Boeing 737-200

Photo copyright Bob Garrand - used with permission

Air Florida Flight 90, N62AF

Washington, D.C.

January 13, 1982

On January 13, 1982, Air Florida Flight 90, a Boeing Model 737-200 series airplane, crashed shortly after takeoff from Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C. The Boeing Model 737-200 experienced difficulty in climbing immediately following rotation and subsequently stalled. The airplane struck the heavily occupied 14th Street Bridge connecting Arlington, Virginia with the District of Columbia, and then crashed into the ice-covered Potomac River. Seventy of the 74 passengers and four of the five crew aboard were killed along with four occupants of vehicles on the bridge. Loss of control was determined to be due to reduction in aerodynamic lift resulting from ice and snow that had accumulated on the airplane's wings during prolonged ground operation at National Airport. Contributing to the airplane's poor takeoff performance was a significant engine thrust shortfall believed to be due to anomalous engine thrust indications on both engines caused by engine pressure ratio (EPR) Pt2 probes which were believed to have been plugged with snow and ice during ground operation.

Photo copyright Kevin Wachter - used with permission

Air Florida Flight 90, a Boeing Model 737-200 series airplane, was a scheduled flight from Washington, DC to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with an intermediate stop in Tampa.

There were 74 passengers and a crew of four on board. Approximate time of departure for Flight 90 was originally scheduled for 1415 local time. Snow had been falling at the airport all morning and into the afternoon. At 1338 the airport closed all operations for snow removal and was reopened at 1453.

This resulted in Flight 90 being delayed approximately one hour and 45 minutes. During this delay snow continued to fall, accumulating on all aircraft being held, including Flight 90.

During the airport closure, deicing operations were being conducted on all aircraft being prepared for departure, which resulted in a need for flight crews and deicing crews to schedule deicing services in the general sequence of the aircraft being cleared for departure. There were several aircraft cleared for pushback ahead of Flight 90. The flight crew of Flight 90 had communicated their desire for the deicing to begin just prior to the estimated reopening of the airport, being at approximately 1430. Since the opening had been delayed from the original estimated time, deicing that had begun on Flight 90 prior to 1430 was requested to be stopped by the flight crew. Once the airport opening was announced, the flight crew requested the deicing be resumed, which began again at approximately 1450. The snowfall rate was very heavy during the deicing process. At the conclusion of the deicing process, at approximately 1510, the ground crew noticed about two to three inches of snow on the ramp around Flight 90 at Gate 12 where the airplane was parked.

Photos copyright Richard Barsby, Olaf Juergensmeier, Robin Schmitt-Opitz (Rotate), and Vasco Garcia - Used with permission

At 1515, the airplane main entry door was closed and the jetway retracted. At this time an airline station manager, who was on the jetway, was asked by the pilot how much snow was on the aircraft. The manager responded that there was a dusting on the left wing from the engine to the tip and the other areas were clean. At 1525 the tug attempted to push Flight 90 away from the gate. A combination of the slope of the ramp and the snow and slush accumulated around the tires of the tug (not equipped with tire chains) resulted in the tug being unable to move the airplane. At that point the flight crew started the engines and deployed the reversers in an attempt to assist the tug in moving the airplane.

Bottom photo copyright Kazutaka Yagi

- used with permission

Prior to this attempt, the operator of the tug advised the flight crew that use of reversers was against company policy. The operator of the tug was from a contract service provider and not an employee of Air Florida. It is estimated that the engines were in reverse thrust for 30 to 90 seconds, during which a significant amount of snow and ice was observed blowing around the aircraft from the engines.

At approximately 1533, the initial tug was disconnected from Flight 90 and another tug equipped with chains was requested. At this time an assistant station manager for Air Florida, who was inside the terminal between Gates 11 and 12, stated that he saw a small amount of snow on top of the fuselage and radome up to the bottom of the windshield and a light dusting on the left wing. At 1535, Flight 90 was pushed away from the gate and both engines started. The airplane moved into a taxi line up of several other airplanes at approximately 1539.

During the post engine start check list, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded the captain respond "off" to a checklist item "anti-ice." The CVR also recorded several comments between the captain and first officer concerning the subject of ice on the airplane. During this conversation, at 1546, the first officer made a comment, "Well, all we need is the inside of the wings anyway, the wingtips are going to speed up on eighty anyway, they'll shuck all that other stuff." There was then an exchange concerning the amount of ice they were able to observe on their respective wings. The captain commented, "I got a little on mine." The first officer replied, "A little? This one's got about a quarter to half an inch on it all the way."

