Boeing 747-428B

Photo copyright Pima Air Museum Air Nikon Collection

- used with permission

Air France Flight 072, F-GITA

Papeete, French Polynesia

September 13, 1993

Air France Flight 072, a flight from Los Angeles, California to Tahiti was assigned the VOR DME approach to runway 22 at Faa'a International Airport. It was night, and the weather conditions were clear. The airplane was on a stabilized approach in the landing configuration with the auto pilot disconnected, and auto-throttles engaged. At the missed approach point, the automatic flight system initiated a go-around. The pilot of the aircraft physically held the throttles back with his hand, countermanding the automatic flight system, and continued the approach. During landing, the thrust lever for the left outboard engine slipped out of the pilot's hand and commanded by the automatic flight systems, increased to full forward thrust. During the landing rollout, the thrust asymmetry generated with multiple engines in reverse thrust and one engine at forward takeoff thrust caused the airplane to veer to the right and depart the runway on the right-hand side, near the end, coming to rest in a lagoon adjacent to the runway. All passengers were successfully evacuated with only four minor injuries.

Photo copyright Manas Barooah - used with permission

History of Flight/Flight Data

Air France Flight 072, from Paris, France to Tahiti, with an intermediate stop in Los Angeles, California, departed Los Angeles on September 13, 1993. The flight to Tahiti was uneventful. Upon arrival in Tahiti, with the first officer at the controls, the flight began the VOR DME approach to runway 22 (VOR DME 22 Approach Plate) at around 8:40 p.m. local time. It was nighttime and the weather was clear. The airplane was configured for landing and holding a stable approach speed (149 knots) and descent path. The autopilot was not connected, and the auto-throttles were engaged.

At the missed approach point (approximately 500 feet above touchdown), the automatic flight system (AFS) commanded a go-around. The airplane's pitch attitude did not change because the autopilot was not connected, but the throttles were automatically commanded to full-forward thrust.

The investigation concluded that the pilots were unaware of the throttle increase for almost 20 seconds. When they recognized the throttle increase, the first officer, who was flying the airplane, countermanded the throttle/thrust increase by holding the throttles back at idle with his hand. However, the airspeed had already increased to 189 knots and the descent path had leveled off. With the throttles at idle, the airspeed slowly decreased to 168 knots at touchdown, but the airplane landed long, approximately 3,000 feet down the runway and almost 20 knots faster than the recommended approach speed.

Photo copyright tessede - used with permission

This depiction shows the Airplane Runway Trajectory during rollout. An animation of the landing and rollout, culminating in the runway departure, is available below (Landing Excursion Animation). The airplane performance aspects of a long landing are described in the following animation below: (Landing Performance Animation). This animation is also available in the Luxair F-27 Mk 050 accident module elsewhere in this library.

Even though the pilot was restraining all four throttles, the auto-throttle system was attempting to advance all throttles to takeoff power. Two seconds prior to touchdown, the number one throttle slipped from the pilot's hand and advanced to full forward thrust. Neither of the pilots recognized the position of the number one throttle, and at touchdown reverse thrust was initiated on the other three engines. The airplane continued to slow. However, with the number one engine at full forward thrust, the AFS prevented spoiler extension and activation of auto-brakes, which had been armed. This subsequently resulted in delayed actuation of manual brakes. It was not clear if manual spoiler extension was undertaken; however, the spoiler handle was in the DOWN position on the flight deck when examined post-accident by the investigators. The lack of spoilers would affect initial braking effectiveness. The investigation concluded that this, in combination with delayed braking, would have an adverse effect on airplane deceleration. The high forward thrust on the number one engine also caused the airplane to drift to the right, departing the runway and coming to a stop in the adjacent lagoon.

747-400 Thrust Levers (right) – Photo copyright Guillaume Noirot – used with permission

A plot of the engine thrust time history during the landing is available here: Engine Plot

The pilot's were able to shut down engines 2, 3, and 4, but the number one engine did not respond to the pilots commands. The fire department was finally able to get the engine shut down by spraying water into the engine inlet.

