the accident flight was simply to taxi to runway 22. This taxi clearance authorized the flight to taxi across runway 26 while on the way to runway 22 but did not specifically state the crossing clearance. Subsequent to the accident, procedures were changed such that when taxi clearances are also issued, specific crossing clearances are issued, identifying the runway(s) to be crossed en route to the final point on the airport.

Flight crews should positively confirm that airplane heading is consistent with the correct runway heading prior to commencing takeoff (Threat Category: Midair/Ground Incursions)

- Prior to taxiing to the runway, the flight crew aligned their heading indicators such that they would have indicated the runway heading. The flight recorder data indicated that when the airplane was aligned with runway 26, the heading was properly indicated. As such, the investigation team believed that the crew should have recognized that they were aligned with the incorrect runway (the correct indication would have been approximately 225 degrees rather than the approximately 264 degrees that would have been indicated when aligned with the incorrect runway.

Visual monitoring of airplane takeoffs and landings by air traffic personnel can add an additional layer of protection in order to reduce the risks of surface navigation errors. (Threat category: Midair/Ground Incursions)

- At the time of this accident, the air traffic control tower was staffed by a single controller who was performing multiple duties. The investigation established that after issuing the takeoff clearance, the controller did not monitor the accident aircraft, and therefore did not see that it had aligned with, and was attempting a takeoff on, the incorrect runway. While controllers are not required to continuously monitor each takeoff and landing, the NTSB concluded that if the controller had prioritized traffic monitoring above other tasks, the alignment of the accident flight with the incorrect runway might have been noticed and corrected prior to the attempted takeoff.

During high workload phases such as preparation for takeoff, takeoff, preparation for landing, or landing, flight crews should refrain from conversations that are not pertinent to the duties of proper airplane operation. (Threat category: Crew Resource Management)

- The NTSB cited that the flight crew's nonpertinent conversation during taxi resulted in a loss of positional awareness during taxi and led to alignment and an attempted takeoff on an incorrect runway. The NTSB concluded that if the crew had maintained proper cockpit discipline, and followed appropriate crew resource management practices, they would have followed the available airport cues (signage, lighting, and paint markings) and taxied to the correct runway.

A takeoff should not be conducted at night from a runway that does not have runway lights turned on. (Threat category: Takeoff/Landing Excursions)

- At the time of the accident, runway 26 at Lexington did not have runway lighting available and was restricted to day/VFR use only. As such, since it was still night, runway 26 was closed. During takeoff roll, the crew commented on the lack of lighting, and had, prior to beginning takeoff roll, briefed that the runway end indicator lights were inoperative on runway 22, the intended takeoff runway. The investigation concluded that the lack of any runway lights should have indicated to the crew that the aircraft was on the incorrect runway, and takeoff should have been discontinued.

Common Theme Related Lessons

A single controller should not be tasked with providing both approach control and control tower responsibilities for those facilities that incorporate both radar and tower functions. (Common theme: Organizational Lapses)

- At the time of the accident, the tower was staffed with only a single controller who was performing multiple duties. The investigation concluded that the controller did not monitor the progress of the accident flight after he had cleared it for takeoff and did not notice that a takeoff was being attempted on the incorrect runway. Following the accident, the FAA revised tower operating procedures to require that at least two controllers be on duty in towers that provide both control tower and approach control functions. This would have applied to the Lexington tower, where, if the procedure had been in effect at the time of the accident, would have allowed the tower controller more time to monitor takeoffs and landings.