View Larger

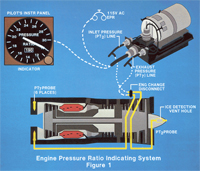

There was also conversation concerning the engine-indication instruments. At 1549, the first officer asked, "See this difference in that left engine and right one?" It was believed by the investigators that the first officer was observing a difference in the EPR being displayed between the left and right engines while the engines were operating at idle thrust. EPR is an indication of engine thrust on the Pratt and Whitney JT8D engines installed on the Boeing Model 737-200, and the difference in the displayed values was believed to be due to one of the engine's inlet probes having been plugged with ice.

The first officer then further commented, "I don't know why that's different-less, 'less it's hot air going into that right one. That must be it--from his exhaust; it was doing that at the chocks awhile ago... Ah."

At 1552, the captain said, "Don't do that-Apple, I need to get the other wing done." It was believed that both the reference to the "hot air going into the engine" and the need to "get the other wing done" was making reference to the hot engine exhaust from the New York Air McDonnell Douglas Model DC-9 airplane that Flight 90 was behind on the taxiway. "Apple" was an air traffic controller term used to identify the New York Air airplane. There appeared to be an expectation by the flight crew of Flight 90 that the ice that had accumulated on the Air Florida Model 737-200's wings would benefit by holding behind the Model DC-9 that was in front of them, and the hot air being ingested by the engines of Flight 90 was influencing the EPR reading.

At 1553, the first officer remarked, "Boy...this is a losing battle here on trying to deice those things. It (gives) you a false feeling of security; that's all it does." The captain and first officer continued a general discussion of deicing until 1554. At 1558, the New York Air Model DC-9 was cleared for takeoff, and the flight crew of Flight 90 completed the pre-takeoff checklist. The CVR recorded verification that the takeoff EPR target thrust setting was 2.04 and the V1 (critical engine failure recognition speed), VR (rotation speed), and V2 (minimum safe speed in the second segment of a climb following an engine failure) speeds to be 138 knots (kns), 140 kns and 144 kns, respectively. It was later confirmed that these were the appropriate takeoff thrust and speed schedules for the Model 737-200, based upon the prevailing airport conditions and the takeoff weight of Flight 90.

At 1559, Flight 90 was cleared to "taxi into position and hold" and to "be ready for an immediate takeoff." At 1559:28, Flight 90 was cleared for takeoff and told not to delay due to landing traffic which was 2 ½ miles out on approach. At 1559:45 Flight 90 turned on to runway 36 and the pilot told the first officer "your throttles." At 1559:56 the CVR recorded the sound of the engines spooling up and the captain saying "real cold, real cold." It was believed by the investigators that the captain may have been referring to the temperature of the engines' exhaust gas temperature (EGT) indications for both engines, since it was later established that the engines were producing significantly less than the target thrust due to the EPR gauges reading erroneously high due to plugged inlet probes. This resulted in the EGT readings being significantly lower than what would normally be expected for takeoff thrust settings. Since the EPR gauges were both set to 2.04 and were apparently indicating 2.04, the crew believed that takeoff thrust was being produced.

(View Air Florida PT2 Probe Animation below)

During the early part of the takeoff roll at 1559:58, the first officer, who was performing the takeoff, commented "God, look at that thing! That don't seem right, does it?" At 1600:05, the first officer again remarked, "...that's not right...," to which the captain responded, "Yes it is, there is eighty." The first officer reiterated, "Naw, I don't think that's right." It was believed by the investigators that the first officer was referring to one or more of the following conditions: (1) the general slow acceleration of the airplane, (2) the lower than normal engine noise, and (3) the position of the engine thrust levers, which would have been significantly less forward than for a normal takeoff using normal takeoff thrust settings. At 1600:20, the first officer commented, "...maybe it is," but then, two seconds later, after the captain called, "Hundred and twenty," the first officer said, "I don't know."

The CVR recorded the voice of the captain calling out V1 followed by V2 six seconds later. The next sound recorded, two seconds after the call out of V2, was the sound of the stick shaker. At 1600:45, the captain said "Forward, forward," and at 1600:48, "We only want five hundred." At 1600:50, the captain continued, "Come on, forward, forward, just barely climb." At 1601, the first officer said "Larry, we're going down, Larry," to which the captain responded, "I know it."