View Large

747 Flight Control Automation

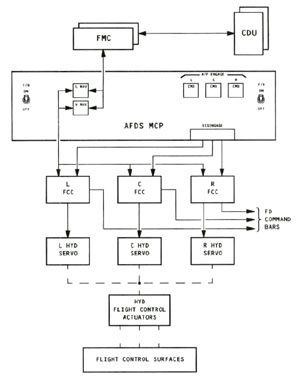

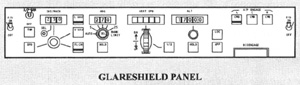

The automatic flight control system on the 747-400 consists of the autopilot flight director system (AFDS) and the auto-throttle system (A/T). The mode control panel (MCP) and flight management computer (FMC) control the AFDS and the auto-throttle system to perform climb, cruise, descent, and approach.

The AFDS consists of three flight control computers (FCC) and the MCP. The MCP provides control of the autopilot, flight director, altitude alert, and auto-throttle systems. The MCP selects and activates AFDS modes, and establishes altitudes, speeds, and climb/descent profiles.

The three FCCs, left, center, and right, control separate hydraulically powered A/P control servos to operate flight controls. The A/P normally controls roll and pitch. Yaw commands are added only during a multi-A/P approach. Nose-wheel steering is also added during rollout from an automatic landing. During an ILS approach with all three autopilots engaged, separate electrical sources power the three flight control computers.

MCP switches select automatic flight control modes. Selected modes are annunciated. The autopilot is engaged by pushing one of the MCP autopilot engage switches. Disengagement is accomplished either through a disengage switch on the control wheel of either pilot, or via the MCP disengage bar. When the autopilot is disengaged, either manually or automatically, a warning message, and aural tone provide an alert to the disengagement.

View Larger

The flight director steering commands normally display any time the related flight director switch is turned on. Autopilot and auto-throttle modes are displayed in flight mode annunciation boxes on the pilot displays.

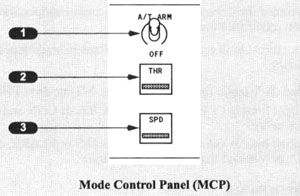

The auto-throttle system can provide thrust control from takeoff through landing. Auto-throttle operation is controlled from the MCP and the flight management computer displays (CDU). The MCP allows mode and speed selection. The CDU allows selection of FMC reference thrust limit. When an autopilot or flight director pitch mode is active, the FMC selects auto-throttle target modes and target thrust values. The auto-throttle can be operated without using the autopilot or flight director.

The auto-throttle can be manually overridden, or disconnected by using either auto-throttle disconnect switch located on the throttles, or by positioning the auto-throttle arm switch to OFF. If either action is taken by the crew, the disconnection is annunciated.

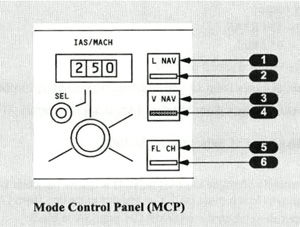

VNAV is an available auto-flight function that computes guidance commands for the autopilot or flight director and auto-throttle to follow the vertical profile of a route, or flight path, programmed into the FMC. VNAV is designed to optimize the airplane's vertical performance capability. A brief overview of the VNAV function, entitled "VNAV for Dummies," is available at the following link: (VNAV Overview).

Air France Flight Profile

In this accident, the copilot was manually flying the airplane with auto-throttles engaged, in good weather. The flight director was active, and the flight guidance mode was VNAV. The flight was cleared for the VOR/DME approach to runway 22.

The early stages of the approach were routine. As the airplane passed through 4,500 feet, the captain read the flight mode annunciator speed and VNAV path instructions. At ten nautical miles from the runway, the landing gear was extended, and the flaps were set at 30 degrees. During this approach, the airplane roll, pitch, and yaw were controlled by the copilot, via the control wheel and rudder pedals, and the auto-throttle was controlling airplane speed by controlling engine thrust levels. The speed commanded for the auto-throttle was the recommended approach speed plus five knots (149 knots). The auto-throttle was employed as a workload reduction strategy, and is commonly used in this manner. The crew monitored the descent path by crosschecking altitude as a function of DME distance, and also monitored the visual approach guidance located near the end of the runway.