(View Air Florida takeoff animation below)

View Larger

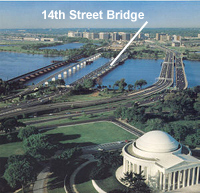

At approximately 1601, Air Florida Flight 90 struck the northbound span of the heavily congested 14th Street Bridge, which connects the District of Columbia with Arlington County, Virginia, and plunged into the ice-covered Potomac River.

The initial impact was near the west end of the bridge, 3/4 mile from the departure end of Runway 36. Heavy snow was continuing to fall and visibility at the airport was between 1/4 mile and 5/8 mile.

Of the 74 passengers and five crewmembers on board, 70 passengers and four crewmembers were killed, including both the captain and first officer. There were also four occupants in vehicles on the bridge killed and several injured.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew's failure to use engine anti-ice during ground operation and takeoff, their decision to take off with snow/ice on the wings, and the captain's failure to reject the takeoff during the early stages when his attention was called to anomalous engine instrument readings. Contributing to the accident were (1) the prolonged ground delay between deicing and the receipt of air traffic control takeoff clearance during which the airplane was exposed to continual snow conditions, (2) the known inherent pitchup characteristics of the Model 737 when the leading edge is contaminated with even small amounts of snow or ice, and (3) the limited experience of the flight crew in jet transport winter operations.

Findings

There were 37 findings listed by the NTSB in the accident report which can be found beginning on page 79. They generally concern the inadequacies of the deicing that was performed on Flight 90 during the time the airport was closed for snow removal; the flight crew's procedural errors while preparing the airplane for takeoff (i.e. use of reverse thrust at the gate, failure to use engine anti-icing, etc.); the delay from the time the airplane was deiced to being cleared for takeoff; the decision to takeoff with knowledge by the flight crew of snow and ice on the airplane's wings; and the decision by the captain to continue the takeoff in spite of several comments by the first officer that something was not right during the takeoff roll. The entire report can be found at: NTSB report.

On January 28, 1982, the NTSB issued ten initial recommendations to the FAA. These recommendations concerned the hazards associated with plugged engine instrument probes, the limitations associated with airframe deicing fluids, revised air traffic control (ATC) procedures concerning inclement weather operations, and the need to emphasize the "clean" airplane concept prior to departure.

These recommendations were followed up with an additional eleven recommendations on August 11, 1982. These additional recommendations, also found in the above cited accident report, involve aspects of ground operation in winter conditions, proper maintenance of ground support equipment, adequacy of winter operation training programs, airplane flight manual anti- and de-ice procedures, airport water rescue capabilities, and additional ATC separation procedures associated with winter operational delays.

The regulations concerning operation in snow and ice conditions relevant to this accident reside primarily within the Boeing Model 737-200 series airplane requirements, the turbine engine requirements, the transport airplane operation requirements, and the airport operation requirements. The ultimate safety of the airplane operation in inclement weather is a result of the combination of these four primary segments working together to provide a design, operation, and facility intended to establish an adequate level of safety. The fundamental contributions of each of these segments includes:

Airplane: the airplane capability for operation in inclement weather is addressed for the turbine inlet system by section 25.1093 ("Induction system icing protection") (14 CFR 25.1093), and the airframe surfaces by section 25.1419 ("Ice protection") (14 CFR 25.1419).

Engine: The basic engine air inlet system operation in inclement weather is addressed by section 33.68 ("Induction system icing") (14 CFR 33.68).

Note: Both the airplane and engine regulations reference section 25C.1 ("Appendix C") (14 CFR 25C.1). This appendix addresses the atmospheric conditions associated with super-cooled water droplets (i.e. icing conditions). For the Model 737-200, ground operation in falling and blowing snow conditions are addressed for the engine inlet system, but not specifically the airframe. section 121.629 ("Operation in icing conditions") (14 CFR 121.629).

Airplane Operation: At the time of the Air Florida Flight 90 accident, it was a requirement that the airplane be dispatched without any snow or ice contamination (i.e. the "Clean Airplane" concept) per section 121.629 (14 CFR 121.629), and that any contamination that accumulated during flight on unprotected surfaces would have been adequately assessed during the part 25 (14 CFR 25) and part 33 (14 CFR 33) certification activities for evaluation of the de-icing and anti-icing equipment of the engine and airplane.

Airport: Snow is expected to be removed and placed in an area that does not pose a hazard to operation per section 139.313 ("Snow removal and positioning") (14 CFR 139.313).

Note: Where possible, the regulatory links cited are the regulations that were in effect at the time of the 737-200 certification. In some cases, the regulation cited is the current version (in effect in 2007) of the applicable rule.