All approaches can be categorized as precision or non-precision. The VOR/DME approach in this accident is considered a non-precision approach. At the time of this accident, it was standard procedure for pilots to fly non-precision approaches with the autopilot or flight director engaged in vertical speed mode. The pilots in this accident were using a non-standard configuration by flying the non-precision approach in VNAV versus, for example, the vertical speed mode. In VNAV, the automation is programmed to initiate a go-around at the missed approach point, since VNAV is not an approach mode for the auto-flight system. Though, by initiating the go-around, VNAV in this case performed as designed. Investigators noted that the airplane manufacturer had not made airlines, including Air France, aware of this particular aspect of VNAV. Therefore, Air France had not trained crews to disengage VNAV prior to the missed approach point.

View Larger

At 500 feet the defined "missed approach point", since VNAV was still engaged, a go-around was automatically commanded and engine thrust was increased by the auto-throttles. When VNAV is engaged, the flight path is defined to the point corresponding to a decision height - in this case, the defined missed approach point (MAP) of 500 feet. Once reaching the MAP, if VNAV is still engaged, it is designed to follow the missed approach flight path and initiate a go-around. At the MAP, the approach criteria require that the pilot have sufficient visibility to disconnect the automation and complete the landing. With insufficient visual references, the pilot must perform a go-around. The investigation stated that it was part of the design of the automatic flight system that if an end of descent point is reached (the MAP, in this case), the auto-flight system concludes that insufficient visual references were available, and a go-around is appropriate. When the go-around is initiated, the auto-throttle system increases thrust, and the flight director, if engaged, provides pitch guidance. If the autopilot is engaged, it will fly the airplane through the go-around, maintaining the speed selected on the MCP to the selected altitude.

Aspects of Airplane Design

Crew Training

The airplane automation performed as designed. The investigation concluded, however, that the flight crew did not understand the airplane's response, and reacted inappropriately. The accident report cites several factors that contributed to the accident:

- The absence of information from the manufacturer regarding the VNAV go-around feature of the AFS.

- The crew used a non-standard automation configuration for a non-precision approach.

- The Boeing flight manual recommended that the crew disconnect the autopilot and the auto-throttle before passing the MAP. The accident report stated that Boeing had failed to inform Air France that if the autopilot and auto-throttle were not disconnected by the MAP, the VNAV mode would command a go-around. Subsequently, Air France did not train their pilots to anticipate a go-around at the MAP when conducting a non-precision approach.

As a result of this accident, Boeing modified the automatic flight system logic for non-precision approaches to more closely reflect the VNAV mode performance employed in precision approaches, and made the system upgrade available to the operational fleet.

Autobrakes and Spoilers

The number one throttle moving forward just before touchdown resulted in deactivation of the automatic brakes. The throttle movement also prevented the spoilers from extending automatically. These two events affected the deceleration characteristics of the airplane and increased the deceleration distance (landing roll) of the airplane.

Pilot Procedures

Communication

The accident report cites failure to observe operational procedures regarding call-outs during approach and landing as well as the lack of communication between the pilots, as factors that contributed "greatly" to the accident. The investigation concluded that industry standards and procedures for crew resource management were not followed. The accident report has a detailed list of deviations from these procedures:

- A go-around plan was not included in the approach brief.

- Errors in the checklist were not corrected.

- Several acknowledgements to callouts were missing.

- Following touchdown, the pilot not flying did not make the required call-outs, including the failure of the number one thrust reverser to engage, the deactivation of the autobrakes, or the failure of the spoilers to extend and the pilot flying did not comment, or correct the matter.

Go-Around Standard Procedures

Industry standards dictate that anytime on an approach, whether instrument or visual, when close to the landing, if any parameters of flight become unstable, i.e., altitude and airspeed, a go-around should be initiated. Furthermore, once a go-around is initiated, it should be continued. Once the throttles are advanced, the airplane is committed to going around and is no longer in a safe position to land.

The accident report stated that the pilots did not realize that an automatic go-around had been initiated for almost twenty seconds. Once realizing that they had accelerated above approach speed and the throttles were at go-around thrust, they failed to follow industry standards and aborted the go-around, attempting to land from an approach that had become unstable.

The Psychology of Visual Meteorological Conditions

As a result of this accident, and several other similar accidents and incidents, the French accident investigating body, the BEA, initiated a study of the human factors associated with pilot decision making in visual approach conditions. The study discovered that pilots flying in visual meteorological conditions failed to properly consider going around when an approach was not stable. The report concluded that pilots had the mind set, perhaps unconsciously, that once the runway is visually acquired, there are no further obstacles to landing, and going around is no longer considered as an option. Even when parameters were very unstable, approaches were continued because pilots thought they should be able to make the landing.

In a post accident interview, the pilot of this accident actually described this mentality about weather conditions as an explanation for his decision to continue with the landing.

Photo copyright Philippe Gindrat - used with permission

Federal Aviation Administration Human Factors Team Report on: The Interfaces Between Flight Crews and Modern Fight Deck Systems, dated June 18, 1996

Many accidents, including this one, highlighted difficulties in flight crews interacting with flight deck automation. The FAA, along with U.S. and foreign authorities, manufacturers and operators, launched a study to evaluate the flight crew/flight deck automation interfaces of current generation transport category airplanes. This report is a culmination of that study. The purpose of this study was to identify opportunities for improvements which could be applied in future regulatory and policy development associated with flight crew/flight deck automation interfaces. (FAA report)

Accident Report

The accident report findings concentrate on pilot error, specifically, continuing a non-stabilized approach. The complete findings are available at the following link: (BEA Findings)

Probable Cause

The probable cause of the accident was determined by the BEA to be: The continuation of a non-stabilized approach and go-around thrust application to the number one engine during landing. This resulted from the automatic flight system or automation commanding a go-around at the missed approach point. This resulted in a long touchdown at excessive speed and a trajectory that pulled the airplane right of centerline and subsequently off the right side of the runway.

Failure to observe proper operational procedures regarding callouts during approach and upon landing as well as the lack of communication between the pilots, greatly contributed to the accident. Specifically, deviations from normal parameters (i.e., speed and approach path) should have led to initiation of a go-around.

The absence of information from the manufacturer to operators and crews regarding this particular feature of the automatic flight system was also a contributing factor to the accident.

The complete English language accident report is available here: (Accident Report)

The accident report segmented the recommendations into three categories: Preliminary Recommendations, Intermediate Recommendations, and Other Recommendations.

Preliminary Recommendations are recommendations specifically from the events of this accident and include the following:

- Informing crews of the circumstances of the accident, specifically go-around while in VNAV, and temporarily limit the operational use of auto throttle and automatic modes of the AFDS on standard approaches below approach minimums.

- A call for a study to be conducted regarding the feasibility of supplying power directly from the engines to controls for shut-off valves and extinguishers, and another study about the feasibility of an autonomous battery-run power supply for communication systems between the cockpit and cabin and within the cabin.

- Following an accident on or near a runway, that runway should be closed until rescue operations are complete.

Intermediate Recommendations are recommendations based on this accident and several other accidents with similar circumstances, The BEA had one, as follows:

- Conduct a study regarding the priority of the pilot actions over automatic flight systems be maintained under all circumstances. Which could result in one or both of the following:

- Disconnecting automatic flight systems (autopilot and auto throttle or auto throttle) in cases where pilot actions are in contradiction with those of the automatic flight system or the flight director.

- Providing for a clear message (or possibly an alarm) in the cockpit alerting the crew to such a contradictory situation.

Other Recommendations are also based on this accident, but are not necessarily as critical or causal to the accident as the other two categories of recommendations:

- Crew training in cockpit resource management be used to:

- Improve the effectiveness of reciprocal exchange of information between crew members, including during phases of flight with a heavy workload.

- Encourage crew members to continuously analyze parameters and information linked to how the flight is proceeding so as to make the necessary decisions in a timely manner.

- Unlimited access to pilots' medical records for use in accident investigations should be allowed.

The complete text of the recommendations is available at the following link: (BEA Recommendations)

While there were not any specific regulations that were violated during this accident, the investigation concluded that overall industry standards regarding stabilized approaches and go-around procedures were not followed.

Information regarding the function of the automatic flight control system with VNAV engaged during a non-precision approach was not communicated by Boeing to airlines, including Air France. Consequently, airline training programs did not address AFDS performance with regard to all phases of flight or provide information regarding airplane responses during engagement of VNAV in portions of the envelope where it was not intended to be used.

- The continuation of a non-stabilized approach once a go-around had been initiated by the AFDS.

- Manual override of automatic features rather than disengagement of those features.

- It was assumed the automation would be disconnected before the MAP, while in VNAV mode, if the airplane was in a position to land.