- The flight crew in this accident, though they had undergone training required by their airline, was not experienced in winter operations. It was believed by the accident investigators that the lack of experience in inclement weather operations (winter airport operations) may have contributed to the decisions made by the crew, leading up to the takeoff attempt with ice accumulated on the airplane, and with their failure to recognize the thrust setting error during the takeoff roll.

- There is always pressure to maintain operational schedules, and to avoid conflicts based on schedule variations. On the day of this accident, the airport had been closed for a period of time, disrupting the schedules of the carriers. Upon airport reopening, pressure existed from a number of sources to get airplanes deiced, to expedite departures to relieve traffic congestion at the airport, and to reestablish, as much as possible, the various carrier's schedules throughout the air traffic system that was impacted by the closure.

No key safety issues were specifically identified that directly resulted in airworthiness directives. However, an extensive amount of regulatory and flight manual revisions were issued, as well as several advisory circulars.

The airplane will always be dispatched in a clean (ice-free, uncontaminated ) condition.

The engine instrument probes would not be plugged with ice, or other contamination.

Anomalous engine instrument readings would be noticed by the flight crew, during/immediately, after power set.

Engine and airframe anti-icing would be used whenever required, and be available on the ground, and in flight.

Deicing fluids would be applied appropriately, in accordance with their specifications (concentrations), and at time intervals that maintain their effectiveness.

None.

The crash of Air Florida Flight 90 was a major catalyst for significant advances in the safety of winter weather operations, particularly in the area of airplane deicing technology and procedures. Numerous initiatives were undertaken in order to better understand the properties of deicing materials, techniques for their application, and related training programs. Some of these initiatives were international in nature and required several years to finalize. Major contributions of these efforts include:

Federal Aviation Regulations:

Section 121.629 ("Operation in Icing Conditions") (14 CFR 121.629). Paragraph 14 CFR 121.629(b) was revised to include additional critical parts of the aircraft that frost, ice, or snow could adhere to. Paragraphs 14 CFR 121.629(c) and 14 CFR 121.629(d) were added to provide detailed descriptions regarding dispatch, release, or takeoff of aircraft in conditions that promote frost, ice, or snow accumulation.

FAA Advisory Circulars (AC):

AC 20-117, "Hazards Following Ground Deicing and Ground Operations in Conditions Conducive to Aircraft Icing." This AC was issued immediately following the accident in order to emphasize the "Clean Aircraft" concept. Although a clean aircraft was a requirement at the time of the accident (14 CFR 121.629), this AC highlighted the importance of adhering to the concept and focused attention on the areas particularly sensitive to snow or ice contamination.

AC 120-58, "Pilot Guide: Large Aircraft Ground Deicing." This AC was issued to provide recommendations to flight crews to ensure safe operation of aircraft during icing conditions and developing adequate procedures for deicing aircraft.

AC 120-60, "Ground Deicing and Anti-Icing Program." This AC was issued to standardize the application and training programs associated with ground de-icing and anti-icing programs in support of 14 CFR 121.629.

AC 150/5200-30A, "Airport Winter and Safety Operations." This AC was issued to provide guidance to airport operators on snow removal practices, airplane deicing operations, field condition reporting procedures, and related topics.

AC 150/5300-14, "Design of Airport Deicing Facilities." This AC was issued to provide guidance to airport operators on the features, performance, use, and training associated with airport deicing facilities.

Although there were no airworthiness directives (AD) issued resulting from this accident, it was believed that improvements could be made to many airplane flight manuals (AFM) regarding proper use of engine and airframe ice protection systems. Review of all Boeing models and other large transport airplanes revealed that there was inconsistency regarding the instructions for proper use of ice protection systems for some models. For example, at the time of the Air Florida Flight 90 accident, the Model 737-200 AFM stated:

"Engine Anti-Ice System

...engine inlet anti-ice system shall be on when icing conditions are anticipated during takeoff or initial climb"

In this text, it was unclear as to the proper use of the engine anti-ice system for ground operations. As a result of this potential confusion, all AFMs lacking this clarity were revised to:

"Engine Anti-Ice System

...engine anti-ice system must be on during all ground and flight operations when icing conditions exist or are anticipated...

Icing conditions exist when the OAT on the ground is 50 degrees F or below and visible moisture in any form is present..."

Also, at the time of the Air Florida Flight 90 accident, the Model 737-200 AFM also stated:

"Operation in Icing Conditions.

Do not operate anti-icing systems at high engine power at ambient temperatures above 50 degrees F during takeoff..."