- The flight crew assumed the auto throttles would continue the approach in VNAV mode and completed the landing.

January 9, 1989 - A300-B4 - Helsinki, Poland (Incident)

During an ILS approach with the autopilot (AP) and auto-throttle engaged, the pilot accidentally engaged go-around. To remedy the situation, the pilot disconnected the auto-throttle and pulled back on the thrust levers after four seconds while countermanding the AP by pushing forward on the control column for ten seconds to avoid having passengers undergo a sudden change in attitude. The trimmable stabilizer reached 8° nose-up pitch (the initial approach value was 5.5° nose-up pitch). Subsequently, the AP was disconnected, or disconnected itself without the crew noticing. Then, seeing that the approach had not stabilized, the pilot performed a go-around by selecting the auto-throttle go-around mode. The combined effect of the pitch-up moment of the engines and the nose-up pitch of the trimmable stabilizer took the airplane to an attitude of 35.5°, and 94 kt indicated airspeed in spite of the crew's pushing forward on the control column. Not long before reaching these values, the crew moved the trimmable stabilizer to 0°. The speed increased again while the attitude decreased.

February 14, 1990 - A320-231 - Bangalore, India (Accident)

During a "captain's" inspection flight, the pilot at the controls made a visual approach with the auto-throttle and the flight director active (in mode V Speed: vertical speed holding). On final approach, he requested display and selection of a vertical descent speed of 700 ft/mn on the Flight Control Unit (FCU). For unknown reasons, the pilot not flying, who was an instructor displayed an altitude below that of the airfield on the FCU (instead of the vertical speed requested), and did not make the call-outs required when making a change to the FCU. Subsequent to this action, the active mode of the automatic flight systems went from Speed Vspeed (speed holding-vertical speed) to Idle Open Desc (Open Descent - engine in flight idle- change of level in descent). The pilot at the controls was not aware of this, and the instructor did not call it out clearly. To maintain the descent path visually, the pilot at the controls pulled the control column gradually back, causing the landing angle to increase and the speed to decrease. The anti-stall function led to an increase in the rate of descent, and the alpha floor initiated an automatic go-around. This occurred at too low a level, and the airplane touched the ground and hit a mound. The airplane caught fire, and 92 persons were killed and 22 were seriously injured.

See accident module

February 11, 1991 - A310 D-ADAC - Moscow, Russia

During a go-around procedure in autopilot mode (CMD mode), the pilot tried to limit the pitch-up attitude, which he thought to be excessive, by pushing on the control column (14° nose down). The autopilot then ordered the trim to -12 nose up in an attempt to maintain the specified parameters. On arrival at the safety altitude, the autopilot went into Altitude Acquire mode and disconnected automatically because of the effort on the controls exerted by the pilot (disconnection is inhibited below the safety altitude). The crew then found itself in manual control with a significant pitch-up moment caused by the out-of-trim pitch, to which was added the pitch up moment caused by the engines in go-around power mode. The movement of the elevator control was insufficient to countermand this combined pitch-up and prevent an increase in attitude. The airplane stalled three times in a row, pitching down and recovering at 2.5 g each time. The pilot regained control of the airplane by reducing engine power. The out-of-trim correction phase occurred later.

July 2, 1993 - 747-128A - Air France - Santo Domingo

This incident occurred just three months before the Air France accident. In this incident, the crew failed to stabilize the approach. As a result, the airplane landed very long and at a higher-than-normal speed, overrunning, and stopping just off the end of the runway. The major similarity between this accident and the Tahiti accident was that the VFR weather conditions precluded the flight crews from considering go-around options from a non-stabilized approach. As a result of the Santo Domingo accident, Air France had launched a campaign to heighten crews' awareness of the dangers inherent to non-stabilized approaches.

December 27, 1991 - MD-81 - Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) - Stockholm

The airplane was not properly de-iced before the flight, and shortly after take-off ice from the wing was ingested in the rear-fuselage-mounted engines, causing both of them to fail. The manufacturer had included a common feature that reduced engine thrust during takeoff for noise abatement considerations. However, unbeknownst to the flight crew, the manufacturer had also included a feature that applied full thrust to both engines if an engine failure was detected, during the time frame of reduced thrust. In this case, with a dual-engine failure from ice ingestion, it was inappropriate to increase thrust on the badly damaged engines. The pilots, not realizing what was happening to the engines, failed to reduce thrust manually. The engines could not operate at full thrust with the damage they had sustained and failed due to turbine damage.