This was changed on the Model 737-200 as well as several other models to provide consistency:

"Operation in Icing Conditions.

...operate the wing anti-ice system as an anti-ice system only during extended operation in moderate to severe icing conditions...as may occur during holding...

...with the engine anti-ice off and a blocked PT2 probe, the indicated EPR will be higher than actual EPR. Crosscheck other thrust indication instruments..."

Airplane Life Cycle:

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories:

- Inclement Weather / Icing

- Crew Resource Management

- Flight Deck Layout / Avionics Confusion

- Lack of System Isolation / Segregation

Groupings:

- Loss of Control

Accident Common Themes:

- Organizational Lapses

- Human Error

- Flawed Assumptions

Organizational Lapses

Air Florida had contracted with another airline for ramp services for deicing and tug operations at Washington National Airport at the time of this accident. It was suspected that placing the engines in reverse thrust at the gate in an attempt to assist the tug in pushing Flight 90 away from the gate may have been contributing to the ice blockage of the inlet pressure probes in the Pratt & Whitney JT8D series engines that later resulted in the thrust shortfall during takeoff as well as contaminating parts of the aircraft surfaces with snow and ice. Prior to attempting this procedure, the tug operator advised the Air Florida flight crew that such operation was against another airlines' policy.

Human Error

Flight crew Errors:

1) The decision to use reverse thrust at the gate. This was not an approved procedure for the Model 737-200 or for Air Florida;

2) The belief that engine exhaust from other taxing aircraft would melt ice on Flight 90;

3) The decision not to use anti-ice on the engines or airframe;

4) The belief that anomalous EPR indications which had been observed during taxi and hold were due to hot gases being ingested into the engines;

5) The belief that ice that had been observed on the wings by both the captain and first officer during taxi would "shuck all that stuff..." during takeoff;

6) The decision to takeoff with knowledge of ice and snow on the wings of the airplane;

7) The decision by the captain to continue the takeoff after several comments questioning the takeoff were made by the first officer during the takeoff roll;

8) The failure to cross-check other engine instruments such as engine exhaust gas temperature (EGT) and high pressure rotor speed (N2) which would indicate a low thrust condition.

Ground Crew Errors:

1) Deicing procedures were accomplished without installation of the engine inlet covers, as required by Air Florida procedures;

2) Deicing of the aircraft was accomplished by another airlines' personnel and were inconsistent with company procedures in terms of method of deicing, concentration of materials, and inspections;

3) The deicing equipment nozzle used on Flight 90 had been changed from the originally installed and calibrated nozzle. This nozzle change resulted in deicing fluid concentrations being delivered to the airplane to be significantly lower than the concentrations that were selected by the controls of the equipment (18% vs. 30%). Although a "mix meter" was available from the manufacturer of the deicing equipment, it had not been installed.

Flawed Assumptions

1) It was assumed that all flight crews would use engine anti-ice protection at conditions such as those that existed at National Airport on January 13, 1982. This was incorrect and was later found to be a source of widespread confusion among many flight crews as to what conditions were intended for requiring systems to be activated. It was believed by many flight crews that engine ice protection systems were intended for in-flight use only, and ground operations, including takeoff, were not operations needing ice protection regardless of the airport conditions. There was also widespread inconsistency in how AFMs described the required use of engine and airframe ice protection system activation, and what constituted "icing conditions;"

2) The engine EPR indication system was configured so that it was assumed that when a Pt2 probe became plugged with ice, the gauge-reading anomaly with the other engine parameters would prompt the flight crew to activate engine ice protection. This proved to be incorrect, especially in circumstances where both engines had plugged probes;

3) It was assumed that the deicing procedures that were being conducted at National Airport were adequate to support the "clean" airframe concept, but the rate of snowfall, the time delay between deicing procedures and takeoff, and the lack of control from the concentration of deice fluids being used combined to allow ice and snow to accumulate on Flight 90.

Air Ontario Flight 1563, Dryden, Ontario, March 10, 1989, Fokker F-28

During an enroute stop at Dryden, Ontario, the airplane was parked with an engine running, as the airplane auxiliary power unit was inoperative, and no ground start cart services were available. Due to the running engine, it was not possible to deice the airplane, and takeoff was initiated with some accumulations of ice on the wings. At the scheduled rotation speed, the pilot rotated, but the airplane would not lift off. The pilot derotated, and continued to accelerate. The airplane, though rotated a second time, never lifted off, and ran off the end of the runway and burst into flames.