See accident module

- There were not any operational regulations or policies that were changed as a result of this accident.

This accident was considered to be the result of operational errors. No Airworthiness Directives were issued.

Airplane Life Cycle:

- Design / Manufacturing

- Operational

Accident Threat Categories:

- Crew Resource Management

- Flight Deck Layout / Avionics Confusion

- Incorrect Piloting Technique

- Landing / Takeoff Excursions

Groupings:

- Approach and Landing

- Automation

- Loss of Control

Accident Common Themes:

- Organizational Lapses

- Human Error

- Flawed Assumptions

Organizational Lapses

It became clear during the investigation that Air France was not aware of the specific features of the VNAV system and its intended behavior during approaches. Nor were they aware that the mode needed to be disengaged at the missed approach point. Though Boeing had provided information related to system usage and recommended practices, specific information about system response if engaged beyond the missed approach point was not clearly provided. As a result, Air France had not provided training to its crews, and the accident crew was not aware that system disengagement was required prior to landing.

Human Error

When the auto-throttles advanced to go-around power, they remained at the go-around position for nearly 20 seconds before the pilot flying manually restrained them, and then retarded them to the idle position. The auto-throttles were never disconnected, requiring the pilot to continue holding them at idle while continuing the landing. If the auto-throttles had been disconnected, thereby cancelling the command to advance to go-around thrust, a successful landing would have been possible.

Flawed Assumptions

The flight crew assumed that it was acceptable to continue a VNAV approach all the way to touchdown. The system was not intended to remain engaged beyond a predetermined point in the approach (missed approach point). As a result, when reaching that predetermined point, the system commanded a go-around.

January 9, 1989 - A300-B4 - Helsinki, Poland

February 14, 1990 - A320-231 - Bangalore, India

See accident module

February 11, 1991 - A310 D-ADAC - Moscow, Russia

December 27, 1991 - MD-81 - Scandinavian Airlines System - Stockholm, Sweden

See accident module

March 22, 1994 - A310-300, F-OGQS - Novokuznetsk, Siberia

April 26, 1994 - A300-600, B1816 - China Airlines - Nagoya, Japan

See accident module

November 12, 1995 - MD-80 - American Airlines - Bradley International Airport, CT

December 20, 1995 - 757 - American Airlines - Cali, Colombia

See accident module

Technical Related Lessons

If manual override of an automatic flight control system becomes necessary, it should be accompanied by an immediate disconnection of the system. (Threat Category: Incorrect Piloting Technique)

- Prior to landing, the autothrottles were engaged, and the AFDS was in VNAV mode, though the autopilot was disconnected. VNAV is not intended as an approach mode, and its associated automatic functions (such as autopilot and auto-throttles) are required to be disengaged at the designated missed approach point in order to proceed with the landing. In this case, when reaching the missed approach point and since VNAV was still an engaged mode, the designed airplane response was to initiate a go-around. When the throttles automatically advanced to go-around thrust, the pilot flying manually restrained the throttles and held them at the idle position. Just before touchdown one of the throttles escaped his grip, and once again advanced to go-around thrust. Further, advancement of the number 1 thrust lever inhibited the activation of the ground spoilers and automatic brakes.

Common Theme Related Lessons

Automatic flight control systems which, when operating as designed can control, or take over control of the airplane, should be fully described by the manufacturer, and fully trained by the operator. (Common Theme: Organizational Lapses)

- VNAV was not intended to be engaged all the way to touchdown. The design was such that once reaching a predetermined altitude on any non-precision approach, the automatic features, and VNAV, would be disengaged, and the airplane would be landed manually. According to the investigators, Boeing had not adequately described the various features of VNAV to airline customers, and as a result, airlines had not provided training to flight crews regarding many aspects of some automated functions. The crew of Air France Flight 072 was not aware that VNAV would initiate a go-around at the missed approach point. When the go-around was automatically initiated, they deviated from normal procedures and manually overrode the system in order to complete the landing. The investigation concluded that if the crew had been aware of the constraints associated with VNAV usage, they would have disengaged the system at an appropriate altitude and successfully completed the landing manually.