See accident module

Scandinavian Airlines Flight 751, Stockholm, Sweden, December 27, 1991, McDonnell-Douglas MD-81

While refueling, clear ice formed on the upper surface of the wings as a result of cold fuel being in contact with the upper surface of the wing forming condensation. The clear ice on the upper surface was not easily detectable by visual inspection, and though deicing took place, the upper surface was not adequately cleaned. During takeoff climb, slabs of ice from the wing broke loose and were ingested by both engines causing compressor damage. The airplane climbed to 3000 feet, but continuing compressor stalls ultimately failed both engines. The airplane crashed into a field, and broke into three pieces, with no fire.

See accident module

Technical Related Lessons:

Even small amounts of frost, ice, or snow can have catastrophic effects on airplane performance. This is especially true for the wings and flight control surfaces (Threat Category: Inclement Weather/Icing)

- The NTSB determined that the takeoff had been conducted with ice still covering portions of the wings. It was known at the time, that wing contamination could affect the lifting properties of a wing, and as a result, it was required that takeoffs not be conducted unless the wings were free of contamination. The "clean airplane" requirement was (and still is) based upon the knowledge that even small amounts of snow or ice could substantially impact an airplane's lift, and therefore its takeoff performance.

Airplane ground deicing and anti-ice procedures should be conducted in a manner consistent with the performance of the materials being used and the inclement weather conditions experienced. (Threat Category: Inclement weather/Icing)

- For the accident airplane, actual de-icing was conducted by another airline, who did not operate any 737 airplanes, and were therefore not familiar with any particular airplane sensitivities or unique features associated with deicing. Further, the investigation discovered that the fluid mixture used in de-ice/anti-ice operations was not correct, resulting in inadequate protection of the wing. The type of material selected, the equipment used, and the weather conditions being encountered all have an influence in the effectiveness of the de-icing process. It is therefore necessary to account for all of these factors in performing the de-icing procedure, and why all winter weather operation programs should contain these details.

Reliance on flight crew recognition of anomalous instrument readings and consistently taking appropriate action is not always reliable. (Threat Category: Flight Deck Layout/Avionics Confusion)

- Engine displays for both of the EPR systems of the JT8D were reading incorrect high readings and resulting in the crew selecting thrust settings too low for a safe takeoff. Since there were no differences between the left and right engines, it was assumed by the crew that the readings were correct, even though the thrust lever angles for both engines would have been much lower than normally experienced.

Environmental conditions, such as snow and ice, have the potential for multiple system effects. (Threat Category: Lack of System Segregation/Isolation)

- Several environmental effects were cited as factors in this accident. Not only were there significant amounts of ice on the lifting surfaces during takeoff, but the EPR system was clogged with ice, resulting in erroneous EPR readings, and a subsequent thrust shortfall. Weather conditions such as icing effect the entire airplane, and often impact multiple systems. It is therefore important to ensure systems are segregated and isolated so that expected malfunctions or expected crew responses, including incorrect responses (delay in recognition, delay in activation, etc.) do not result in a catastrophic outcome.

Flight crew communications regarding airplane safety readiness should be open and effective. Each crewmember must clearly give and receive communication in such a way that the flight safety decisions represent the best product of this open, two-way communication. (Threat Category: Crew Resource Management)

- In this accident, the flying pilot commented several times during the takeoff roll that there was possibly something "not right" about the takeoff. This communication was not effective in the captain stopping the takeoff, and thereby avoiding the accident. This is an example of inappropriate crew resource management.

Common Theme Related Lessons:

AFM instructions should be clear and unambiguous, especially regarding when and how to use safety systems. (Common Theme: Human Error)

- Instructions for the proper use of engine anti ice was unclear in the AFM of the B737, and of many other transport airplanes at the time of this accident. This resulted in widespread inconsistencies in the use of engine anti-ice throughout the industry, particularly how engine anti-ice was being used during ground operations.

Support or contract organizations should perform safety tasks consistent with the appropriate specifications and procedures associated with the equipment being operated, serviced, maintained, or repaired. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapses)

- As stated in another lesson, airplane de-icing was conducted by a contract organization not familiar with the de-icing requirements of the 737. Further, the de-icing fluid mixture appears to have been incorrect, resulting in ice protection that was inadequate for a long ground hold time prior to takeoff. This may have contributed to an accumulation of snow/ice on the lifting surfaces that resulted in a performance deterioration sufficient to cause the crash. Ground services should be consistent with the operators specifications as well as the needs of the specific model airplanes being serviced. This should apply to services being contracted as well as those being accomplished by the airline directly.